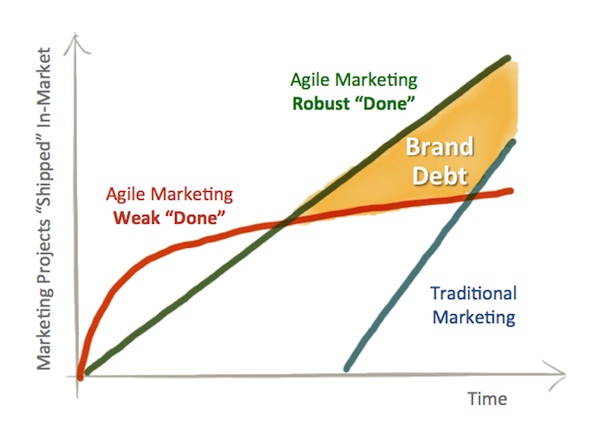

Agile marketing is often celebrated for speed — empowering marketing teams to get more ideas out into the market faster. But while that is often a valuable side benefit, it’s not one of the key principles behind agile marketing. In fact, putting too much emphasis on speed can be detrimental to marketing’s larger mission.

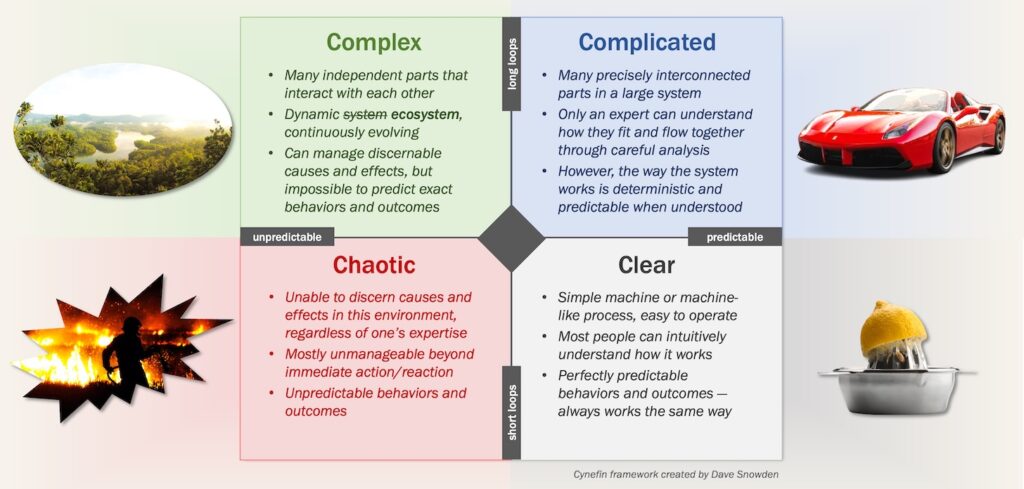

The heart of agile marketing is really its adaptability. By breaking ideas into small pieces and using short work cycles to iterate and re-prioritize those ideas every couple of weeks, marketing becomes extremely responsive to customer needs and market opportunities. Each iterative step becomes an opportunity to get feedback, measure impact, and optionally shift in a different direction.

The effect of this is usually a much higher velocity of ideas into market, because the scope of iterations are kept as small as possible while still being meaningful. Often small number of iterations — maybe even just one — ends up being sufficient. Rather than being stuck on a long haul, marketers can nimbly tap 80% of the value for 20% of the work for many ideas. And then quickly move on to the next most attractive opportunity.

But that caveat about iterations “still being meaningful” is important.

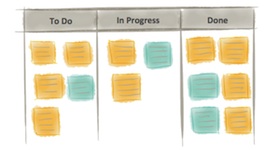

A typical agile marketing task board has three columns of tasks (or “stories”): the “to do” backlog, the “in progress” set of work that people are currently doing, and the “done” column for the tasks completed in that work cycle. Some agile teams will use additional columns for approval or validation of tasks before they are moved to done.

But problems can arise in the definition of “done.” It’s a highly subjective label. Different teams — and more problematically, different members on a team — may have different opinions for when something should be considered done, as a function of quality or completeness.

Let’s say there’s a marketing task to write an article on a particular subject. There are many different qualitative properties that the complete article can have. The writing can be better or worse. The way it ties into the rest of the company’s content can vary tremendously. Its SEO characteristics can be shaped in many different ways. Are there accompanying graphics? How good are they? And so on.

Teams should openly discuss what constitutes something being “done,” especially in the planning stage of a new sprint. But the fact is that many marketing tasks have inherently qualitative dimensions that defy a purely objective definition of done.

There must be a balance between avoiding excessive perfectionism — that perpetually stalls shipping things into the real world — and avoiding sloppy work in a rush to pile things into the “done” column. Different organizations and different teams will choose different points along that continuum, varying the placement of the fulcrum for different kinds of projects. But be wary of the extremes in both directions.

Moving a task into the “done” column is very satisfying. Particularly if you’re using actual Post-It notes or index cards, there’s a real tactile gratification. There can be considerable pressure, both internal and external to the team, to rack up done tasks. But unchecked, this dynamic can lead to a quantity over quality mentality. And in marketing, that almost always spells trouble for the brand.

