Today’s Q&A guest is Cesar Brea, author of Marketing and Sales Analytics. Cesar leads Force Five Partners, a marketing analytics consulting firm.

Cesar’s book includes primary research and interviews with more than a dozen major brands across several industries, providing an up-to-date look at what people are actually doing to build their capabilities in this arena.

1. There are no shortage of analytics books in the world. Why did you want to write one?

Lots of what we hear about the explosion of marketing analytics is driven from the vendor side. The clients we work with are, however, “in the arena,” where progress and value are more challenging.

I thought the market would find it useful to hear from some capable people wrangling this reality, both their raw stories and some simple, pragmatic lessons we can distill from them and put to work.

2. What’s surprising about marketing and sales analytics today?

All this data should have made us better at targeting and persuasion. Arguably, what we should have seen therefore is an increase in the sales to marketing and sales expense ratio. But we haven’t — advertising in the US has stayed at roughly historical levels, about 1% of GDP.

It could just be that it’s all an arms race, where any advantages people create get competed away, as agencies and vendors share innovations with others. That would suggest firms are better off doing more in house, at the margin, like making sure they develop and protect proprietary data sources, and do things like programmatic buying in-house, as one specific example.

Firms are better off doing more in house, at the margin, like making sure they develop and protect proprietary data sources.

But if they do, it’s going to be really important that they don’t confuse means for ends. Many marketers come up the ladder as managers of projects, not businesses. A project manager works within a silo or a staff role, and thinks in terms of delivering a fixed scope, on budget and on time. A business manager looks for performance bottlenecks across a customer experience, and works solutions from simplest-possible to more-complex, in short cycles, watching for diminishing returns.

Part of the problem is semantic, which I think reflects this unholy union of vendors with things to sell and marketing managers with things to implement. We use adjectives and nouns to describe what’s happening in marketing analytics, not verbs that describe the use cases and actions that are the objects of the capabilities. For example: “big data” or “propensity models” versus “re-targeting” or “look-alike targeting”. The verbs just naturally beg to be asked, “So, how well?”

The most capable executives out there know that superior marketing is a dynamic enterprise, where edges are temporary, and need to be renewed. Doug Collier, CMO at La-Z-Boy, talks about how “lift-over-control” has become a religion in his organization.

3. Are there metrics myths that many marketers (and salespeople) are falling prey to?

I’m not sure it’s a myth per se, but one of the common patterns we’ve observed is marketers spending lots of time identifying the perfect KPIs, and then spending lots of time on making sure the data for these are as perfectly-defined and clean as possible. In doing so, they fall back into the trap of confusing means for ends. The end isn’t publishing precise reports, it’s continuously working to improve the results of the business.

A better marketer grabs what’s available, knowing that data are at best “platonic shadows” for the reality of the business.

A better marketer grabs what’s available, knowing that data are at best “platonic shadows” for the reality of the business, interpolates across this data, and experiments continuously to see if an insight can be translated to a positive business result. One specific example of this is all the debate about how to define engagement in digital properties. In general, I’ve found it’s more useful to look across a range of stock metrics — return visits, bounce rates, next-page frequency — maybe do some correlation analysis across them to see if some are more predictive of conversions or sales than others, and then start experimenting on moving the winners.

A corollary pattern is, once the KPI sets have been defined, to farm out accountability across a range of people in ways that reinforce silo-ed thinking and local optimization. I think it’s really important that all marketers keep their eyes up across a range of metrics that describe the whole experience, to make sure they’re not doing things that make no sense, like driving lots of unqualified traffic and leads.

Finally, I’ve observed that there’s a tendency to treat models and modeling efforts as black boxes created and managed by experts. Often the folks doing the analysis come — recently — from academic backgrounds and are more concerned with the n-th degree of predictive power, than with speed-to-market, continuous improvement, and actionability and communicability of insights. Where modeling is done well, it’s more of a process than a project, and the marketers can tell you the 4-5 major predictive variables, and how they put those to work.

Often the folks doing the analysis from academic backgrounds are more concerned with the n-th degree of predictive power, than with speed-to-market.

4. What are the challenges in advancing marketing/sales metrics, and how do you overcome them?

There’s that military dictum, attributed I think to von Clausewitz, that says “Amateur soldiers think tactics, professionals think logistics.”

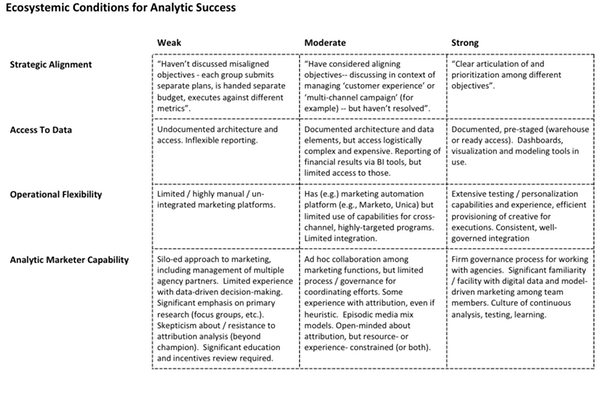

What I’ve seen in this domain is lots of attention to algorithmic sophistication and hiring unicorn data scientists, and less on what we’ve called “ecosystemic conditions”: making sure senior teams are aligned on questions worth asking, ensuring practical access to good-enough data, matching analytic sophistication with the operational flexibility needed to act on it, and cultivating an “analytic marketer” mindset that moves us beyond “right-brain” marketers and “left-brain” analysts lobbying requests and reports back and forth.

Here is a simple diagnostic from the book you can use to figure out where you are:

Our experience — and the dominant pattern among the folks we interviewed for the book — was that you don’t address these through windy, conceptual interventions, but through practice, practice, practice.

You take senior teams through a structured, regular review of where this quarter’s marketing performance bottlenecks are across target segments and their experiences, and you treat your collection of analytic projects relevant to these bottlenecks the way a VC would evaluate a portfolio of investments, with gates for whether insights are being generated, whether experiments based on these insights are being fielded, and whether the winners are being scaled.

You treat your collection of analytic projects relevant to these bottlenecks the way a VC would evaluate a portfolio of investments.

There’s a bias for action in this that’s motivated by behavioral science, but more than that it’s an observation that in the face of what to many seems like a complex thing, momentum is strategic.

Thanks, Cesar!

The end is (continuously) improving the results of the business. That’s a fabulously powerful statement. This seemingly small change in view massively impacts how marketing teams actually interact with the rest of the business and how they deliver.

Sounds like a “growth hacking” mindset (both in people and projects). Look for new patterns in the data, conceive ways to exploit them, test, scale, repeat.