About a month ago, I received an odd comment on my blog, “Martec’s Law was quoted by the Portuguese navy with respect to asymmetrical warfare. It is definitely a law now.”

Huh? That mandated an immediate Google search.

Sure enough, Martec’s Law had just appeared in Jane’s Defense Weekly — what AdAge is to marketers, Jane’s is to defense industry professionals — in the article, Portuguese Navy reveals existence of “tech guerrilla” unit. (Ironically under the section “Air Platforms,” which is a kind of platform I hadn’t really thought about before.)

I was amazed that the concept of Martec’s Law had spread so far that a navy officer was now citing it as part of the inspiration for an innovative new unit they were spearheading, reporting directly to the fleet commander.

And I thought marketing was a high stakes job having to report to the C-suite.

It was also written up on Ars Technica, with the more colorful headline: Portugal’s navy reveals “tech guerrilla” unit creating tech toys that kill. Ars Technica explicitly attributed Martec’s Law as “a proposal by tech executive Scott Brinker.”

“Toys that kill” certainly isn’t what I had in mind when I proposed Martec’s Law, and I admit, I find the association a little discomforting. But I understand the point they were making.

While it is a slow and expensive process to change major military forces in response to the latest technology, new enemies — unencumbered by large, legacy organizations — are free to improvise attacks with any off-the-shelf technology that’s available in stores. These new enemies are disruptors, leveraging cheap, new technology in a highly agile fashion.

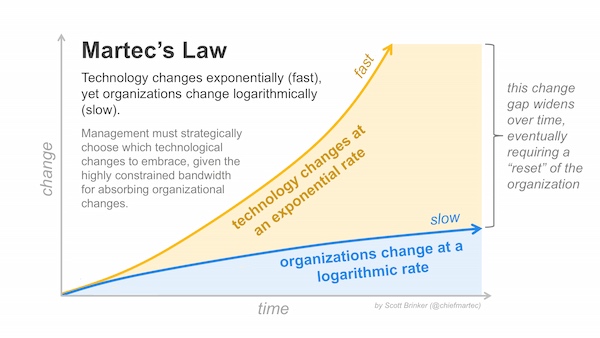

Like new start-up competitors in a business setting, these “new entrants in the market” — apologies for the euphemism — are able to jump in at the very top of the technology curve represented in Martec’s Law, which gives them a strategic advantage.

Now, I’m way outside my field of expertise here, but to the degree that terrorist-type groups have little interest in building a stable, long-term organization — at least in the sense we’d think of for a business or government institution — they are relatively free to keep reinventing their tactics. They can restart at the top of that technology curve any time they choose.

That poses a very real danger. Instead of coordinating massive, multi-year “transformation” initiatives, they can transform and morph much more fluidly.

What’s our defense against such threats? Well, as demonstrated by the Portuguese navy, a good place to start is by understanding how those threats would materialize. Not as a one-time exercise, but as a continuous study in disruptive “start-up” (sorry, another euphemism) tactics.

This is red teaming to identify surprises before they surprise.

Hopefully, by understanding these tactics, national security forces can better apply their strengths of larger, more powerful resources to defend against them. Even if it’s not “efficient” — the ratio of defense resources to those of disruptive attackers may be imbalanced by multiple orders of magnitude — the goal is making it effective.

Bringing this back to the domain of marketing and business, what’s the takeaway?

In all humility, I’d agree with the commenter from the start of this post: it’s an affirmation that Martec’s Law is a real phenomenon. Everyone — everyone — is wrestling with the widening gap between technological change and organizational change. If you’re feeling the pressure of that chasm, you’re not alone.

And like the Portuguese navy, it’s probably wise to invest effort in understanding how potential competitors in your market would leverage cheap, new technology to disrupt your business.

It’s perhaps another, maybe even more realistic, justification for a “labs” unit. Not just to invent new products or go-to-market motions that you’ll fully take to fruition (the adoption rate of such projects at scale is relatively low). But at the very least to understand how competitors could disrupt you, so that you’re prepared to adaptively defend against them.