If you’ve been at the intersection of business and technology for a while, you’re probably familiar with fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD).

I’m not talking about the natural stress, worry and concern that everyone feels in the course of their work. Instead, FUD is an intentional “tactic of rhetoric and fallacy” that has been used in sales and marketing, particularly in high-technology, to dissuade customers from considering a competitor’s products.

By many accounts FUD-as-strategy took hold with IBM in the 1970’s. Open source advocate Eric S. Raymond, author of The Cathedral and the Bazaar, sums it up like this:

The idea, of course, was to persuade buyers to go with safe IBM gear rather than with competitors’ equipment. The implicit coercion was traditionally accomplished by promising that Good Things would happen to people who stuck with IBM, but Dark Shadows loomed over the future of competitors’ equipment or software. After 1991 the term has become generalized to refer to any kind of disinformation used as a competitive weapon.

So the saying used to go, “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM equipment.”

By the 1990’s, however, Microsoft had become the primary FUD-slinger in the industry, ironically using FUD against IBM in the fight of Windows vs. OS2. (Yes, those who live by FUD, die by the FUD.)

Truth in Social Media?

It occurred to me that I haven’t encountered much FUD recently though — at least not in the computer hardware and software domain where it used to breed like rabbits. Granted, this is simply my own observation, not an exhaustive study. I’m sure there are cases out there. It just doesn’t seem as prevalent as it was 10 years ago.

Wondering about this, I have a few plausible explanations:

1. The Vanishing Sales Rep. FUD was always best distributed by salespeople — rarely did the attacking company want to take out a full page ad with a smear and risk backlash and litigation. Instead, it was sufficient for a “trusted” sales consultant to subtly spread bad memes. However, the sales dynamic in this industry has been changing. In Steven Woods’s book, Digital Body Language, he makes the case that:

The [online] sources of information available to buyers of complex products — that have traditionally required a consultative sales process — continue to grow in volume and quality. In the past decade, a buyer has achieved new capabilities to understand an industry’s trends, assemble a list of potential vendors, and analyze the best solution for their specific needs. The point to note: not one of these new sources has required the involvement of a sales professional.

So the original FUD distribution channel has been drying up. But wouldn’t it be just as easy — even easier? — to spread nasty rumors online?

2. The Democracy of Social Media. Sure, any vendor can post anything nasty they want about a competitor online, anonymously or otherwise. Joe at Company A, using the pseudonym Jane, can post in a forum a rumor that competitive Company B is losing its funding and all their customers are going to be screwed. But getting that rumor to take hold is another matter entirely. There are three problems with such slander.

First, the rumor becomes visible, indexed by Google, which gives the company that was attacked a chance to address it immediately. In the old world, malignant whispers were much less tangible and harder to counter in context.

Second, err, most anonymous postings aren’t that anonymous (we’ll save the privacy debate for another day). So the person posting the dirt (and the company he or she works for) runs a risk of being exposed, which can have serious legal and reputational consequences.

And third, anyone can post anything. Not just vendors, but customers. Since customers and other industry watchers far outnumber the vendors in most arenas, the dialogue around any given company is much more democratized than ever before. There are a lot more forum messages, blog posts, and Twitter remarks from non-vendors, people who don’t have a FUD agenda. These (relatively) independent voices often end up dominating the conversation. And woe be to the unscrupulous vendor that stirs up a competitor’s customers. There is something to be said for the wisdom of crowds.

