Tech stacks are large. The empirical stack data we recently shared from Zylo, a leading SaaS management platform, showed that even after a year of belt-tightening, the average SMB (500 employees or less) still has 162 SaaS apps. Mid-market companies (500 to 2,500 employees) have 245. And large enterprises have 650.

This isn’t particularly surprising any more, is it?

Oh, and by the way, those numbers don’t include:

(1) Any custom apps the company has built, including with low-code or no-code platforms.

(2) Any apps that are personally used by employees without being expensed. Mobile apps are the most common examples here: social media, learning, personal productivity, creative tools, etc.

(3) Any apps that freelancers or hired services firms — agencies, consultancies, or other outsourced providers — are using. You can say that’s not part of your tech stack, but in a lot of cases, inputs and outputs flow between their stack and yours, even if it’s through manual processes.

(4) A tremendous number of free or freemium websites that employees use that nobody thinks of as “apps”, even though they’re delivering data or functionality that help run your business. Do you consider Google search an app? Probably not. But it’s one of the largerst and most sophisticated pieces of software on the planet, and no doubt your employees rely on it every day.

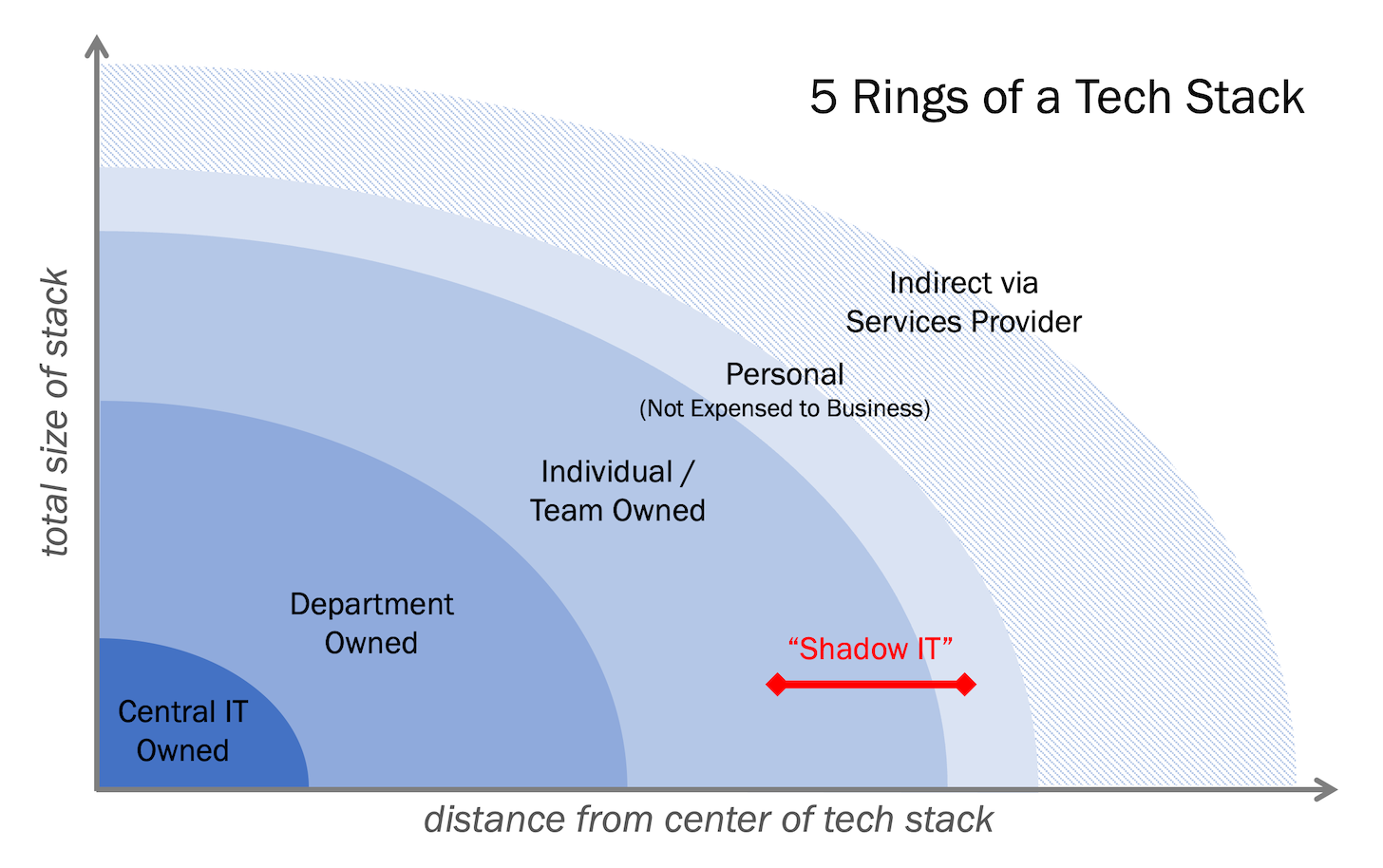

All this is to say: software permeates everything. It’s hard to get a true count of all the apps in play for a company, because the further away an app is from central IT’s “managed” part of the tech stack, the less visibility we have.

