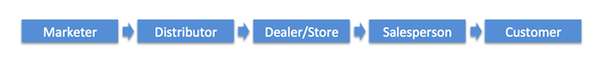

The Internet was supposed to be The Great Disintermediation Machine, collapsing the relationship between marketers and customers from this:

To this:

And indeed, that disintermediation has happened in many businesses. E-commerce is now over a trillion dollars a year. While some of that goes through Internet retailers like Amazon, much of it is direct with brands themselves. For pure digital businesses, such as software-as-a-service (SaaS) subscriptions — where the marketer and the customer are separated by only a credit card field on a web page — it’s about as direct as you can get.

For many, that’s a welcome relief. Channel management was immensely challenging, with “vertical competition” between the different parties up and down the chain. They jostled for revenue, rights, responsibilities, and information — with mixed incentives to cooperate for mutual benefit, while competing for their individual interests. Competitors could interfere at any of those junctions. These were complex, multi-stage market dynamics.

So thank goodness for disintermediation, right? Marketers can now interact directly with their customers, free from the concerns of interventions by intermediaries.

Well, not so fast.

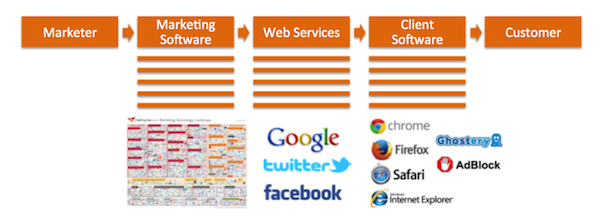

There is a new channel of intermediaries between the marketer and the customer, and it looks like this:

Think about it. In digital marketing, we don’t directly interact with the customer in the way we would if we were shaking their hand at a cocktail party. Software mediates all our interactions in the digital domain. Yes, that’s the same mediate from disinter-mediate. We have traded old intermediaries for new ones.

Everything in digital marketing is piped through this new “software channel,” and every code-powered piece along that path has the ability to affect both customer experiences and marketer perceptions:

- Marketing Software — all the marketing technology products that we use to build and deliver digital experiences to customers and to measure and analyze how those experiences work.

- Web Services — the Internet sites that connect us with our prospects and customers, such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, and a wide mix of other content, advertising, and social media hubs.

- Client Software — the software that our audience runs on their computers and mobile devices, including web browsers, browser plugins, and device-native “apps.”

There are a lot of “virtual hands” that touch what we’re sending downstream and what gets echoed back up. Indeed, at each stage along this chain of digital intermediation there may be multiple layers of software interacting together:

Each of these digital junctions along the way — through which our marketing intentions are transmitted and customer behaviors are received — acts as a lens that may alter, filter, warp, limit, color, block, enhance, magnify, or refract what is intended and perceived.

What we expect a customer is experiencing on the other end of this sequence, may not be what is actually happening from their perspective. What we observe from our dashboards and reports, having been filtered back up through so many software layers, may not accurately reflect the ground truth.

With this channel metaphor, there are five important points to note carefully:

1. Technology management is the new channel management. Just as traditional channel management was a big deal with physical world intermediaries, we should have a similar respect for the importance and complexity of digital intermediaries. Just as we had channel marketers, we need marketing technologists. Just as we had channel marketing strategy, we need marketing technology strategy.

2. There is vertical competition in these software channels too. All these different digital intermediaries want a piece of the pie, whether it’s software license revenue, advertising revenue, data collection revenue, etc. After all, each of them is owned by a company seeking to make a profit and grow its power in the world. They compete with each other, but they also compete with you — for time, money, and audience influence. You should understand the actors in this pipeline, in order to manage your relationship with them effectively.

3. This is why a large marketing technology landscape can benefit marketers. When you’re subject to vertical competition — i.e., leverage that other players along your channel have over you — you want as much horizontal competition among the firms at each of those subsequent stages as possible. You want them competing with each other, which gives you more leverage.

Of course, there are other factors to consider, such as ease of integration and sustainability. But as one marketer commented, “I don’t want consolidation. I want interoperability. I want choice.” To get a sense of what happens when too much power is consolidated in one stage of the channel, consider Google. They essentially control search marketing — any marketer who wants to be in search has no choice but to play by their rules.

4. Don’t underestimate client software as a powerful stage in the channel. Web browsers have largely competed as commodities, so this hasn’t been a factor for most marketers to consider — other than headaches with browser compatibility. But when browsers decide to unilaterally block third-party cookies, suddenly marketers realize just how much power is concentrated there. Browser plug-ins such as Ghostery and Adblock can have a big impact on marketing too. Apple’s iron-grip over its App Store — deciding who gets to distribute a client app or not — is another example of the strength of this last mile of the channel.

As more new devices enter our lives, there will be more client software — and the potential for the firms that own that software to wield tremendous power over marketing. Keep an eye on this.

5. Transparency into this channel is extremely valuable. The more you can know what is actually happening up and down the digital channel — even if you can’t fully control it — the better. I expect we’ll see more solutions designed to give marketers greater visibility, such as from marketing middleware (tag management vendors are a good example of this), service monitoring (e.g., search and social media monitoring), and client-side insights from panel-based audience measurement firms and technology companies such as Evidon.

As a related point, note that the more automation you build into your marketing, the more intermediation you’re creating. Not that you shouldn’t automate — just be aware of the trade-offs you’re making. I’d also be wary of black boxes in your marketing technology stack that don’t let you peek under the covers to at least audit what they’re doing, if not why.

Does this metaphor make sense to you? What characteristics about this new channel do you find most interesting?

