What’s the best way to scale marketing?

When marketing grows beyond one person, how do you divide up the work? This is one of the key strategic decisions the CMO makes, as the architecture of the marketing organization shapes its strengths and weaknesses. As my operations professor at MIT often said, “structure dictates behavior.”

The most common way of organizing marketing has been a hybrid of three kinds of divide-and-conquer approaches:

- by product (and overall corporate marketing)

- by tactic, such as advertising, PR, search marketing, the web site, etc.

- by region, usually large ones such as North America, Asia Pacific, etc.

Front-line marketers specialize in a particular product, tactic, and/or region — developing experience and expertise in that area. As the company grows, the size of each of these silos grows, independently of each other.

The challenges, however, are communicating and coordinating among these different groups. Any time you cross an organizational boundary, issues arise with priorities, resources, attribution, costs, metrics, etc. Sometimes these issues are small, sometimes not so small. But they’re always a drag on the organization’s speed and agility — and frequently a source of continuity problems for customers.

After all, customers experience their interactions with you as a continuous flow through their eyes. They don’t care about your organizational structure. They don’t see the dividing lines between, say, the search marketing team and the email marketing team. All they know is when you make sense — when each interaction with you builds upon the previous one for how you will help them specifically — or not.

Unfortunately, far too often, such continuity is woefully lacking.

This problem is exacerbated by the number of new marketing tactics coming into the mix, especially with the explosion of social media marketing and marketing automation tools. There are ever more moving pieces under marketing’s umbrella, but they can end up like a 100-piece orchestra with each instrumentalist in a separate cubicle, only getting cues from the conductor via weekly email memos.

The wonderful divisibility of audience segments

There is another way to divide-and-conquer marketing: by audience segment.

An audience segment is a subset of your customers who are similar to each other and have a shared context in how they buy and use your products or services. Such segmentation might be by industry, or job function, or size of the customer’s organization. Clay Christensen might characterize a segment as what people “hire” your product or service to do — different customers hire you for different reasons, and a cluster with the same reasons is often a good segment.

You can get as granular with segmentation as you want. You can often take a given segment and break it into smaller, more specific subsegments. How far you should subdivide is a function of economics and common sense.

For instance, my company, ion interactive, sells a post-click marketing SaaS. We have a segment of customers who use our product for lead generation. Within that segment, we have a segment of high-tech companies generating leads. Within that segment, we have a further subsegment just for software companies generating leads. And so on.

Two rules with such segmentation:

1. Every time you break out a new segment, you have to dedicate resources to it.

2. The more specific a segment is, the more specific your marketing to it can be — and, accordingly, the better you’ll perform within it.

So you want to segment as much as you can to get the advantage of rule #2, while balancing the constraints of your available resources limited by rule #1.

For most of marketing’s history, the overhead associated with managing a new segment was significant. You still had big silos of tactics and products and regions, and marketers focused on a segment were either restricted within a particular silo (i.e., different advertising to reach different segments) or had to negotiate across the boundaries of multiple silo juggernauts. Since there were very few mechanisms for coordination between silos, this was really painful. Or your segment had to be big enough that it could have its own silos — in which case, I’d argue it was more of a market than a segment.

So as a matter of practicality, most real segment-specific interactions have been left in the hands of the sales department.

“Tiger teams” for audience segments

But the rapid evolution of new marketing — with software driving everything from advertising and search marketing, through to landing pages and website optimization, followed up by marketing automation and email marketing, all tied together by analytics and a CRM — is changing the mechanics and economics of marketing operations.

With the right software and support services, it’s now possible for a very small team — even a single individual — to run a full-lifecycle marketing program for a specific segment. Such a “tiger team” can directly manage everything for a particular segment:

- segment-focused social media marketing

- targeted search marketing and advertising

- targeted landing pages with deep, relevant SEO content

- follow-up marketing automation and email marketing

- personalized hand-offs to appropriate sales channel

- ongoing loyalty and relationship marketing

As long as they have the tools at their disposal (access to PPC advertising management, landing page production, marketing automation, marketing analytics, etc.) and a few key services (most importantly great graphic design) they can produce everything needed to serve their particular subset of customers.