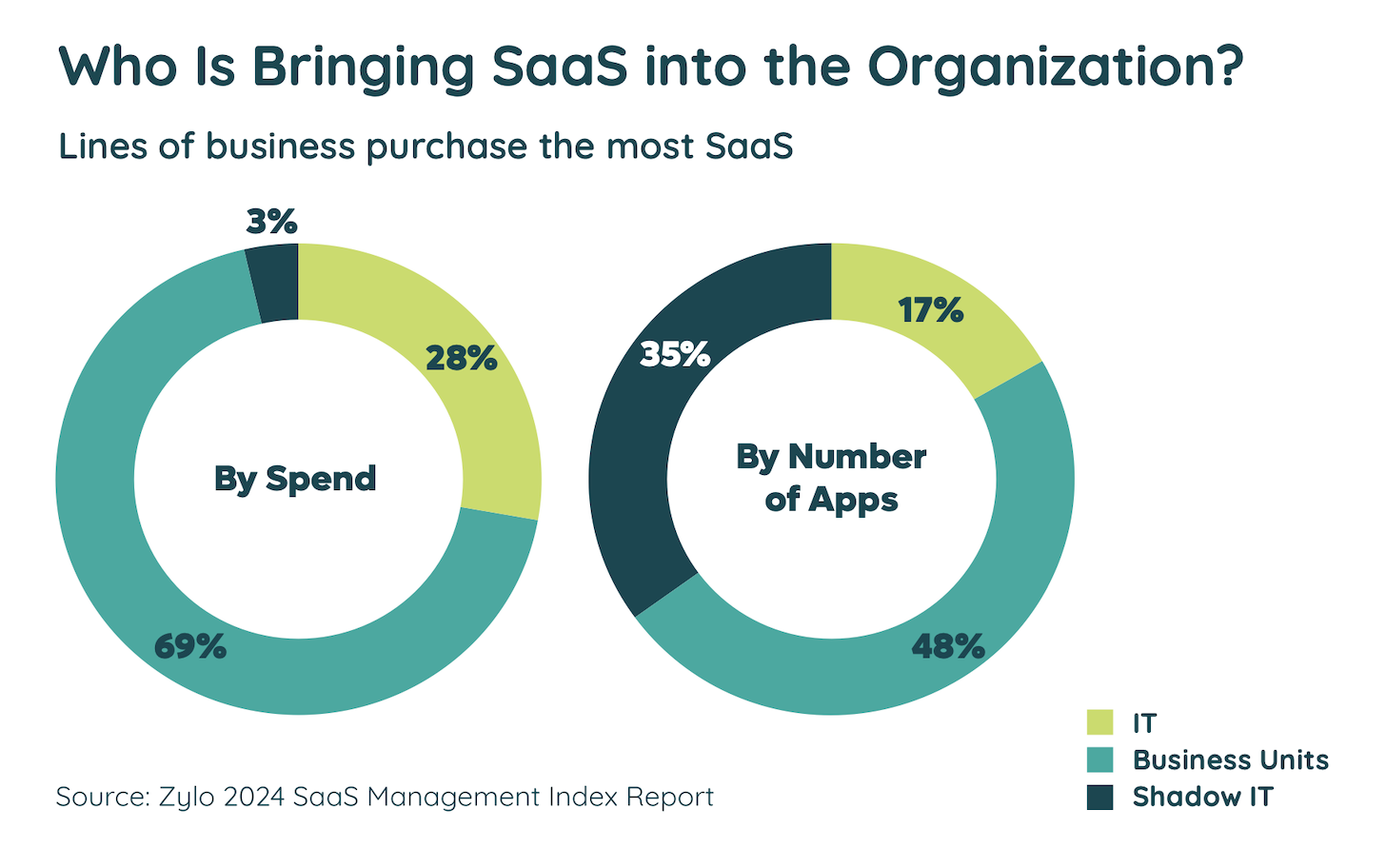

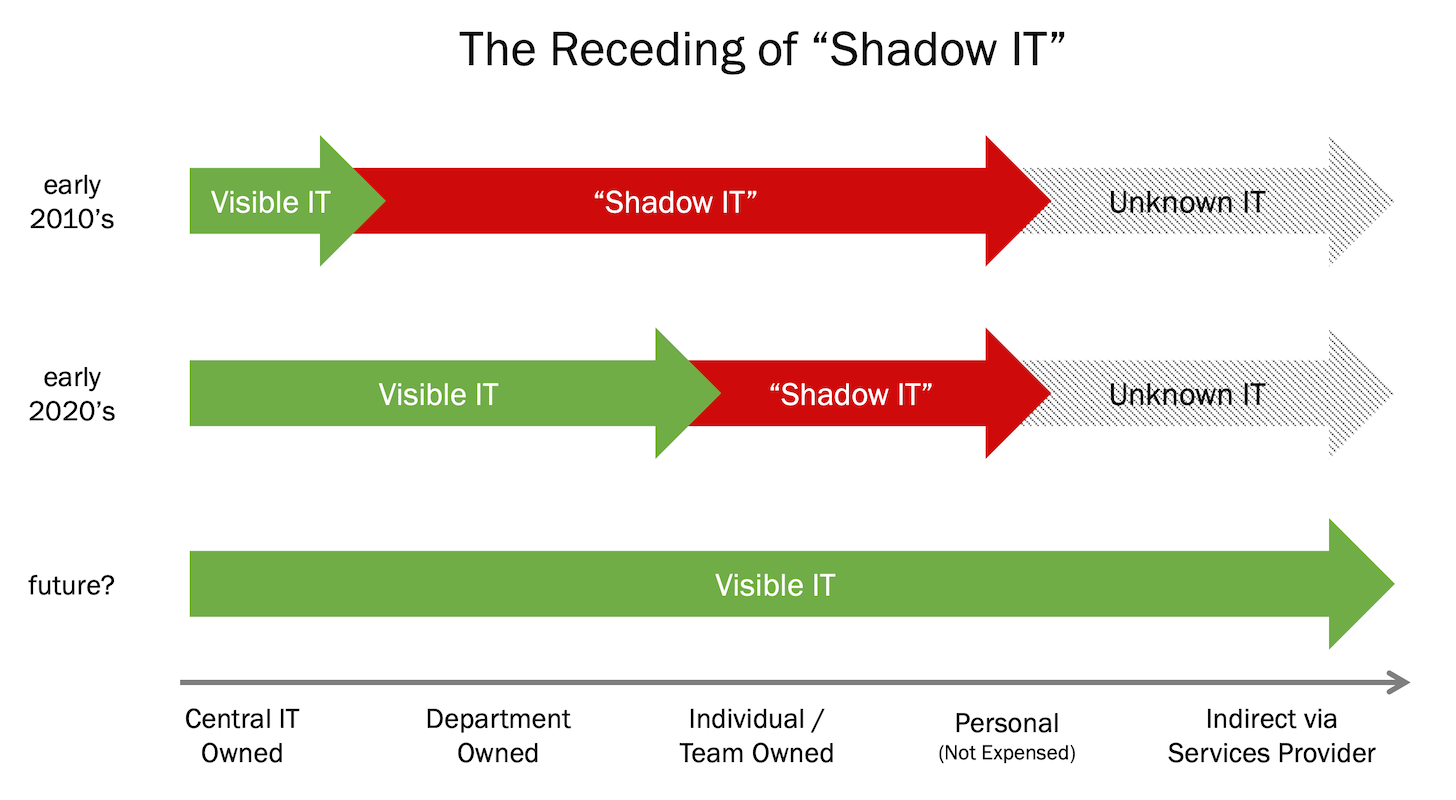

This foggy frontier is where shadow IT lives. But the border of visible IT has been steadily shifting outward. It used to be that any app not directly managed by IT was considered shadow IT. Now, department-owned apps have moved from the shadows into the daylight and make up the largest percentage (48%) of officially managed apps in tech stacks. And they’re the majority (69%) of the spend.

In contrast, IT-owned apps account for just 17% of apps in stacks and 28% of the spend.

