The following is a guest post by Sergio Maldonado, founder and CEO of Sweetspot Intelligence.

Family storytelling die-hards may have heard of Bill Gordh, an award-winning, banjo-playing storyteller that has performed with the New York Philharmonic as well as at the White House Easter Egg Roll. He has also traveled extensively around the world.

I had the opportunity to attend one of Bill’s storytelling workshops a few weeks ago. Although he did not go into dissecting the specific tricks of his art, a few things called my attention:

- He turned a very basic script into an exciting adventure, peppering a rhythmic journey with various amusing stopovers that granted engagement. Then he rounded it up by making a dramatic scene out of a simple ending.

- He ensured consistency through repeated structural elements across his story’s timeline. This allowed children to easily follow and participate in a few guessing games.

- He added images to reinforce key episodes in his story.

When the workshop was over (and we proudly walked away with our own visual storyboard), I started thinking about all the misconceptions that now exist around storytelling in the marketing technology space.

Are we really using storytelling techniques in our regular exchange of data-driven insights? Can data visualization amount to storytelling, in itself? What are the missing pieces, if not?

Here’s a quick analysis of the very concept of storytelling as it applies to marketing and business in general, followed by a few thoughts on how to make the most of it in a data-rich environment.

Storytelling, deconstructed

Combining multiple alternative definitions into one, I would put this forward: Storytelling is the act of communicating ideas through the use of narrative elements with the purpose of educating, entertaining or influencing others.

A few key elements, therefore:

- Communicating: With the yet unanswered question as to whether human language has to be present at all, in oral or any other form. More on this in a few paragraphs.

- Ideas and purpose: These two come closely intertwined. Although a sequence of events may amount to a story, it is the underlying ideas that allow us to achieve our purpose in telling it.

- Narrative elements: Ideas alone are not stories. They must be tied to events or facts, which are put into narrative format to ensure emotional impact and future recollection.

An easy way to see these elements evolving and joining forces is to look back at the history of storytelling, as many of the ancient cultures we have come across left evidence of its usage as a means to transfer knowledge, explain the unknown or project authority.

The documentation of storytelling in our modern, business context can be traced back to Dale Carnegie’s theories on public speaking. Mr. Carnegie argued that stories are key to make ideas clear, interesting and persuasive. He also covered various techniques to succeed with real-life illustrations, including the focus on details and the use of words that allowed the audience to visualize “pictures” (such as proper nouns or figures, as opposed to abstract concepts).

This can easily be connected with the thoughts of Stanford University’s Jennifer Aaker in our current times: we extract meaning from the personal connection we make with stories, and this connection brings about an emotional side of decision-making that, we now know, precedes logic.

Storytelling techniques have abounded in multiple areas of business management. From David Ogilvy’s ads to Steve Jobs’ pitches, many well-known business leaders have successfully leveraged them. More traditional purposes have simply been replaced (disguised?) by our everyday business needs: selling, building strong teams, defining brands… or acting on data.

Together with these new purposes, the means by which storytelling can be delivered have also suffered their own evolution in the new, digital, context of business. It remains to be seen, however, whether we will eventually be able to find a clear break between form and function.

Form vs. function

Revisiting the first and last points in our definition of storytelling (communication, narrative): Is human language required? Is there storytelling beyond oral expression? Do podcasts and video qualify? Where do images, symbols and metrics fit?

Let’s try to answer these questions:

a) Narrative as a basic requirement of form

Narrative, as a representation of connected events, is perhaps the most crucial form factor in storytelling. Albeit it does not require words (think of a comic strip without dialogue), narrative does demand a sense of progress over time: events are placed along an imaginary timeline, even though flashbacks and parallel sequences may be at play.

Arguably, elements of consistency should also be present in narrative. These elements keep events tightly connected to each other regardless of the manner in which chronology is used. Though, of course, these elements are more tied to semantics than structure and, as a result, dependent on language, our next item.

b) Human language

One of the first books I happily bought in my early twenties was a bilingual (English-Spanish) copy of Anna Livia Plurabelle, the most widely discussed chapter in James Joyce’s last book, Finnegans Wake.

I was absolutely fascinated by the mere idea of the author making up his own language through conceptual shortcuts, and even borrowing terms from five or more languages as he saw fit to best express a given thought (which makes for a rather hopeless translation). I wondered:

Could human language become akin to “object-oriented” programming? Could we start adding levels of abstraction until the evolution of our species morphed our heads to look like those of the martians in our comic books?