The benefits of this segment team approach include:

- more focus for messaging and engagement with customers, since the segment team is authentically living and breathing the perspective of their narrow audience

- more continuity for customers, since all their touchpoints with the company — search, social, email, web — maintain that targeted perspective in harmony

- more agility as the team managing the segment is small and has end-to-end control over their strategy and production — minimal coordination overhead

- more experimentation as segment teams are encouraged to tailor ideas to their audience and can take risks that are relatively small in scale

- more learning for segment team members, who get visibility to the entire lifecycle of customer marketing from day one, constantly innovating at each point

These segment tiger teams can move fast. They’re entrepreneurial, even if they live within the context of a gigantic enterprise. All of these benefits combine to enable much higher performance.

Can you imagine a more siloed, mass-marketing-style competitor coming up against a laser-focused segment tiger team in the battle to win a specific customer’s heart and mind? The safe money is definitely on the tiger.

The segment-centric marketing organization

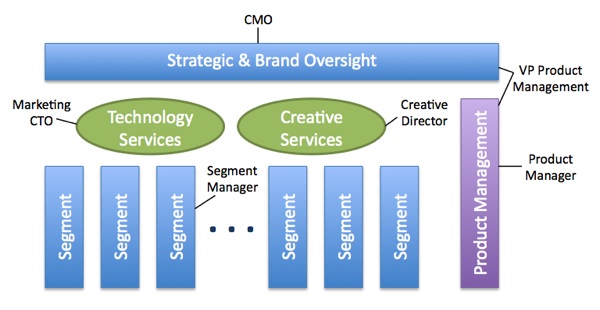

Once you acknowledge the feasibility — and tremendous power — of segment tiger teams, then you can imagine a marketing organization where a multitude of these segment teams thrive together at the very core of marketing. Rather than marketing being primarily defined by tactical silos, it is driven by truly customer-focused segments:

How does such a segment-centric marketing organization scale? As it grows, it subdivides its segments further and further. It can also seek out new niches that would have been impractical for large teams to address, but for which agile segment teams are perfect. This enables even big enterprises to continue to grow organically, as they have an organizational architecture that empowers them to effectively pursue a Long Tail strategy.

In such an organization, segment teams — and customers — are front-and-center. They truly deliver on the promise of integrated marketing for their audience.

The performance metric for segment teams is simple and clear: number of customers acquired — and value of those customers — relative to the cost to win those customers. All other metrics, such as CTR, CPC, social engagement points, conversion rate, fans and followers, etc., are intermediate metrics that a segment team uses to guide its efforts.

Surrounding these segment teams are a set of groups to support them:

- technology services with marketing technologists run by a marketing CTO, who provide the tools and technical glue to help segment marketers execute their ideas

- creative services that provide top-notch graphic design that adheres to common brand standards

- product management that intertwines marketing and product development by synthesizing product needs from across multiple segments

- strategic & brand oversight that provides cohesion to segment-centric marketing — but as a common substrate more than a domineering dictatorship

This strategic layer is responsible for launching new segments, sunsetting old ones, cross-pollinating best practices, and resolving contention between segments. A relatively small team provides necessary corporate marketing that spans all segments — such as a corporate web site and brand standards. It also influences unity among the segment teams via the shared technology services and creative services teams.

But it’s a flat, bottom-up organization, not a top-down one. These other teams are measured by the aggregate performance of all the segment teams they support.

To be sure, there are challenges with this organizational strategy, even while it sidesteps many of the known problems with traditional marketing organizations. But if we want to really take advantage of the new marketing — its new capabilities and dynamics — then we have to do more than incrementally tweak current structures. It’s time to envision a new marketing organization that leverages new marketing as a native.

Hi Scott,

Thanks for this great article. I am a CMO and looking at implementing this team structure at the moment. In this structure, how would you however deal with making sure all the social media, website copy and content marketing are cohesive and the company is not sending out mixed messages, which creates silos and that is exactly what tiger teams need to prevent from happening.

Thanks,

Cornelis

Hi Scott,

Thank you for this really interesting article. Is there any further reading you’d recommend that explores these ideas in more depth?