Fascinating, isn’t it? Department-level apps — formerly known as shadow IT — have now overtaken IT in total count and spend. More than a decade ago, a pioneering analyst at Gartner named Laura McLellan predicted that CMOs would spend more than CIOs on technology. A lot of people thought that prediction was nuts. Not me. She and I wrote a joint article for Harvard Business Review in 2014 explaining the dynamics driving that shift. I think we can safely say her predictive insight has been thoroughly validated.

Who is… The Shadow?

So what is shadow IT today? Zylo, whose empirical stack data I’m citing here, defines it as apps that are expensed by individual employees — perhaps for themselves, perhaps for their teams — that fall outside the official procurement and governance process.

It’s super interesting that such (redefined) shadow IT accounts for 35% of the number of apps in tech stacks — yet only 3% of the spend. It’s a lot of small apps.

The assumption is that such shadow IT is bad, like trans fats. The three main reasons:

- It may be wasted spend, duplicative of existing IT-approved licenses.

- It may be ungoverned by IT, presenting security and compliance risks.

- It may be disconnected from the stack, creating data and process silos.

These are all legitimate concerns. However, the first one seems less egregious when we recognize that it’s only 3% of the spend. The second and third are harder to quantify, but that cuts both ways: the expected costs of those issues may be small or large, and may only be revealed over time or from a probabilistic “Black swan” event.

But we really should consider the other side of the equation too. Why do people buy such shadow IT? Is it just to rebel against the Empire? With a SaaS subscription? Not exactly the stuff of Jedi legend.

Weighing the upsides of Shadow IT

Individuals and teams adopt SaaS products outside of their company’s official tech stacks for one primary reason: to enable them to better perform in their job.

It may be that there isn’t an app in the official tech stack that does what they need it to do. Or perhaps there is, but the way that product works is undesirable on some dimension: it’s too hard to use, it doesn’t have the right features, the outputs it delivers are subpar, it takes too long, it costs too much, they haven’t been sufficiently trained or enabled, etc.

I don’t have quantitative data to prove it, but everything in my experience and everything I’ve ever heard from other people who go outside their official stack to use other apps is that the benefits in creativity, innovation, and productivity are meaningful to them. It helps them Get “Stuff” Done. It pushs the frontier of the firm’s processes and capabilities. It helps prevent stagnation in talent and technology.

Now, that doesn’t eliminate the downsides. But it does present a non-trivial trade-off. There’s reward as well as risk — for individuals, but also for the company, which is ultimately the sum of its individuals and teams and their impact — balancing on the Scales of Shadow.