Joyce’s original idea was simple, but extremely powerful: language determines the limits of our thoughts, and it is only through a richer representation of ideas/concepts that we can boost our own understanding of every experience.

Thousands of essays had been written before on the nature of language from multiple angles. While Kant considered it the ultimate representation of thought, Russeau called it an “instinctive expression of emotions”. In most recent times, Wittgenstein has defended the theory that language shapes our experience of the world. An approach that could be easily connected with Joyce’s: the limits of your language are the limits of your world.

Our very culture or experiences are reflected in the manner in which we employ or process words. While metrics and their various representations can be culture-neutral (and never entirely: take colors!), words are undeniably partial.

When we hear the word “subtle” we do not expect violent turns. When the word “problem” appears in a phrase, our brains prepare for impact. So even prior to dealing with elements of narrative, How then can the choice of words not prove essential to obtain a desired effect?

In other words (paradoxically enough), human language is not just form, but also function, when it comes to appealing to the emotions of others. Which in turn makes language itself unavoidable if storytelling is meant to have and emotional and memorable impact.

c) The language of images

If language is a combination of words and symbols (as these may simply represent such words or the letters they are made of), Where do images belong? Do they not share the same roots? After all, symbols, as a representation of reality were all we had before language even existed.

We could argue that many symbols would qualify as images as long as they remain “visual” representations of something (take hieroglyphs). But just as many symbols remain dissociated from real objects, images can easily fall short of becoming a symbol -e.g. by representing someone in merely descriptive terms.

As human beings, our ability to create images preceded written text by 32,000 years (records of the latter will “only” take us 8,000 years back), so it would make sense to accept that images played the role of written language while specific words were slowly being codified. Which in turn would separate our ability to understand the world around us from our capacity to asynchronously -not being present- communicate such understanding.

This denial of an “objective” understanding in the absence of words, coupled with a denial of images as a direct shortcut to the meaning of objects or scenes being represented is fully consistent with our everyday experiences. Suffice to quote digital analytics guru Avinash Kaushik in relation to using “stock photos” when presenting data insights: “Photos are very personal. We bring our biases, our life experience [… ]. You lose control of the story”.

But surely we cannot abandon our faith in images. After all, they are worth “a thousand words”, or so we often repeat without much questioning. Do we refer to its ability to communicate while being presented? Are we talking about our ability to remember instead? How about its potential to educate, entertain or drive action?

I was very happy to come across a study that finally dared to explore this assertion further. In Reduction and elimination of format effects on recall, Paul W. Foos and Paula Goolkasian focused solely on memory and concluded that an image was in fact worth 1.5 printed words (and little more than a single spoken word).

This is all very interesting, but we would still need to draw the line between images replacing “language” (photographs, conceptual or descriptive drawings) and images representing numbers. Do we process metrics (and their graphical representation) differently or do we transform them into words/language?

d) The language of numbers

“Number sense” is the term regularly used to describe the intuitive understanding of numbers by human beings. This entails our ability to count, but also any other animal’s ability to perceive changes in a number of things in a collection.

But back to our question: Do we process numbers independently from language?

Only to a very limited extent. As some studies show, it is through language that we are able to link up our small, exact number abilities (naturally being able to count up to three) with our large, approximate number abilities (naturally being able to understand that we have “many” things). In other words, mathematics requires abstraction, and abstraction is built on language and symbolic representation -a numeric system.

This is even supported by archeological evidence that language predates numeracy. Not to mention the many illustrations of language influencing mathematical ability.

So we must accept a close relationship between human language and mathematics, but, as discussed earlier, numbers and their symbols are actually language-neutral. And insofar as they allow us to build a substitution layer that is common to multiple languages, they provide a means of record and communication that is dissociated from human language… and the empathy that comes with it.

Jennifer Aaker’s thoughts come very handy once again. Speaking at the 2013 Future of Storytelling Summit, the social psychologist explained (and illustrated with data) that stories are memorable, impactful, and personal in a way that “statistics” are not.

e) Audio and video

Recent decades have taken recorded human language beyond text and images, to audio files and video recordings. Digitalization has made both of them widely available to anybody with as little as a mobile phone. Neither podcasts nor video files have not stopped growing in popularity in the business context.

On the basis of the previously mentioned Foos and Goolkasian study, a podcast would have a stronger impact than written text, if only in terms of our ability to remember the underlying message.

