At last count, there are over 11,000 products on the martech landscape. And while it’s been a tough couple of years for many SaaS companies, forcing industry consolidation through acquisitions or shutdowns, the number of new martech startups that keep entering the field remains remarkably robust.

Are these people nuts? Hold that thought. We’ll come back to it.

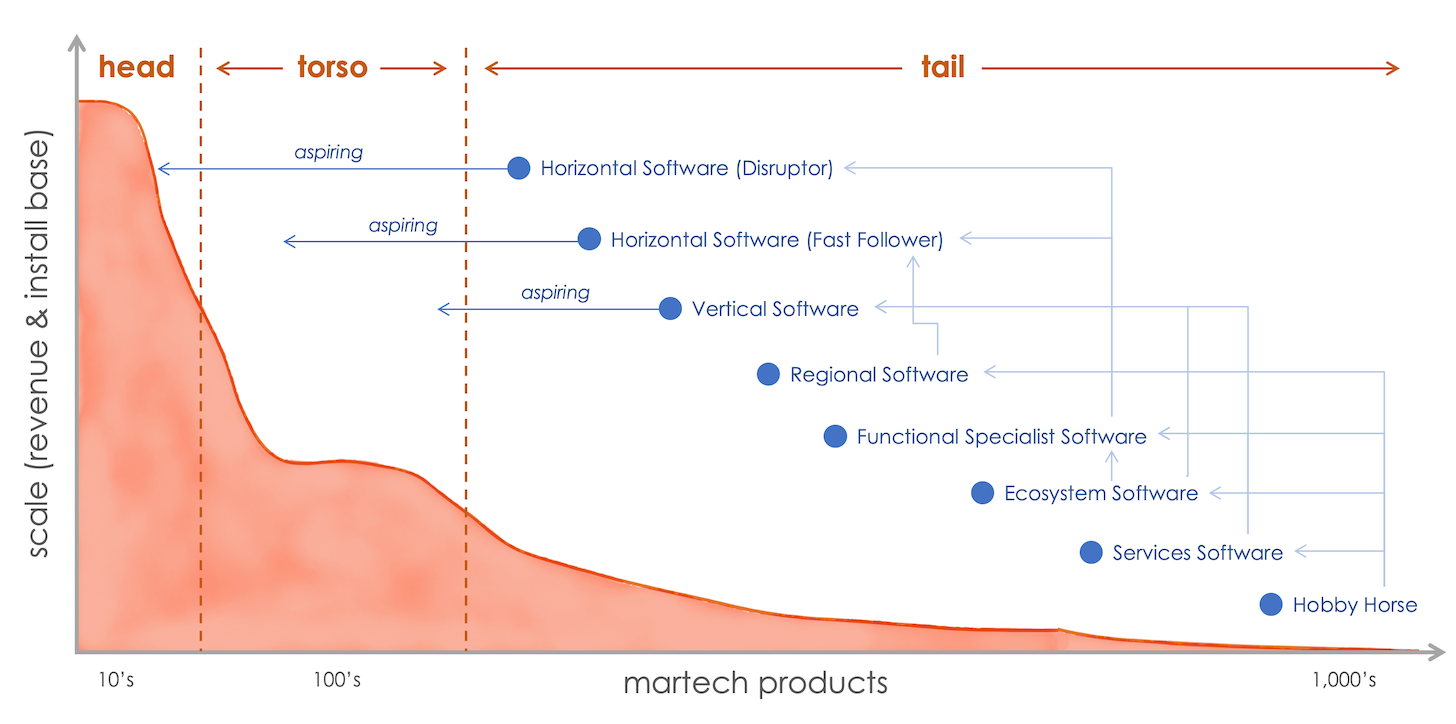

However, while the martech landscape is massive by the total count of companies on it, the scale of those companies varies dramatically. If we draw a graph of martech companies by their scale — measured by revenue and/or install base — it would be a quintessential “long tail” distribution, like the illustration above.

