“Bill Gates got it immediately. It took Andy Grove 10 years to figure it out, and 20 years for Steve Jobs.”

That quote in The New York Times by David B. Yoffie, Harvard strategy professor and co-author of a new book, Strategy Rules: Five Timeless Lessons from Bill Gates, Andy Grove, and Steve Jobs, immediately caught my eye. (Hat tip to M.G. Siegler.) What was “it” that these three titans of technology ultimately all figured out?

Platforms and ecosystems.

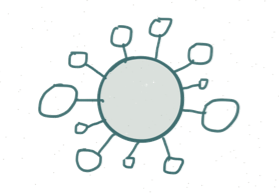

As the article explains, “In digital-age competition, the long goal is to establish an industry-spanning platform, rather than merely products. It’s platforms that yield the lucrative flywheel of network effects, complementary products and services and increasing returns. The payoff is market power and huge profits.”

The Windows operating system is the quintessential example of a “platform.” It was the critical mass of third-party developers, i.e. ISVs (independent software vendors), who made Windows the OS that everyone wanted, because it had the most software available for it. And because it was the most popular OS, software developers wanted to create their products on top of it. It was a virtuous cycle, and Microsoft dominated with it. Intel created a similar platform at a hardware level, and again, dominated their market.

Apple resisted that approach for a while. “Jobs was always a product first, platform second kind of guy,” the Times quotes Yoffie as saying. The article notes that Jobs “preferred beautifully designed products that worked in splendid isolation. But even he eventually grasped the value of platforms.”

A huge factor of the success of the iPhone and the iPad is their support for ISV-developed apps. The App Store has millions of these apps, which Apple now proudly touts. It’s no longer enough for a potential competitor to out-design or out-engineer Apple for an individual product — they’d have to overcome the incredible momentum of all those third-party apps.

That’s the power of platforms. In the book, Yoffie and his co-author Michael Cusumano — a professor at MIT who is an expert on software strategy and business models — note that a new generation of tech titans, including Larry Page of Google, Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, and Huateng Ma of Tencent, are also thriving through platform thinking.

You know who they don’t include as an example of platform success?

Any of the major marketing technology companies. Hmmm.

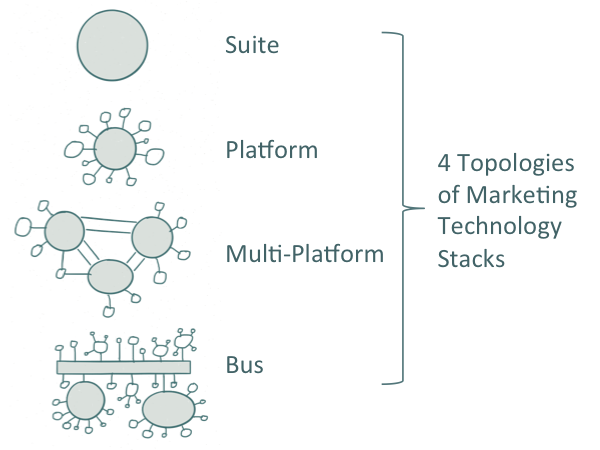

The Evolutionary Effects of Weak Marketing Technology Platforms

When marketing technology began to take shape as a potential market at the beginning of this century, many of the large enterprise software players pursued a strategy of a closed “suite.” The idea was to offer a solution from single vendor that did everything marketers would need — all perfectly integrated, perfectly controlled. You can imagine Steve Jobs from an earlier era, proud of his pristine product, unsullied by outside developers.

Unfortunately, the scope of marketing exploded at such a phenomenal pace over the past decade — a kaleidoscope of fragmentation, innovation, and differentiation — that it became impossible for any one company to do everything that marketers wanted or needed.

Observing those dynamics in my marketing technology landscape, I strongly encouraged the leading vendors to shift to more of an open “platform” strategy. I believed that there was an incredible opportunity for one or a few of them to create the equivalent of Windows-like or iOS-like ecosystems that would deliver tremendous value to marketers, marketing technology ISVs, and, most of all, those platform companies.

The results have been mixed. Salesforce played the platform card early — and at least within the CRM space, it has had the largest market share (18.6% as of last year). Marketo made a big public commitment to being a marketing platform and has probably the largest ISV community within its LaunchPoint partner program. Oracle Eloqua, Adobe, Salesforce ExactTarget, HubSpot, IBM, Act-On and others have all made moves to provide APIs to third-party developers and, in some cases, even an app-store-like marketplace for ISV products.

