Two trends, each racing forward, that have the potential for disastrous collisions:

- The need for truly customer-centric organizations in a fully connected world.

- The use of algorithms, predictive analytics, and big data to optimize everything.

In many cases, these can be synergistic. But some are train wrecks.

I experienced just how badly those two things can clash first-hand this week, when the Westin Cleveland Downtown reneged on my supposedly prepaid reservation at Content Marketing World. I won’t rehash that here, but I do want to step back and evaluate the role technology appeared to play in this.

According to what I was told at the Westin, the hotel overbooked to the point where about 30 customers were denied their reserved rooms. One of the managers pulled me aside and confided, “Yes, it’s wrong, but it is not an unusual practice.”

Unfortunately for the Westin and its customers, the contention for their overbooked rooms was unusually high that night — and all the other hotels in the downtown area were fully occupied, leaving them with the poor option of bussing people to a motel an hour outside the city. How could that be? They failed to accurately predict the demand from an event that was outside their domain of expertise, a rapidly growing Content Marketing World.

This was a customer experience black swan.

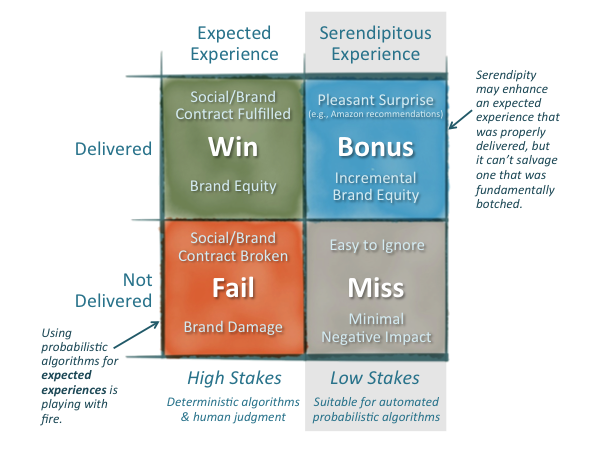

Here’s how something like that happens. Reserving rooms in a hotel is a ridiculously simple algorithm — if you deterministically never take more reservations for a given day than you have guaranteed rooms available. But since some travelers may not show up, the possibly exists for you to optimize additional revenue by overbooking rooms. If typically 5% of your reservations fail to show up, you could theoretically book 105% of your capacity.

That’s a classic insight that predictive analytics can deliver. But it’s also the point where you shift from a deterministic booking algorithm to a probabilistic one.

You’ve now consciously turned your customer experience over to the laws of probability — and there’s a chance that you’ll roll snake eyes with the dice and have a black swan event that significantly damages your brand. You may think it’s worth occasionally sacrificing the happiness of individual customers for that extra revenue from overbooking. But in world of search and social media, there’s a risk that you will trigger outsized negative consequences.

A hotel has three choices (which you can extrapolate to other businesses too):

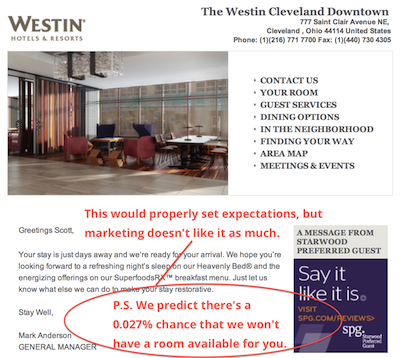

#1. Take the risk. Overbook your property, while still communicating to customers in your website and email a false guarantee. That works, until suddenly it doesn’t. Let me be blunt: this is lying, and you may pay a steep price for it someday.

#2. Don’t take the risk. Don’t overbook your hotel. Sure, you give up some potential short-term overbooking revenue, but you’re exchanging that for brand equity and customer loyalty. Factor this into your rates, or shift the risk to people making reservations with stricter deposit policies.

#3. Overbook and acknowledge it up front. Be transparent about the fact that a room isn’t guaranteed. Or, have two different rates and let customers choose: a cheaper rate for those who are more budget conscious and are willing to take a small risk; and a more expensive rate for those who value the guaranteed room more, such as business travelers with tight appointment schedules.

The folks at the Westin asked me what they could do to “make things right with me.” I don’t want points. I don’t want free nights. I don’t want a gift basket. Frankly, I bristle at squeaky-wheels-get-the-grease tactics. Instead, I want them to stop doing #1 (overbooking while pretending rooms are guaranteed) and adopt either #2 (don’t overbook) or #3 (disclose your overbooking openly).

Of course, changing policy and fixing marketing and operations alignment is much harder than just comping someone a room, so I suspect this won’t happen — at least not until more instances like this register on an executive’s Richter scale.

But in the meantime, it serves as a crystalline example of the dangers that predictive analytics can have when they’re used to risk expected customer experiences — that will hopefully help other businesses make better choices.

Scott,

Nice to see the effup you experienced at the Westin turned around into an insightful and useful marketing post.

Most business travelers have experienced something similar at one point or another.

In my case, I found myself “bumped” off a flight from LA to Sydney, (cattle class) but the restitution I was “persuaded” to accept was Business to Hawaii, with a plane swap, then 1st class to Sydney, getting in 2 hours later than my originally confirmed flight.

