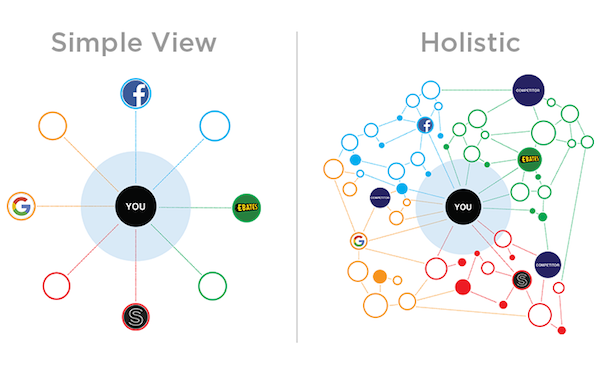

Let’s face it: we’re swimming in a sea of essentially infinite data at this point.

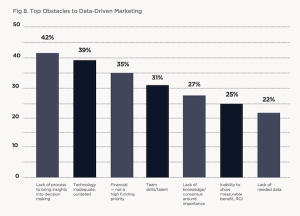

In a recent Teradata report, “lack of needed data” was cited as the least common obstacle to data driven-marketing. Only 22% of the marketers surveyed said that’s what held them back. The most common obstacle? “Lack of process to bring insights into decision-making.”

Data may be marketing’s most underutilized asset, but it’s hardly its most scarce.

Teradata honed in the on the process portion of that top obstacle, declaring that “process is the new black” in marketing. I agree, process is important. But let’s dig a little deeper into the decision-making part.

Decision-making is about making choices. And making choices is about strategy.

Strategy helps you make good choices

A.G. Lafley, the CEO of Procter & Gamble, made a simple but powerful statement in his book Playing to Win that really stuck with me. “Strategy is choice.” There are essentially infinite choices in business. Strategy gives us clear rules of thumb by which to make those choices.

A couple of years ago, strategy professor Richard Rumelt published the book Good Strategy, Bad Strategy. He eloquently rants that strategy is not a vision, it’s not fluffy words, and it’s not goal-setting. When those things masquerade as strategy — which they do with alarming frequency — he calls it bad strategy.

Good strategy, in contrast, has three key elements:

- A diagnosis (the why).

- A guiding policy (the what).

- A set of coherent actions to get started (the how).

In Rumelt’s own words: “In business, the challenge is usually dealing with change and competition. The first step toward effective strategy is diagnosing the specific structure of the challenge, rather than simply naming performance goals. The second step is choosing an overall guiding policy for dealing with the situation that builds on or creates some type of leverage or advantage. The third step is the design of a configuration of actions and resource allocations that implement the chosen guiding policy.”

That initial diagnosis is a choice: what’s the primary challenge that the business faces and why? Every business usually has a long list of challenges, each of which often has many competing explanations. A good diagnosis doesn’t spread itself across all of them. It pinpoints one or two that are the most important. It doesn’t shy away from the tough ones.

A guiding policy is also a choice: what advantage will we leverage to conquer the diagnosis?

And of course, the actions we take are all choices — hopefully made coherently under the umbrella of our guiding policy.

Strategic data helps you make good choices too

Data, data everywhere,

but what are we to think?

Back to our challenge of infinite data. Just as Rumelt distinguished between good strategy vs. bad strategy, I believe we can look at data in a similar way. Good data helps us make choices in the definition or execution of a strategy.

Bad data, on the other hand is merely data that we show off for its own sake. It presents a facade of being analytical. There are dashboards and visualizations, infographics and reports, and plenty of pretty PowerPoint slides. But it lacks purpose. It may tell us if we hit our goals or missed them. But it doesn’t help us achieve them any better than saying, “Try harder!”

Take KPIs for example. What does the phrase “key performance indicator” mean? We’re either performing or we’re not. Sure, that’s good to know — we especially want to be alerted when something that was humming along suddenly stops working. But KPIs don’t inherently tell us how to affect performance. The engine light in your car may motivate you to visit a mechanic, but it doesn’t help the mechanic actually fix your problem.

Maybe “bad data” isn’t the best phrase for this, because it isn’t a question of the data being accurate. It’s a question of the data being useful.

A better way of thinking about it may be strategic data vs. data theater. Through the lens of strategy-is-choice, strategic data helps us with our choices. Data theater, in contrast, doesn’t help us with choices — or doesn’t help us with choices that are coherent with our strategy. It may dazzle or disappoint us, but it doesn’t drive us.

What’s an example of strategic data? Data collected as part of a controlled experiment to test a hypothesis — if and only if the hypothesis is relevant to our strategy. The outcome of the test is intended to help us make a choice in pursuit of our strategy. This is why I believe that big testing is more important than big data — it helps us make choices.

Another good example of strategic data, a little more high-level and open-ended, is the data from Teradata’s survey of marketers and the obstacles they face in data-driven marketing. Based on that information — that marketers are most troubled by processes around data — Teradata can shape a guiding policy for marketing their solution to them. It helps them make a strategic choice.

Echoing Rumelt’s definition of strategy, strategic data helps us:

- Form or confirm a diagnosis (think of a diagnosis as a high-level hypothesis).

- Shape or enforce a guiding policy (an advantage is a high-level hypothesis too).

- Identify actionable hypotheses in pursuit of our guiding policy, plan concrete tests of those hypotheses, and measure the results — with the explicit purpose of affecting what we do next in pursuit of our strategy.

Strategic data has purpose.

Strategic data is not just useful to executives setting strategy at the top. It’s useful to those implementing strategy on the front-lines. That’s one of the greatest benefits the digital world has afforded us — front-line marketing efforts can easily engage in controlled experiments.

Note that the same data can be strategic or theatrical based on the presence — or absence — of such purpose. KPIs that are disassociated with choices are largely theatrical. KPIs that are being used to measure the outcome of an experiment in pursuit of your strategy are wonderfully strategic.

Forgive me for overemphasizing “in pursuit of your strategy.” But you can have forward-looking, predictive analytics that make recommendations for action — the fancy label for that is prescriptive analytics — but if those actions are disconnected from your strategy, it’s not strategic data. At best, it’s a distraction. At worst, it may interfere with or cancel out other strategic efforts.

Data-driven marketing has been held forth as a way to escape the inefficiency of “random acts of marketing.” But to be truly data-driven, we must also avoid “random acts of data” presented in colorful data theater.

Strategy is choice. And strategic data helps us make those choices.