A few weeks ago, an internal memo from Google (or so it was claimed) was leaked that warned, “We have no moat.” Allegedly, it was written by an AI researcher at the company who was explaining how the real competitive threat to Google’s generative AI initiatives wasn’t OpenAI. It was open source communities.

If you want to understand the enormous power of ecosystems — and if you’re in martech, this may be the most important topic of your career — there’s a true masterclass in the subject playing out in front of us.

A super short summary of that memo: while Google and OpenAI were busy investing in their own massive but “closed” large language models (LLMs) with Bard and ChatGPT, a foundation model from Meta — LLaMA — was released/leaked as open source. Within a matter of weeks, hundreds of independent developers all around the world built upon that model in ways that rapidly approached the performance of Bard and ChatGPT, but at a fraction of the cost. They found ways to make the model smaller, run on laptops and even mobile phones, accelerate training and tuning, and more.

Meta’s LLaMA was taking off as a platform for ecosystem-led innovation.

“Plainly put, [the open source community is] lapping us,” the Google memo stated. “Things we consider ‘major open problems’ are solved and in people’s hands today. … While our models still hold a slight edge in terms of quality, the gap is closing astonishingly quickly. Open-source models are faster, more customizable, more private, and pound-for-pound more capable.”

Pause here for a moment.

Consider: a trillion-dollar company with many of the world’s most talented AI developers — this current wave of generative AI is based on their invention — and billions of dollars to spend can’t keep up with the speed of innovation of an uncoordinated mass of hobbyists, students, and tinkerers.

“The value of owning the ecosystem cannot be overstated,” the author concludes (emphasis theirs). “Google itself has successfully used this paradigm in its open source offerings, like Chrome and Android. By owning the platform where innovation happens, Google cements itself as a thought leader and direction-setter, earning the ability to shape the narrative on ideas that are larger than itself.”

Why ecosystems are often underestimated at first

What is the deadliest animal on earth?

Great White sharks? Bengal tigers? King cobras? Cocaine bears?

Nope. It’s mosquitos, which kill 725,000 people every year by spreading disease. Sharks, in comparison, kill about 10.

Now, don’t take that metaphor the wrong way. My point is that just as people underestimate mosquitos because of their individual size, large companies often underestimate the impact of many, individually small contributors in an ecosystem.

Large companies tend to view the world in terms of big chunks:

- Who are big competitors that threaten them?

- What are big M&A deals that can significantly expand their market?

- What are big products they can launch that will generate big revenue streams?

Hey, those are totally valid ways of thinking about their strategic landscape. When you’re big, only big things move the needle. But this focus on individually big things can cause them to overlook swarms of small things that can be very big in aggregate. They’re looking for Jaws in the water from a beach tower while unconsciously waving away the mosquitos circling right in front of their eyes.

They can think — as perhaps Google did with their initial approach to generative AI — that their size uniquely enables them to drive breakthrough innovation. But in truth, innovation often happens in a more evolutionary way, with hundreds or thousands of experiments and iterations that converge in a paradigm shift (as in the Thomas Kuhn definition of scientific revolution, not eye-rolling corporate-speak).

Small companies, entrepreneurs, and individuals are much better suited to embracing that frenzy of experimentation. They’re less constrained by existing products, revenue streams, org structures, budget committees, approval processes, executive politics, etc. Without that friction, they jump right to trying their ideas. And if one idea doesn’t work, they try another. And another. And another.

The magic here isn’t in any one person or team taking that experimental approach. It’s in a legion of them, all trying different ideas in parallel, cross-pollinating the winning concepts, building on them, competing with different variations. Most individual contributions to the field are small. But in aggregate they are a relentless force of nature.

It’s hard to replicate that dynamic of innovation inside a closed, large company.

There’s another aspect of size that escapes big companies and enables small ones, and that’s specialization. Big companies need big products that generate big revenue streams. This drives them to pursue broad horizontal offerings that serve wide audiences. That’s not a bad thing. But it filters out a vast range of more specialized opportunities that don’t meet the threshold of being an obvious $1 billion line of business in five years.

But for small companies, entrepreneurs, and individuals, those specialized opportunities are golden. They can build something that is the very best at what it does within a more focused domain. They can tailor it in ways that big-company, horizontal products can’t because they’re willing to ignore large swaths of the broader market in order to delight a smaller subset.

Ironically, some will grow to become $1 billion runaway successes by not requiring that as a pre-validated outcome at the start.

This is part of a broad cultural and market shift over the past three decades, what Seth Godin identified as “the end of normal” — the flattening of the bell curve distribution of consumer preferences — and the rise of tribes, catalyzed by the Internet. There are over 19,000 craft beers in the world. Over 5 million podcasts. 2.8 million subreddit communities. 5.9 million sellers on Etsy. A blog or newsletter for every subject imaginable (even one for strategic martech geekery).