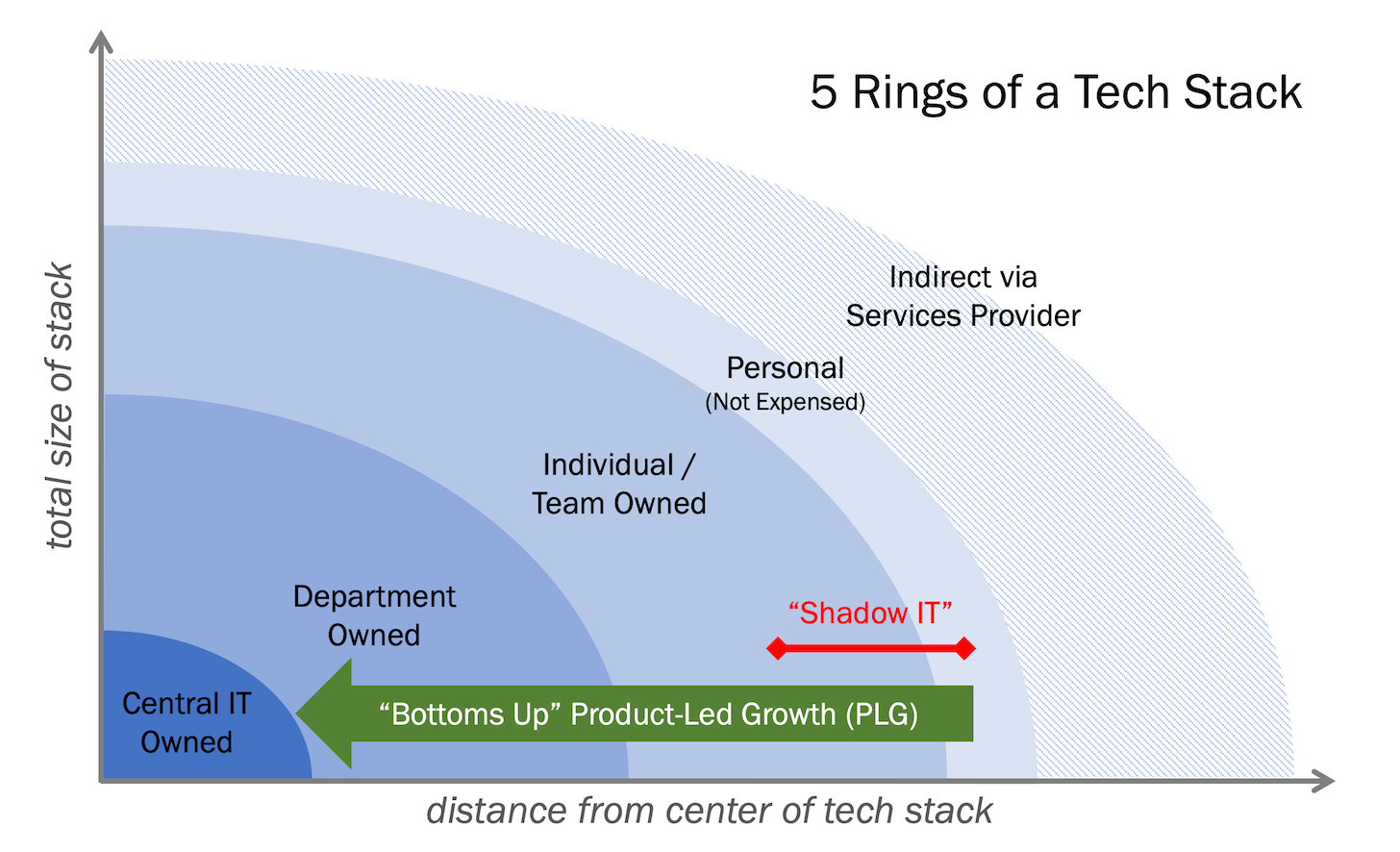

In fact, one of the reasons that such Shadow IT is so popular is because tons of SaaS companies have now built their products and go-to-market engines around the proposition of giving free, freemium, or low-cost/high-return value to individuals and teams. They prove their worth in the trenches, and then scale up to become officially adopted across the enterprise. Such “bottoms up” product-led growth (PLG) strategies have proven highly effective.