But for many, it seems like platformization has remained a secondary objective. In some cases, their APIs are rather limited. In other cases, there’s no real “marketplace” where ISV products are promoted. Many have been highly ambiguous about what would be in their platforms and what would be white space for ISVs. And in almost all cases, their platform-ness is far from the centerpiece of their marketing strategy. Most still emphasize everything that they do in their own product portfolio — support for ISVs products or “integrations” is treated as peripheral to their primary positioning.

Maybe they have good reasons for this. I suspect many believe that since marketers crave simplicity in such a complex world that de-emphasizing ISV products is a way of simplifying their value proposition. Many of their salespeople, especially at enterprise-class companies, have their hands full talking about their own products — they don’t want to distract buyers by bringing up other vendors, even synergisitic ISVs.

Whatever the reason, the result has been that while many of these are platforms, they are weak platforms. Don’t get me wrong — they’re certainly powerful systems. By “weak,” I just mean that they don’t have the same dominant kind of network effects that we’ve seen with Windows or iOS. Most marketers think of them as products, not platforms.

Ironically, I believe this has created more complexity in the market.

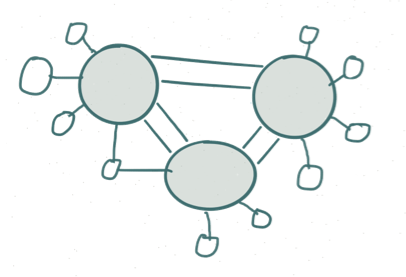

In the absence of an oligopoly of strong platforms as the foundation of marketing technology, we’re now seeing the rise of multiple specialist platforms.

Look at the marketing technology stack of a major company, and you’ll often see three or more “platforms” in their environment:

- a CRM platform

- a marketing automation platform (MAP)

- a web experience platform and/or e-commerce platform

- a social relationship management platform

- a data management platform supporting adtech

When you look at the investment strategies of leading marketing technology venture capitalists, they clearly seem to believe that there’s room for multiple multi-billion dollar specialist platforms within the marketeing domain. Social relationship platforms (SRPs) seem to be the hottest example of this at the moment. Sales enablement — or more broadly, ways of bridging marketing and sales — is emerging as another hot area of platform-thinking.

As this gains momentum — and, in particular, as these specialist platforms develop their own ISV ecosystems — it will be increasingly difficult for a single master platform to dominate. Even if a major enterprise acquires a bunch of these mini-platforms, the work required to synthesize them into a single, cohesive platform will be daunting. It’s possible that may happen in time. But on the visible horizon, enterprise marketing environments are looking more and more like multi-hub-and-spoke topologies.

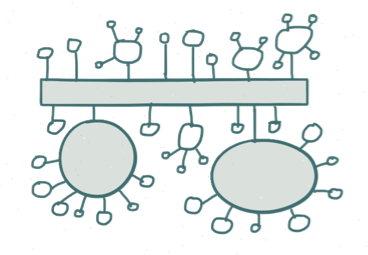

A similar, but slightly different model, is arguably an even more open “bus” architecture. Tag management companies like Tealium, Ensighten, and Signal, as well as enterprise service bus (ESB) companies such as Mulesoft, are championing this approach. These companies are specializing in manging the flow of data across multiple platforms and stand-alone products. The difference between a bus and a platform is subtle, but I’d say that the bus model is distinguished by its primary emphasis being on that flow across heterogeneous components in a marketing stack, rather than its own marketing execution capabilities.

Some customer data platform (CDP) companies — as defined by David Raab — also feel like they’re as much a bus as they are a platform.

I believe that the emergence of these multi-platform and bus topologies in marketing technology is a logical result of weak platforms. In the absence of a solid center of gravity for marketing innovation, these other models have been given the evolutionary opportunity to flourish. And now that the genie is out of the bottle, I think it’s going to be difficult to cork it back in.

However, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The absence of a strong platform oligopoly gives more market power to the buyers of marketing technology — and to the innovators of new marketing software. Strong platforms have many benefits, but they are a lot like benevolent (or not so benevolent) dictators. There’s a good reason why Microsoft was prosectued for anti-trust violations with their Windows platform.

Yes, multi-platform and bus topologies are a little more complicated. But in many ways, they are more flexible. And with marketing technologists increasingly a part of marketing teams, they’re becoming more manageable.

It will be fascinating to see where things go from here.

Get chiefmartec in your inbox

Join 42,000+ marketers and martech professionals who get my latest insights and analysis.