There are a small number of very large companies at the head of the tail, such as Adobe, HubSpot (disclosure: where I work), Oracle, and Salesforce. Think public companies with a market cap greater than $20 billion. Then there are a couple hundred category and vertical market leaders in the torso. When a company has crossed $200 million in annual revenue and is considered a top brand in their space, they’re in the torso.

And then there’s the long tail.

There are more than 10,000 “long tail” martech products in the market globally. Yet it’s probably the least understood segment of the landscape. It’s insanely noisy and risky, with relatively meager revenue per product on average. So why do people launch long tail martech ventures? Why do investors fund them? And why do marketers buy from them?

To answer that question, we need to recognize that the long tail of martech is not one homogenous sea of delusional dreamers. There are many different kinds of long tail martech products, with different aspirations and raisons d’etre. The impetus for their creation individually may be more rational than you might think looking at the market in aggregate.

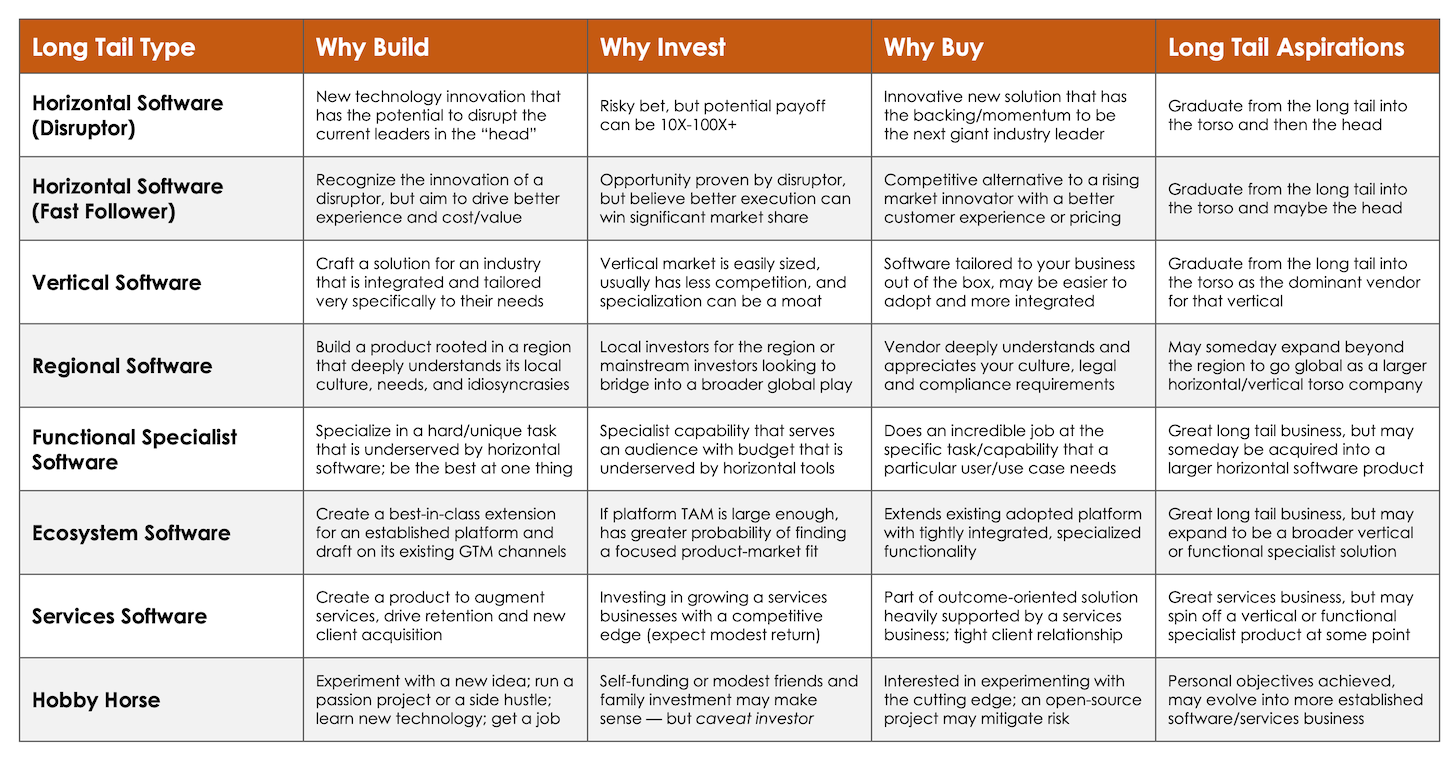

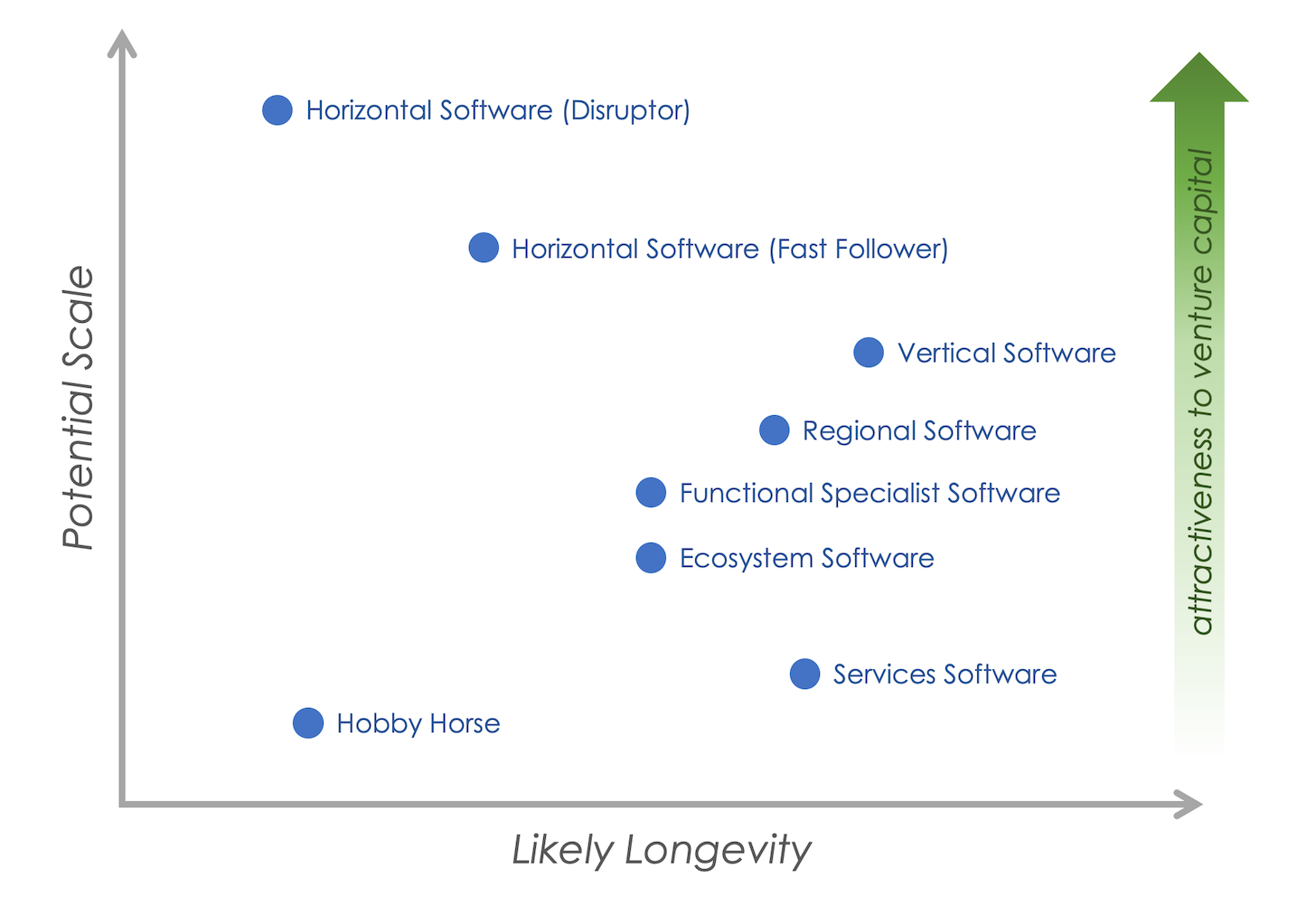

I’d categorize eight different kinds of martech companies in the long tail:

- Horizontal software (disruptor) startups — early stage, but big ambitions.

