Last week, Microsoft announced that it was acquiring LinkedIn for a whopping $26.2 billion. This is the largest acqusition in Microsoft’s history — over three times the size of its acqusition of Skype for $8.5 billion in 2011 — and one of the largest in the history of the digital age (we’ll graciously look past that whole AOL acquiring TimeWarner fiasco).

I’d also claim that it’s the largest marketing technology acqusition ever.

If you skeptically raised one eyebrow with that last statement, you might be thinking, “Umm, LinkedIn isn’t really a marketing technology company.” But here are a few reasons why we can — and should — think of them that way:

- It’s the de facto platform that professionals across the business world use to market themselves to employers. I know, “personal branding” isn’t the same as brand branding — so you might argue that this isn’t really marketing so much as simply modern career management. But it’s not entirely dissimilar either, in spirit or tactic.

- It’s almost certainly the #1 social media platform for social selling — learning about individual prospects, networking within accounts, and identifying targeted referral opportunities. LinkedIn Sales Navigator is a great example of the company marketing this capability. You might protest that’s for sales, not marketing, but aren’t these two functions increasingly entwined in a digital world?

- LinkedIn has become a powerful distribution channel for content marketing — and a source of thought leadership on this subject too. Jason Miller, who was previously with Marketo, is now the global content marketing leader at the company and produces epic content marketing materials such as The Sophisticated Marketer’s Guide to Content Marketing.

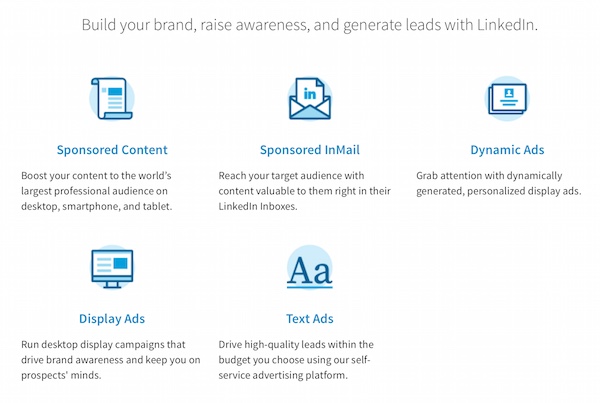

- Are the above points too indirect? Then consider that LinkedIn’s Marketing Solutions, which offers promtoional services to marketers such as sponsored content, sponsored InMail, display ads, text ads, and more. According to their 2015 financial results, Marketing Solutions revenue increased 20% year-over-year in the fourth quarter to $183 million and increased 28% to $581 million in 2015. It represents 19.4% of LinkedIn’s total revenue.

Now, you might argue that this doesn’t make LinkedIn significantly different than Facebook or Google, who also offer their own variations of the above to marketers too (although LinkedIn unquestionably dominates in the context of professional social media). Are all three of them marketing technology companies?

Actually, yes.

In fact, both Google and Facebook have been better positioned as marketing technology power players than LinkedIn — but Microsoft’s acqusition of the company changes that.

To explain why, we need to understand the concept of vertical competition.

Vertical Competition in Marketing’s Digital Channel

To appreciate why Google, Facebook, and — especially with this LinkedIn deal — Microsoft are possibly the most powerful martech companies in the world, we need to step back and look at the big picture of how marketers connect with prospects and customers in the digital age.

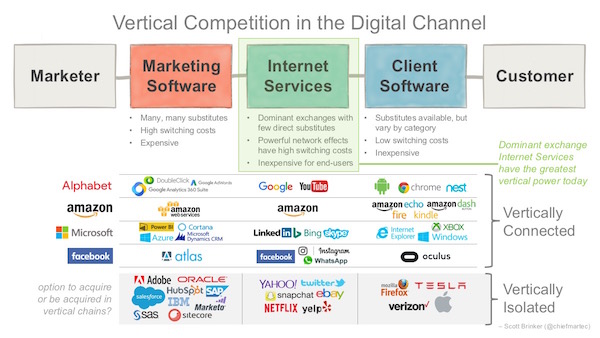

As shown in the illustration at the top of this post (click for a larger version), there is a “channel” of multiple different software stages (or layers) that marketers must work through to engage their audience:

- Marketing Software — the on-premise and SaaS applications that marketers buy and use to internally create and manage their campaigns, programs, and capabilities. The best known vendors in this space are companies like Adobe, HubSpot, IBM, Marketo, Oracle, and Salesforce, but there are thousands in the marketing technology landscape.

- Internet Services — the “destinations” on the web where millions of end-users converge, often as explicitly identified and authenticated subscribers. These include social media giants such as Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn, but also sites like Amazon, Google Search, Skype, and YouTube.