Same marketing lesson, but sometimes the restitution works out OK

This post shows that if content marketers started running hotels, hotels would be bankrupt soon. Westin is doing yield management and it makes perfect commercial sense to take the risk of a few dissatisfied guests vs having empty rooms.

If you’re leaping to the conclusion that I’m a content marketer, I suppose I should leap to the conclusion that you’re not a chief customer officer?

I have no problem with hotels running yield management. I do have a problem with them promising me something is guaranteed when, in fact, they’re consciously breaking that promise. Disclaim that the room is not guaranteed at time of sale and in the subsequent receipts sent via email.

Note that there are also many different kinds of yield management — for instance, dynamic pricing and segmented pricing. In fact, I’m all in favor of them applying segmented pricing to charge more to people who want a truly guaranteed room (or other ways of securing that money, such as pre-payment).

If you have to consciously lie to your customers to be commercially viable, I think you have a real failure of imagination when it comes to business models.

Well said.

Hey Scott – your point is well made, (and I’ve had similar experiences) but I think your conclusion is a little off target. The issue here is not that predictive analytics failed to provide the insights, but that no-one was monitoring the analytics and adjusting the business impact of them. I see this a lot – oh, we built a model last year and now we’re getting some weird customer behaviour. Duh, of course you are! Organizations cannot just build a model, publish it and forget it – that simply won’t cut it, as you have discovered. In your case, a 105% overbooking rate should have been throttled back to, say 102% because of an exceptional event which drove higher than normal demand. And the following week, the overbooking rate could be put back up again. I do think there are some organizations that take a cavalier attitude to modelling. It is not and never was, a silver bullet. Someone has to watch over it, like anything else that you use to run your business.

Cheers

Spot on. We have to remember that the models used to predict behavior are, in a way, reified patterns that we saw in the historical data; and that data is, itself, only a proxy for changing, fickle, emotional humans.

That said, a business built on algorithmic matching, where the algorithm is part of the offering – say, Amazon’s recommendations, or even Uber to some extent – can more easily succeed or experiment, and humans are apt to say “wow, that’s a weird recommendation”.

In either case, there is significant grey area to be aware of, where you need to be a bit more agile if you’re wading into. When your brand is built on human connection and emotional satisfaction, handing that brand promise completely over to the robots can be dangerous. You can easily lose customer empathy.

The other aspect that’s unspoken here is the trust factor. It takes a long time to build trust with your customer base, and only one incident to break it forever. Particularly in a scenario like hospitality for business travelers, where the customer is already in a stressful situation (having probably already dealt with the other group prone to using this same predictive equation, the airline industry). In the end, it just provides a big opportunity for someone else to step in, keep their word, and eat everyone’s lunch.

I guess it also depends on how well your brand is positioned and trusted. Trust is like your bank account savings: if you have a lot there then you could take the risk and ‘play with fire’ (think about Apple not delivering your new iPhone due to poor predictive algorithms, it just won’t damage brand image, right?). But if you’re the new kid on the block (poor trust/brand savings) you will actually play with fire, lava and kryptonite.

Westin sales dept. won here, as they booked every single room. Marketing dept. was ‘slightly injured’, as you may (should) share your bad experience through social, but CMT? Win? Lost? Unaware??

What do you think?

Cheers.

You might have a bit of a point in there, Neo (even though I fully concur with Scott’s response). Your point about yield optimization being a necessity of some form in that industry very well might be true. But that is only one side of this equation.

How can you argue that the risk of a few dissatisfied customers outweighs the extra few points of yield that are potentially going to be squeezed out? I doubt that you (or anyone) can measure that reliably. We’d need to consider risk/reward and cost/benefit. So in order to claim that yield optimization tactics like these are worth it (vs. having a few empty rooms), you’d need to balance them against the costs (including the cost of dissatisfied customers). The narrow view would be to attach a dollar figure to a customer and say they’re worth “x” and then run your cost/benefit analysis. The more appropriate view would be to consider that it’s more than a lost customer, it’s the effect that those customers have on your other potential or existing customers. That number very easily could outweigh the yield bump. Even if it didn’t, I think most reasonable people would argue that it’s bad business.

Since the ability to measure the risk/reward here is not a likely reality (it would require forecasting the cost of a bad reputation), we must resort to common sense. Clearly pissing off 5% of your customers is not something that would make it on a list of goals for your customer experience strategy, but by embracing this concept, that’s essentially what they’re saying.

Scott’s situation is a clear cut case of a bad faith agreement. They didn’t disclose the terms properly. Even if they did disclose it I’d still argue that it’s a shitty way to do business, but at least it would be a start. What they did is indefensible regardless of the economics of the hotel industry.

’nuff said, Scott already detailed out the case from just about every angle – even providing solutions for how they can maintain their yield without deceiving people. If you can’t see that, then I hope I never have to do business with the company you work for.

Good post Scott. I would love a choice #4. Give the dice to the Customer. Tell me that if I put down a non-refundable deposit at time of booking my room is guaranteed. If I don’t want to put down a deposit, I can cancel up until 6pm day of reservation, but there may be 0.027% chance that my room won’t be available. Complete transparency and I control my destiny.

Thanks, William. That does sounds like something that should be achievable as a reasonable business model to me.