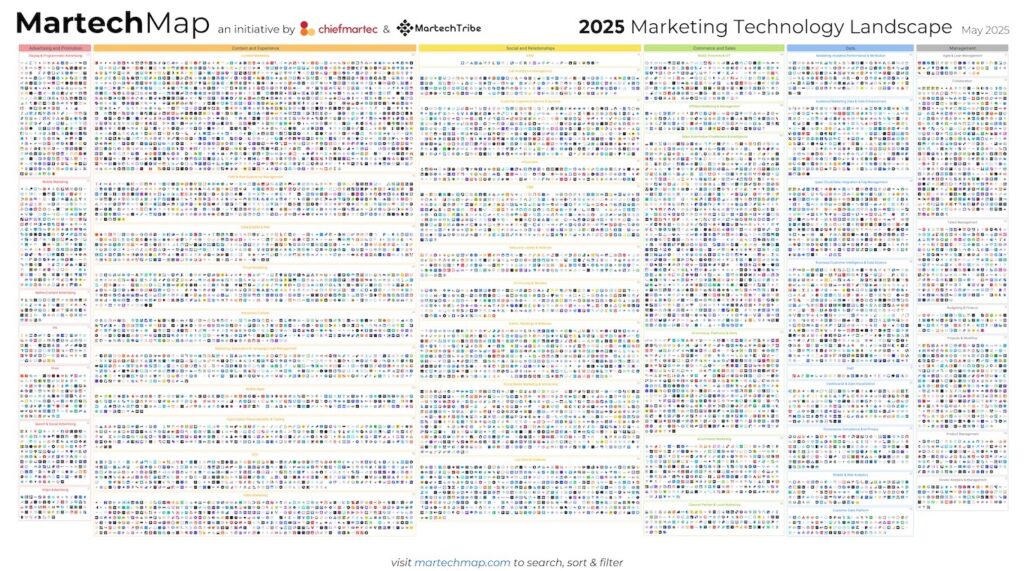

It shouldn’t be surprising that this same dynamic is happening in software. There are 1.6 million apps in the Apple App Store, 3.5 million in the Google Play Store. There’s 58,000 WordPress plugins. And, of course, 11,000+ martech products, which is just a fraction of the 100,000+ business software apps listed on G2.

The symbiosis of platforms and ecosystems

But here’s the catch. Nobody wants to deal with hundreds of fragmented, siloed products in their lives or their business. We want our choice of apps on our phone, but we want them to all work on our one phone. We’d never lug around a dozen different devices to use a dozen different mobile apps.

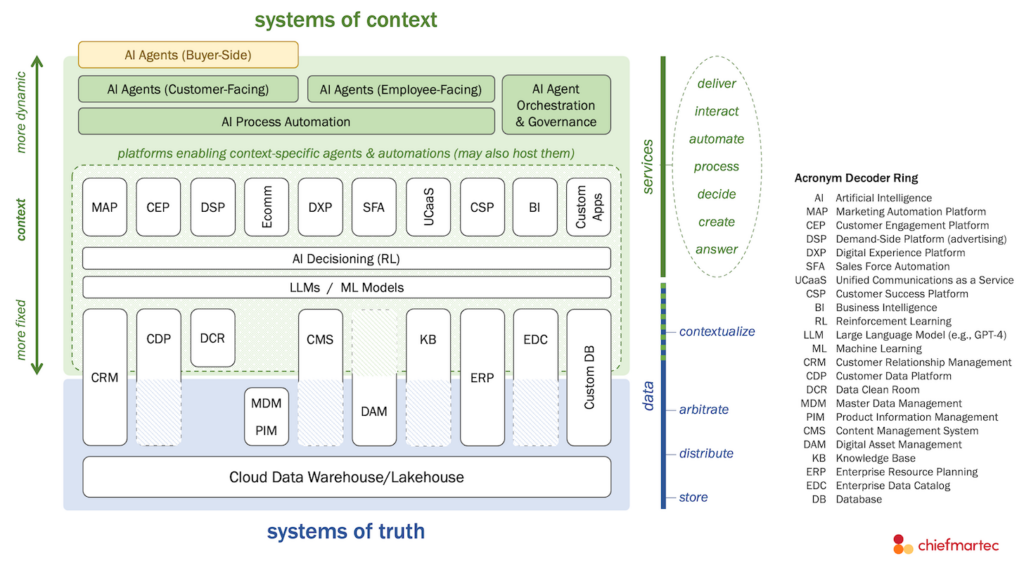

Platforms solve this problem by providing a common foundation upon which a set of apps interoperate. They serve as a coordinating device not only for shared technical standards but also for reach and reputation to a defined audience. They’re the center of gravity for a community of people who use that platform and its surrounding apps, which brings a ton of secondary benefits for all: best practices, career development, supporting services, talent networks, etc.

So what prevents a proliferation of platforms, pushing the problem down a level?

In general, software platforms need a large user base in order to persuade developers to invest in building to them. Development effort and go-to-market effort are zero-sum games: what you invest in one platform you aren’t investing in others.

Which companies tend to have large user bases? Large companies.

Do you see the beautiful symbiosis here?

It’s difficult for large companies to innovate through diversified experimentation themselves, and they can’t justify building products for niche markets. But they have a large user base at their core, for which they can serve as a coordinating force for other apps around them.

In contrast, thousands of small companies can innovate like the wind and address a long tail of specialized customer needs — but individually they don’t have the market power to serve as a coordinating force for all the other adjacent apps in their space.

It’s a match made in heaven. Potentially.

See, all those small companies, startups, and individual innovators have a ton of choices of existing and emerging platforms on which they can place their bets. A large user base on the platform is a major factor. But it’s not the only one. It matters what the platform enables them to build and how it supports their go-to-market. It matters if they trust the ecosystem to be a fair and level playing field, where they can win through their own merit. It matters the degree to which they feel appreciated and loved.

This rarely happens by accident, but by intentional choices of the platform company.

People tend to think that platform companies can act as “kingmakers,” able to pick winners within their ecosystem. (It’s tricky, and I generally don’t recommend it.) But in fact, it’s the participants in an ecosystem who are the real kingmakers. By voting with their development choices, they determine which platforms will thrive and which will wither.

I think that Google memo was right on the money.

Creating an ecosystem around your platform is both immensely valuable and incredibly hard to do. But the challenges that make it hard are the very reasons it can be a real moat. Once a company starts getting flywheel effects around its ecosystem — more developers create more value, which attracts more customers, which attracts more developers, and so on — it’s increasingly difficult for a competitor to usurp it.

In my opinion, generative AI will be all about the ecosystems.