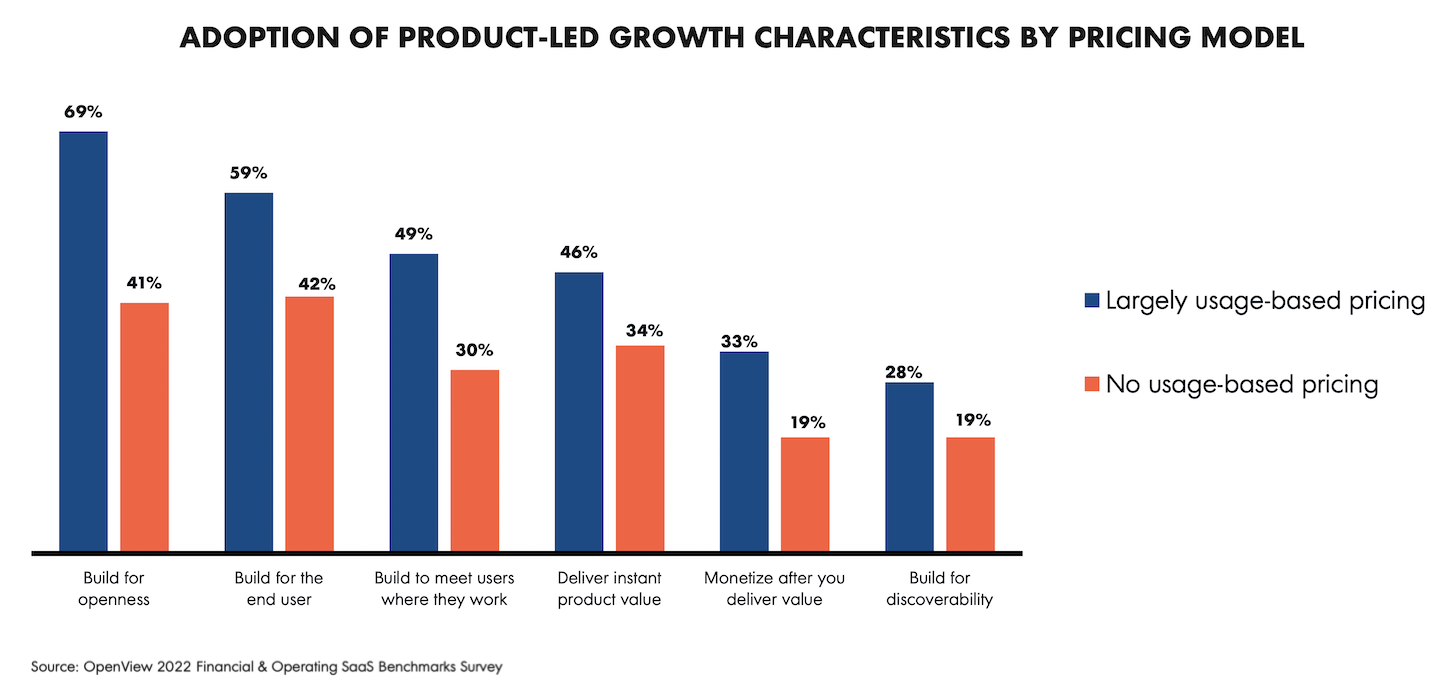

Yes, it’s a strategy that benefits those PLG apps. But they only achieve that benefit by delivering value. Consider the top factors that PLG companies focus on, for both classic seat-based licensing but also with usage-based pricing:

Build for openness and build to meet users where they work: they need to easily plug into existing ecosystems and workflows. Build for the end user: make users happy and successful. Deliver instant product value. Monetize after you deliver value.

You can see the appeal. Particularly because, in the eyes of many users, big legacy-ish enterprise-wide platforms haven’t expressed as much concern for their happiness and personal success. Now, that’s changing. But frankly, it’s changing because these PLG apps have created competitive pressure in the market, raising the bar for department-wide and enterprise-wide solutions.

One other major benefit that I believe comes from these bottoms-up PLG apps: better utilization. People use the apps they want to use. They resist using ones they don’t like. And the advantage of individual users and teams paying for their own licenses, inherently out of their own budgets, is that the buyers and the users are tightly coupled if not the exact same humans.

Those big, enterprise-wide deals for sweeping seat purchases? I suspect you’re far more likely to have unused seats lumped into that pile.

Taking this even further, PLG products that are leaning into usage-based pricing are driving the ultimate alignment between expense and utilization. You only pay for what you use, and you only use what gives you value.

Thank you, Chuck Norris Shadow IT apps, for pushing these usage-based models into the competitive dynamics of the market.

Eliminate Shadow IT by redefining it

Still, the downsides remain. And compliance, security, and siloization are heavy stones on the other side of the scales. But are there ways we can mitigate those downsides without losing the upsides?

I believe it’s possible.

One step is to de-couple technical approval and financial approval for apps used by individuals and teams. We’ve already done this at the departmental level. Marketing is responsible for covering the cost of the platforms they officially use, but those platforms increasingly go through an IT review for security and other compliance requirements.

Push that model further out to the edge of the org. Any app that an individual or team wants to use should undergo a security and compliance review. But the choice to pay for that app is up to the individual or team — and their ability to secure budget and justify its use. Don’t get me wrong, there should be pressure to justify the expense. But for small expenses, the pressure should be closer to individual and team, not in a distant department that likely has no direct stake in the use case.

But does that create more burden for reviewing a larger set of apps for security and compliance? Yes. But this doesn’t have to be one extreme or another. It can be a continuum, where there is a larger menu of apps that become approved. It’s not every app on the planet. But it’s not limited to just one in a category. And hey, maybe teams should “pay” to submit a new app to that review process.

I actually think this is a fantastic opportunity for SaaS management platforms, such as Zylo, to provide more vetting-as-a-service for popular apps. It could accelerate or optimize the review process for IT teams.

Other ideas might include a “sandbox” structure for new apps on the edge, that let users experiment with free or freemium apps in a limited fashion to determine if it’s even worth nominating them for review.

Users are experimenting with apps this way now. It’s just in the shadows because most companies haven’t created a good framework to let them do that experimentation in a way that’s visible to IT.

I’ll wrap this post up here, as a comprehensive write-up of all the possible ways to evolve the management of the apps-formerly-known-as-shadow-IT would like be a book. (Hmm.) But dismissing the upsides or ignoring the situation in the trenches is not, in my opinion, a sustainable strategy for companies competing in a rapidly evolving digital world.

We kill shadow IT for good by making all software visible.

And I didn’t even get to the invisible tech stack the lives beyond the boundaries of the firm, with all of one’s software-enabled services providers. A topic for another day.

Get chiefmartec in your inbox

Join 42,000+ marketers and martech professionals who get my latest insights and analysis.