And— in advertising —the old channel, Advertiser-media agency-publisher/network-measurer (i.e. Nielsen) cost 7.5% and was transparent. In the LumaLand of on-line, there might be 20+ nodes in the channel and cost up to 45%!

Great point, Linda!

I guess the only redeeming part of this new channel is that, outside of advertising, the media is asymptotically close to “free.” So there are definitely many more outstretched hands along this channel, the overall economics should still favor marketers. But since every percentage point counts to the bottom line, it’s certainly something to pay close attention to.

Scott

Strong points indeed. This is why we believe the horizontal middleware and infrastructure is so critical. If marketing isn’t capturing all the data from all the point solutions all the time, its nearly impossible to understand the true buyers journey. Black Ink ROI uses master data management to capture, hygiene, parse and map all the data across an entire enterprise (CRM, ERP, EMM). Otherwise how is a CFO and CMO able to provide business level reporting on Enterprise Marketing ROI?

Thanks, Jeff. I agree that the visibility that solutions like Black Ink can provide — checks and balances on the data moving through a company’s marketing technology stack — has the potential to be enormously valuable.

This model also explains why Google, Facebook and Amazon have a lot of potential become even stronger intermediaries then they are already. By controlling not only the distribution network (Google, Facebook), but also the consumption device (Chrome, Kindle) they can grab an disproportionate share of the value. If Facebook manages to solve its consumption device problem (partner with Mozilla or Microsoft or Samsung) and Amazon continues to build up Amazon.com as a platform that is not just distributing physical goods, but also digital media, they will have the chance to join Google’s dominating position

Really good examples, Lars.

Thanks in particular for pointing out Amazon! I have to admit, I keep suffering from a blind spot recognizing just how much market power they have — and how much more they’re in a position to acquire in the years ahead.

Thanks for the insightful article (as always), Scott!

@Lars: I agree with your observation. Just for learning purposes, it’s interesting to see how this works in the Chinese internet market (which is bigger than the US market) where some large players have not only monopolized the search market (like Google) and the advertisement market (like Google), but indeed also market access (like Amazon) and device access (like Amazon, Apple & Google). The concentration of course is government sponsored (or at least tolerated) in China, but I’m pretty sure it would work out the same way if it wouldn’t have been, because it’s pretty much the same structure.

If I combine this insight about both markets with Scott’s other recent article on marketing technology (1000 vendors) and use his arguments why a consolidation might not happen, then we see something interesting: a high, continuously growing diversity in the marketing software market, while other parts of the chain are going exactly the opposite direction.

Would the players from either one segment go into the other one and influence it? So, would marketing software makers be able to bypass the web services, or would those dominant players be able to buy sufficient (or the right) marketing software vendors to neutralize that threat?

I have some ideas about that. More people?

Thank you, Jeroen. Really interesting idea. Your observation of these dynamics in the Chinese market are fascinating.

To some degree, I think Google is the most integrated across these stages of the channel: Google Analytics as marketing software, Google.com and Google+ as web services, and Chrome and Android as client software.

If Microsoft could ever figure out what it wants to be in the 21st century, I’ve always thought that they might have a shot at participating across these different stages too.

Yup, let’s keep an eye on those two.

Microsoft is working quite hard on positioning and extending Dynamics: I meet them more in client pitches than I did before here in Europe. I’m excited to see where that’ll go in 1-2 years from now.

As for Google: wait until they open the connection between the Google-auth and Google Analytics and they make that connection actionable for their clients, for free….that’ll wipe half the vendors in the market away in just a few months. Maybe I shouldn’t tell them this….

I think for most marketing software vendors, to avoid fighting an unfair battle in a Google/Microsoft/Amazon-dominated world, the route is to bypass the webservices part of the chain and bring sufficient added value in connecting other types of services, for example offline customer experiences, or in connecting deeper into the eco-systems of their clients than those giants will ever do.

And now I guess I also told them our strategy…

Great post.

Having just done a pilot channel dis-intermediation exercise in the produce industry, to find it crashed and burnt, the realisation that established behavior is always more hard wired than we give credit for. Applying logic to behaviour change is a dangerous game.

Guess that is why banner ads are still hauling in big bucks , when we all know, 1. They do not work, and 2. half of what we pay is going to scammers anyway.

Allen

Agreed. Actual behavior complicates the best of pure logic. I’ve heard it said by many people that the real mission of marketing technology management is actually “change management.” I believe that’s true.

Scott, it is not as simple as you imply. We are discussion The Age Of The Self-Transacting Customer” with our tech industry clients and what this means is that, even if the customer orders or buys technology direct online, they are still influenced, advised, consulted referred and helped in various by channel partners. We then help both vendor and channel partners adjust to this way of working together (eg. incentives, enablement).

Peter — I admit, this article is highly oversimplified. And indeed, many companies still have traditional channels as an integral part of their business. The main point I was trying to make is that even the “direct” digital channel is subject to powerful dynamics of all the software components along that path.

The combination of both physical and digital channels is extremely fascinating — and even more complex. But as you point out, it’s the reality for many businesses today.

Scott, great piece of work and food for thoughts. I particularly like the “technology management is the new channel management”. Definitely experiencing it in my day-to-day role.

Thanks, Adriano — really glad to hear this resonates with your experience!

And to add to Peter O’Neill, many businesses want simple, even single sourcing for their purchases from one (or two) vendors – that is part of why the channel model will stay strong. Along with the channel as trusted advisors. Unless of course a business is willing to hire more people to research, order, pay-for multiple technologies from multiple vendors. A lot of business do not have dedicated internal IT or tech experts.