- Horizontal software (fast follower) startups — also early stage, chasing disruptors.

- Vertical software companies — specialize in a specific industry (small or large).

- Regional software — grow up embedded in a specific region and its culture.

- Functional specialist software — narrow focus, aim to do one thing really well.

- Ecosystem software — create a best-in-class extension around a larger platform.

- Services software — augment services offered for scale/efficiency/differentiation.

- Hobby horse — not (initially) intended as a scalable business.

Those first couple horizontal software ventures start out in the long tail. But their ambitions are to build large companies in the torso or the head. Unfortunately, this is hard to do. Most will not succeed at breaking out of the long tail and will either be acquired, go defunct, or limp along in a zombie state off into the sunset.

When people complain that “all these martech companies do the same thing”, horizontal software companies who fail to break out of the long tail are often the examples that come to mind.

But here’s the thing: some of these horizontal software ventures will become the break-out success stories in the head or torso. All of the leaders in the industry today started out that way. The big horizontal category winners emerge from the competitive jostling among many contending disruptors and fast-followers.

It’s a risky pursuit for those companies and their investors. But the potential reward can be commensurate with the risk — hence why these businesses attract a lot of venture capital.

But much of the rest of the martech long tail has a different dynamic. Vertical, regional, functional specialist, and ecosystem software products have less potential scale than horizontal ventures. But once they start to get traction, they tend to have a greater probability of success — albeit within a more limited total addressable market (TAM).

There are a lot more of these companies, but they each have their own “space.” You’re not typically going to evaluate them unless you’re in that particular vertical, region, functional specialization, or platform ecosystem. So they don’t add to choice overload as much as their sheer number would suggest.

Being in the long tail is not a bad thing for these companies or their customers. They may not be multi-billion dollar businesses, but they can be very profitable multi-million dollar businesses that are the best in their space and loved by their customers. And a few of them will evolve, typically by acquiring or being acquired, into larger head/torso businesses over time.

Software products offered by services companies also tend to be a bit different. They don’t necessarily have to be viable on their own. They’re often entangled with the services the firm offers. These products are sometimes used to acquire new clients as a (potentially loss leader) front-door. But they’re more often used to deliver differentiated or more efficient services — or to maintain a longer relationship with clients beyond more time-bounded projects.

Finally, there are the hobby horses.

This is my name for all the experiments, passion projects, side hustles that thousands of developers spin up every year. We’re seeing a ton of them around generative AI right now. Most are so small or so short-lived as to never even make it on to the martech landscape. But some do gain enough momentum to be visible. And the best of them may transition into “real” long tail businesses.

What’s unique about hobby horses is that they don’t need to become profitable businesses to be considered a success. The creators behind them can “win” by using these projects to learn new skills and technologies. They may build their personal brand. They may contribute to larger open-source movements in their space. Ultimately, it may help them get a great job and advance their careers. And in a very antifragile, evolutionary way, their micro-contributions help advance the industry.

These are the long, long, loooooong tail.

You probably won’t have to consider them in your selection set for evaluating serious new capabilities for your martech stack. But you might play with a couple of them in a purely experimental, low-stakes way to also learn and grow.

Martech’s long tail is challenging and complex. But it’s also beautiful in its own way too. So much raw innovation and invention. I hope by recognizing some of the differences between the types of participants in the long tail, you might see a bit of that beauty too.

By the way, these dynamics aren’t unique to martech. The same pattern appears in other SaaS categories too — engineering, finance, HR, IT, security, sales, etc. The software reviews site G2 recently published their Q4 2023 State of Software where they reported having ~125,000 B2B software products listed on their marketplace:

Almost all of these are long tail products too. Will this trend continue? Level out? Reverse itself? The morphing of software in the Age of AI has just begun, so it’s hard to predict. But I suspect we haven’t hit the ceiling yet.