Video format can take this even further, allowing us to support such recorded speech with visual elements, while avoiding a lack of control in the manner in which message and visualization are processed together. In other words, video provides a synchronous illustration of recorded speech that becomes the closest thing to oral communication. As a disadvantage, however, all supporting elements of the story would have to be embedded within the video, conforming a self-contained piece instead of an effective complement to other environments where, for instance, data becomes the primary context.

Storytelling meets data

In summary, data visualizations cannot amount to storytelling. Void of language, they are unable to independently transmit ideas, clear purpose and emotional impact.

The very concept of “data storytelling” seems to me rather far-fetched as a result.

This said, as business management is increasingly more data-driven, metrics are indeed becoming a crucial part of any story. After all, data visualizations do provide excellent support when metrics are part of the story.

This said, as business management is increasingly more data-driven, metrics are indeed becoming a crucial part of any story. We could ask ourselves, however, on a case-by-case basis:

- Is the data shown at the heart of the ideas we aim to communicate?

- Is having an impact on the metrics being represented the purpose of the story?

Storytelling is often put at the service of entertainment or coverage of current events when none of these conditions (ideas and purpose, as per our prior definition) is met, with data playing the role of providing additional context or back-up information. Multiple examples of this can be found in the media. As such, supporting data visualizations will range from static point-in-time charts to open, reader-driven visual discovery widgets (providing a tool for the audience to retrieve valuable related information).

If only the first condition is met, storytelling will be at the service of information delivery (an equally legitimate scenario in data-driven management) or the exercise of influence, having an impact on other business metrics not directly related to those on display -e.g. higher-level objectives in the organization.

If, however, both conditions are met, storytelling will have been put at the service of data actionability. The impact of human language is in this case required to provoke a measurable reaction on the part of internal stakeholders in the face of a particular set of metrics. A combination of author-driven data visualizations, language and images will be at play in this case.

This (“action-driven storytelling”) could happen as a stand-alone effort or as part of predefined process. The first one can be as simple as an infographic (combining words, symbols, images and numbers in a logical arrangement that favors sequence). The second would be best understood in the context of Insight Management methodologies.

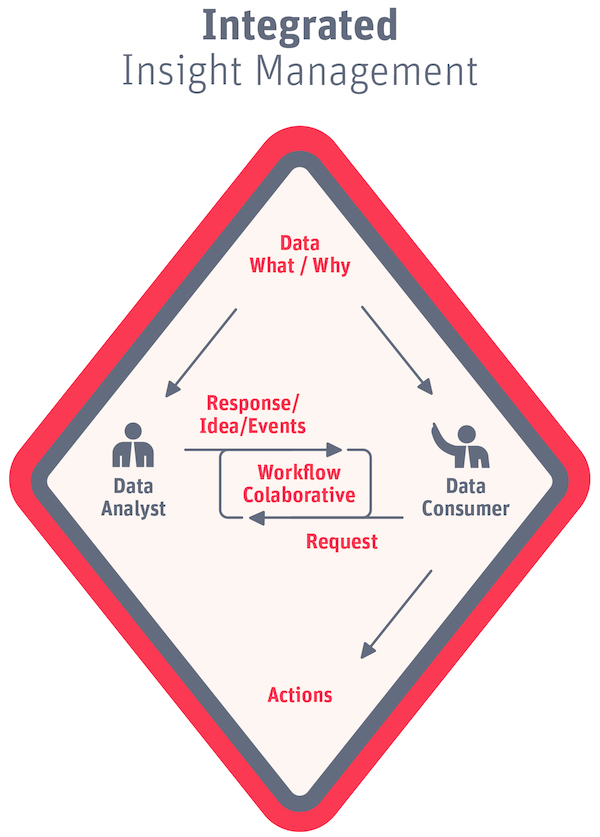

Under the original Digital Insight Management principles laid out by Eric T. Peterson in 2012 (in a paper sponsored by Sweetspot), digital analysts are provided with a means to accompany their insights with recommended actions (a “bottom-up insight delivery” process). Once acted upon (by decision-making data consumers), the impact of those actions is recorded along the timeline provided for each KPI.

This data-driven optimization workflow was soon followed by an alternative top-down approach to insight management (a “flagging” system), built on the premise that an effective distribution of metrics results in management being in the best possible position to dynamically define the priorities of the analyst’s job.