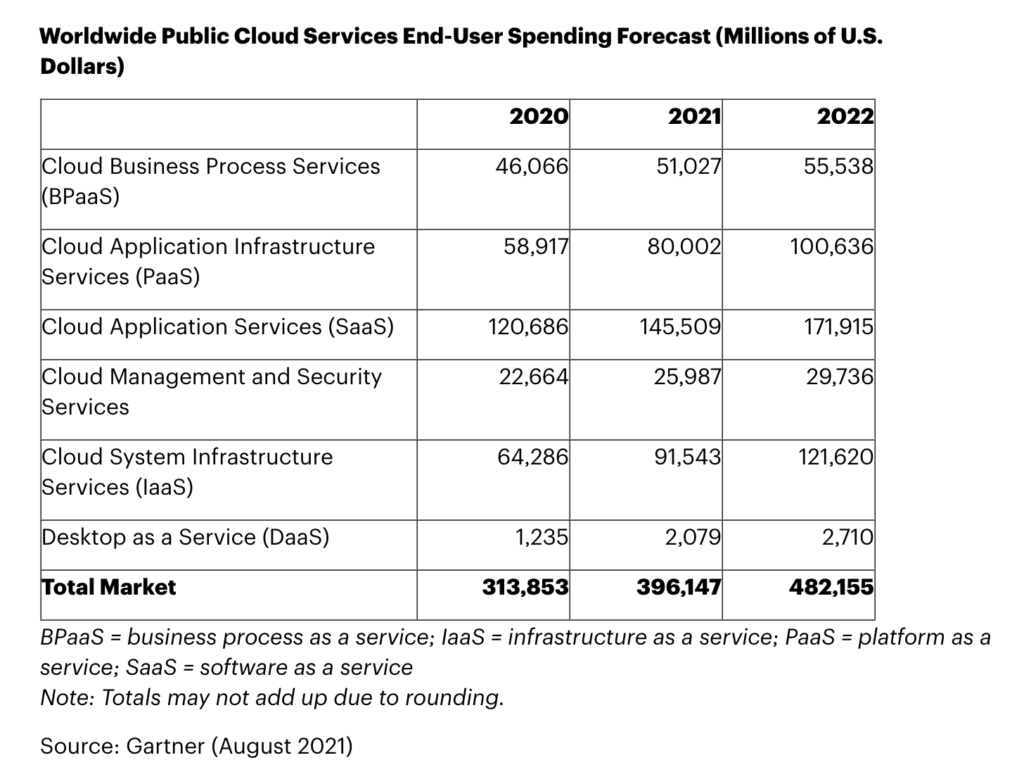

3. The Dynamics of Cloud Computing. Buying enterprise software and hardware used to be a major capital investment — you got one shot to get it right, and then you were stuck with your choice for years into the future. But with the new era of software-as-a-service (SaaS) and cloud computing, you have an entirely different set of dynamics:

- you can try before you buy (or at least do a small trial);

- you rent the software on subscription, less upfront investment;

- hardware purchase decisions are encapsulated out of view;

- you have performance-based service level agreements (SLAs);

- you can cancel your subscription at virtually any time;

- standardized data formats are more interchangeable;

It’s just a lot easier to try new solutions to see what they’re really like, and if you need to, it’s easier to switch. (Maybe still not yet easy to switch, but way easier than before.) Increasingly, companies aren’t just buying one mega software solution, but are weaving together a tapestry of many smaller and more specialized products — creating a “portfolio effect” that also mitigates overall risk.

It’s an environment where FUD rumors for any one vendor are inherently less effective.

To be sure, cloud computing — trusting your data and your business operations to servers outside of your control — has its own legitimate causes for concern. But as the reliability and uptime of web-based services continues to increase, in most cases demonstrating far more robustness than most internally-managed systems, this Dark Ages fear is being extinguished by the light of the Cloud Renaissance. Besides, many cloud-based software providers all use the same handful of infrastructure providers, such as Amazon and Rackspace. Nicholas Carr’s excellent book, The Big Switch, is a great read on this subject, comparing the rise of Internet-based computing with the rise of electric utilities in the early 20th century.

4. Google Does No Evil. It’s usually the biggest player in an industry that has the most to gain from FUD, as a way to stifle disruptive innovation from upstart competitors. In their time, both IBM and Microsoft each set the tone for FUD as an acceptable practice, and many followed their lead.

These days, Google is pretty much king of the hill, and to date, they haven’t yet engaged in FUD. One reason could be that their motto, “do no evil”, would be hard to reconcile with such Machiavellian dirty pool. Aside from PR image issues, it’s arguably not in their corporate culture. Of course, one could also say that they haven’t yet had a serious competitive threat to their dominance, and it won’t be until that happens that a real incentive for FUD-making will kick in.

But I think there’s yet another driver behind diminishing FUD…

Hope, Help, and Inspiration (HHI)

Call me a starry-eyed optimist, but I think we’re entering a post-FUD era because a new marketing mantra is thriving in its place: hope, help, and inspiration (HHI).

I think we owe this new mantra in large part to Google. Why? Search engine optimization (SEO). In online marketing today, everyone craves high organic rankings on as many terms as possible that their products and services might be associated with. Ideally, they want to be in the first few slots of the very first page of search results, so when someone does a query for, say, “CRM best practices”, they’re right near the top.

How does one obtain these top rankings? By publishing great web content on that topic that lots and lots of other people like and link to in their blogs, bookmarks, and social networks. Unlike celebrity gossip, this great content is rarely negative rumors about competitors, but instead a company’s own contribution to the community dialogue of “how to be successful with X”. It’s a huge kind of self-help market for business best practices.

So companies publish white papers, research reports, tutorial webinars, case studies, and reams of thought leadership blog posts and articles. Very often, these aren’t shallow propaganda pieces — which don’t generate much link love — but rather genuine and useful content, in many cases contributed by team members outside of sales and marketing with particular domain expertise. And when one of these contributions is recognized as being particularly valuable, other bloggers and social media magnets take it and expand upon it.

How do you compete with someone? You publish more and better content! It’s a virtuous cycle. Ultimately, the winners are the customers themselves, who end up with a plethora of excellent material to learn about what is possible. It’s a grassroots meritocracy that revolves around three variations:

- Hope — you’re not alone, and others have solved this;

- Help — specific answers to questions you’re struggling with;

- Inspiration — here are ideas of what is possible for you;

It may not be a FUD-free world yet, but taking the HHI road is arguably the best strategy in the new world of search and social media marketing. And isn’t it more rewarding for everyone?

beyond fear.there is sunrise,beyond fear there is life