- Client Software — the devices, operating systems, browsers, and apps that end-users use to access the web and Internet Services. This includes desktop and laptop computers, smartphones, tablets, and increasingly new devices such as watches, TVs, smart home products such as Nest and Amazon Echo, virtual reality headsets, and even cars.

Interactions between marketers and customers must pass through at least two of these stages and very often all three. Each stage can set its own rules that govern how those interactions happen.

This results in two kinds of competition:

Horizontal competition among companies within the same stage of the channel. For instance, Adobe and Oracle are horizontal competitors in marketing software; Google Search and Bing are competitors in Internet services; and Google Android and Apple iOS are competitors in client software.

Vertical competition between companies at different stages of the channel. In vertical competition, Adobe competes with Facebook, and Google Search competes with Apple iPhones.

But what does that mean?

Vertical competitors, like all business competitors, ultimately compete for money, but it’s easier to recognize vertical competition on the web as a broader kind of “power.” In the digital pathway between marketers and consumers, who wields the most power in how those interactions are governed?

One way of assessing power is to consider what substitutes are available at each stage — the more alternatives you have and the easier it is to switch between them, the less power that stage has.

For instance, how easily can you switch between an Apple iPhone and a Google Android-powered smartphone? Pretty easily and inexpensively, with few adverse consequences. Will such a switch restrict your ability to access major Internet services like Facebook and LinkedIn? No. Although this varies somewhat by device — switching smart cars is a more expensive proposition — in general client software wields little power over consumers.

However, client software wields significant power over marketers, because they have near zero influence on which devices consumers choose to adopt. This effect is most evident with ad blocking features and plug-ins for web browsers. Marketers would certainly disable such things if they could. But they can’t.

Internet services are another matter entirely. Those that have become dominant exchanges — e.g., there’s enormous benefit to you being on LinkedIn and Facebook because everyone else you want to interact with is there too — are almost like monopolies. They demur by claiming that consumers don’t have to use their service and can switch at anytime. But thanks to the enormous power of network effects — with “winner takes all” dynamics — that’s not practical or likely. Therefore, this stage wields a lot of power over consumers.

But the leading Internet services hold even more power over marketers at this stage. Marketers have no choice: they must follow where their audiences go. Since Facebook, LinkedIn, Google Search, YouTube, etc. are the services that their prospects and customers turn to for information, entertainment, communication, and social networking, if marketers want to reach their audience there, they must play by the rules that these Internet services dictate. (And the behavioral data collected by Internet services makes every marketer drool.) Although most of these services make their money from marketers, their power is derived from their softly locked-in end-users — so they have far more influence over marketers than the other way around.

Then we have marketing software, most of which has no power over consumers. There are a few exceptions — software that helps marketers deliver good customer experiences via the web and other devices can have some power to attract and retain end-users. In those cases, marketing software is enabling a brand to essentially be its own, specialized Internet service. But for most marketing software, the consumer’s viewpoint is, “Don’t know, don’t care.”

Marketing software has more power over marketers, especially for larger or more expensive solutions where switching costs can be high. (As anyone who has switched marketing automation platforms at scale will attest.) But its power is limited by the incredibly intense horizontal competition in the marketing technology landscape. If you don’t like a particular marketing software vendor, you have many other alternatives to choose from.

You can appreciate the vertical competition between the stages of marketing software and Internet services by noting how all these marketing software giants are forced to continually adapt their software to changes imposed by Internet services. Facebook doesn’t care what Salesforce does. Salesforce cares a great deal about what Facebook does.

A few interesting cases of vertical competition in this channel to consider:

- Marketing software vendors who offer e-commerce platforms, such as Hybris (SAP) and Demandware (Salesforce), are essentially competing with Amazon to provide merchant marketers the best solution for selling products online.

- Marketing software vendors who offer products to manage search and social media advertising, like Marin Software and Wordstream, build on top of Facebook and Google — but they also compete with the direct advertising products offered by those services, such as Google AdWords and Facebook Atlas. Many tools that marketers rely on for their work might be shifted between these two stages of the channel — Internet services as “marketing-as-a-service” providers.

- Many Internet services, such as Facebook and LinkedIn, offer native apps as client software to compete with other client software, especially web browsers like Chrome, Firefox, Internet Explorer, or Safari. This gives them more control over the experience (including advertising!) and greater visibility into users’ client-side behaviors.

The last point of vertical competition is to bring it back to money: companies in each of these stages vie for a share of the marketer’s budget. They’re usually different line items in the budget, but they’re jockeying over slices from the same pie. Yet while that’s happening, they also serve as enablers for each other — hence why vertical competitors often consider each other “frenemies.”