But there still was room for improvement. As businesses demand open, interoperable ecosystems, Insight Management had to become a natural part of existing enterprise collaborative and generic workflow environments. Furthermore, together with KPI updates, insights had to become ubiquitous, permeating other layers of internal communication or information delivery. And this had to happen in a way that supported author-driven narrative features.

This led to what we now call Integrated Insight Management, bringing about a new perspective of storytelling that is focused on performance, with words and narrative put at the service of data actionability.

Machine learning, automation and scalability

An elementary axiom supports all three insight management approaches (bottom-up, top-down, integrated): data analytics cannot happen without the intervention of data analysts or data scientists, no matter how sophisticated our tools or how clean our data.

Palantir’s Peter Thiel has supported this assertion better than anyone else in Zero to One (2014):

“We have let ourselves become enchanted by big data only because we exotize technology. We’re impressed with small feats accomplished by computers alone, but we ignore big achievements from complementarity because the human contribution makes them less uncanny.”

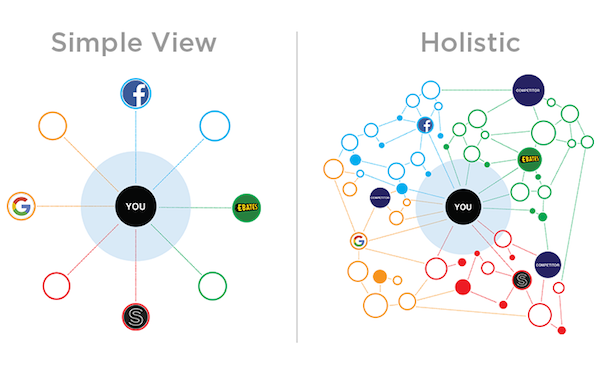

But we are never free of hype and fads (the new wave of storytelling has a lot to thank them for too), and so we are now faced with the collective illusion of “self-service business intelligence,” on the basis that data consumers — business stakeholders — can themselves be empowered with unlimited data exploration and forecasting capabilities across a myriad of structured, unstructured and semi-structured data sources, regardless of how incompatible or poor the various data models or data sets involved may be.

Besides a large amount of limitations (technical, performance-related and data governance-related), these attempts relegate storytelling and insight management to ad hoc reports and meetings aimed to obtain buy-in for a given action. In other words, they deprive organizations of the progress already made in connecting the dots between performance management, data governance and insight actionability.

But not all are bad news when it comes to automation and machine learning: a repeated “data»insight»action»measurement” process against a common set of metrics in a well-delimited business domain will result in a valuable repository of the best potential courses of action when faced with future challenges.

And there is much more within reach today:

- Automated generation of textual summaries of current performance against goals or past periods by combining the “what” that regular KPI updates embody with the “why” that their most closely associated dimensional breakdown represents.

- Text analytics to predict the potential impact of a given set of words.

- Automated reshuffle and update of pre-built infographic modules to shape stories that drive action.

It is certainly time to bring some of these together with our current storytelling and insight management capabilities.

Final thoughts

The division of roles in the marketing data space (analyst-data consumer-other stakeholders) is unstoppable, no matter how powerful our algorithms and grandiloquent our defense of “self-service BI”.

This plurality results in many data analysts and even more data consumers quickly becoming “data ambassadors” and “information delivery experts” in need of communication tools that ensure the impact of metrics (and their insights) on the broader organization, starting with the unmatched power of words.

Storytelling takes these words one step beyond, provoking emotional connections that drive action. I strongly believe that insight management methodologies provide the best possible grounds today for this powerful tool to thrive.

Data integration and analysis endeavors have already taken irrational amounts of budget and time for the little real impact they have had on the large organization. I believe it is time to put a fraction of such investments on the effective delivery of metrics and data insights. And I suspect this people-focused layer holds the answer to justifying every other prior effort.

Thank you, Sergio! For those of you who would like to read more about this topic, Sweetspot Intelligence offers a white paper that combines in-depth coverage of these and other points with case studies and product screenshots, available here: The Marketer’s Path to Data-driven Storytelling and Actionable Insights.

Much appreciated, Scott. And here’s the right link to that paper 🙂 http://www.sweetspotintelligence.com/en/ideas/knowledge/data-driven-storytelling-actionable-insights/

Thanks Sergio, I wondered where it went.

A terrific, thought provoking read that I have already shared as widely as my reach enables..

Much appreciated! Looking forward to taking the discussion further. Best

Good article Sergio, particularly your approach to insight management and how the analyst and consumer must behave collaboratively