The 4 (or 5) Horsemen of the Vertically-Connected Digital Channel

With that idea of vertical competition in mind, we now have a strategic framework to recognize that the most powerful companies in marketing’s digital channel are arguably those who are fully vertically connected — they have strong positions in all stages: marketing software, Internet services, and client software.

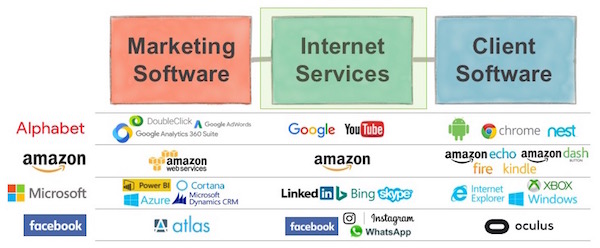

Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook are the leading examples of this:

Apple should probably be in this list too. Today, they’re primarily dominant in client software, but they also have Internet services for music and video, and they touch marketing software with iAds. However, since those two stages are restricted to users of their client software, that significantly limits their sphere of influence, at least today.

The potential of a vertically-connected ecosystem in the digital channel is what makes Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn so powerful. Although Microsoft has already had positions in all three stages of this channel, their primary strength was in client software (Windows, Xbox, Internet Explorer) and their secondary strength was in marketing software (Dynamics CRM, Office, Cortana). Their Internet services were a distant third, as Bing struggled against Google Search. They had no dominant exchange social media property.

Acquiring LinkedIn changes that. It will give Microsoft a very strong Internet service that is the dominant exchange of professional social networking. They will have star offerings in all three stages.

So what are the advantages of owning a vertically connected ecosystem? Here are a few:

- The relative redistribution of marketing spend across the different stages of the channel matters less if you’re earning revenue from all of them — in other words, vertical competition within your portfolio doesn’t harm you.

- You can leverage your products in one stage to boost the reach and value of your products in other stages (some regulation may apply). For instance, commentators have already noted that there could be excellent tie-ins between Office and LinkedIn, such as easier or more sophisticated publishing.

- The end-to-end visibility of prospects and customers across their client software, your Internet services, and marketers’ engagements with them through marketing software offers a much richer picture of customer insights. Yes, privacy issues will constrain this. But even anonymized and aggregate research data across the entire channel could be an amazing source of proprietary knowledge — and I wouldn’t underestimate the future of permission-based cooperation across the channel.

Microsoft’s toughest competitor in this vertically-connected channel is likely to be Google, which has had both dominant Internet services and client software for a while — and increasingly offers pure marketing software, such as with Google Analytics 360 Suite, which contains analytics, attribution, tag management, testing, personalization, a DMP, and more.

Microsoft could probably use greater strength in the marketing software stage of the channel as well — which is why they were rumored to be interested in acquiring Salesforce last year and Marketo this year. I think something like that will happen eventually. (As an aside, I think Satya Nadella’s Microsoft might be a better cultural fit for HubSpot than the firm was in the Ballmer years.)

For all these reasons, LinkedIn becomes a strategic crown jewel for Microsoft — and makes this the largest martech acqusition in history.

The vertically-connected marketing technology wars have begun.

P.S. By the way, I did predict that Microsoft would make a major marketing technology investment, albeit a year too early, in 2015. My not-quite-predictions for 2016 also suggested that vertical competition, as described above, would be an intensifying battle in digital marketing. My crystal ball was a little foggy, but can I at least chalk up a point or two?

Excellent article Scott. This acquisition is definitelly a big one not only in terms of money. I hope it will rather benefit LinkedIn services than slow it down. I loved the LinkedIn vision (ref Jeff Weiner Economy Graph movie) and development it did in last years. I noticed quite a decline in development of Yammer or Skype after MS bought them.

Great post (as always), Scott. Vertical integration also implies the least choice for customers at each stage (think: Apple, Henry Ford, or Standard Oil), and thus high monopoly profits. So it’s always in buyers’ interests to foster openness. It also makes it harder for non-integrated independents to survive — raising still more questions about the long-term viability of stand-alone marketing products, especially those that want to be platforms rather than plug-ins.

Incidentally, is it just me or do your diagrams show vertical integration on the horizontal dimension, and vice versa?

So then I have to believe that Twitter will be subsumed by IBM with a Watson-underpinning.

One other observation…I thought LNKD would acquire MKTO to create a great match between the social/data component and the software component, so I was surprised to see MKTO take the private route leaving them vulnerable to more powerful players.

Having said that, MSFT still does not have a marketing software component to compete effectively with Oracle and SFDC, so a LNKD acquisition without a strong marketing software platform still leaves a MSFT marketing cloud more like a marketing fog. With MKTO out of the way, Act-On looks like a great choice for MSFT to complete the vertical chain.