Software incurs technical debt, marketing incurs “brand debt”

This challenge of defining “done” isn’t unique to marketing.

In agile software development, from which agile methods first emerged, there is wide recognition of the concept of “technical debt.” Technical debt consists of all the things that engineers know should be addressed with a particular feature — documentation, unit tests, refactoring to make the code more maintainable, etc. — that occasionally get postponed in the interest of getting a feature into production more quickly. A task may be “done,” but have achieved that by incurring some debt.

In small doses, to facilitate short-term goals, that’s fine. But unless the team circles back to pay off that debt, it can accumulate with interest. Eventually, unpaid debt will overwhelm a project, dragging down further progress in a quagmire of spaghetti code or other such cruft. A recent article on TechCrunch, Technical Debt Will Kill You Dead (If You Let It), sums up the danger well.

In agile marketing, the equivalent is “brand debt.”

Brand debt can consist of additional work around marketing deliverables, such as making sure new assets are properly added to a digital asset management repository, documented on an internal wiki, promoted to internal stakeholders such as sales, connected with references in other content and distribution points, and so on. With marketing technology, brand debt may involve technical fixes or updates that should be deployed.

But more often, brand debt is incurred by producing lower quality work, often in the interest of speed. Something is rushed to be done, perhaps due to an external deadline, a push to beat a competitor to the punch, or a time-sensitive opportunity (very common in social media). Maybe it’s for the first iteration of an idea that is going to be tested at a very small scale to see if it has any traction — the marketing equivalent of a prototype — with the intention that it will be polished in future iterations if the initial reaction is positive.

A little brand debt isn’t the end of the world. Brands have a certain amount of elasticity — some more than others — which permits some flexibility in how much quality is invested in a particular task. This can be quite helpful in cases where marketing wants to dip its toe in the water to try something. But if the quality slips too much, or if there are too many touchpoints of subpar quality, or too many of these trial balloons are left dangling out there, it can collectively take a toll on your brand.

After all, anything that makes it into a customer’s experience, will have an impact on their perception of the brand. In the case of a small marketing experiment, that may affect a very limited number of people. But still for those people, it will affect them.

It comes back to finding the right balance between super-slow perfectionism and super-fast sloppiness. Wherever your brand sits in that spectrum, brand debt occurs when individual tasks are delivered that fall below your brand’s average quality. To pay off brand debt, you need to raise the quality of work that will persist in the market and deliver more quality experiences to customers to offset any subpar touchpoints that they experienced.

Note that brand debt can also be amassed at a terrible rate if you hire people who consistently do poor work.

If brand debt is left unpaid, and continues to cumulate, eventually a brand will go bankrupt. Like a quagmired software project trapped under a mountain of technical debt, bankrupt brands will find it nearly impossible to move forward with customers who have lost faith in them.

Craftsmanship (i.e., brand) — the missing value in the manifesto

When the original manifesto for agile software development was published in 2001, there were four key values stated as its foundation:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

While these values were certainly what was driving the emerging agile movement, what was missing was any declaration of quality of work. In fairness, many engineers had always prized quality in their work, so there wasn’t necessarily a need for revolution there.

When I started kicking around the idea of an agile marketing manifesto in 2010, I based it off of the original values of the agile software manifesto, but tailored for the context of marketing:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Responding to change over following a plan

- Intimate customer tribes over impersonal mass markets

- Testing and data over opinions and conventions

- Numerous small experiments over a few large bets

- Engagement and transparency over official posturing

Again, what was missing was any reference to quality or “brand” value. After all, the things nominated were challenging the status quo, seeking to upgrade marketing management for a new century. Brand stewardship was already prized by marketers, so there was no need to call it out as the basis for a revolution.

When a group of pioneering agile marketers met last summer to craft a more official agile manifesto, they didn’t explicitly address brand values either.

However, in 2008, Robert C. Martin — one of the original founders of the agile software development movement — proposed that a fifth value should be added to their manifesto:

- Craftsmanship over crap

He later amended that to be: craftsmanship over execution. Because as we discussed above, agile methods — left unchecked without any countervailing value — could be misconstrued to emphasize speed and quantity over quality. A growing faction of the software development community was uncomfortable with this and sought to explicitly underscore the value of craftsmanship in their work. They strongly believed that was not incompatible with the other values of agile development.

I believe the same kind of value should be embedded into the agile marketing manifesto:

- Consistent brand quality over speed and quantity of execution

As they say, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more. This is not incompatible with the other values of agile marketing. And while it’s not revolutionary, it’s an effective keel to make sure that agile marketing doesn’t capsize as it accelerates with the wind of short and iterative work cycles.

In other words, this value exists to minimize brand debt.

When it comes to the why and how of applying this value, I love this presentation by Velocity Partners in the UK — Crap. The Content Marketing Deluge. It eloquently makes the case for brand quality, even while executing in an environment such as content marketing that is ideally suited to agile marketing:

In other words, craftsmanship over crap.

Scott, as usual, great insight. A couple of thoughts: just as agile developers attach acceptance criteria to stories in order to ensure that there is some definition of “done”, agile marketers can do the same thing – a piece of content that doesn’t generate sufficient traffic, twitter mentions, etc. isn’t “done”. I think this helps somewhat with the quality piece. If done right, it’s also more measurable. On the concept of technical debt, many times this is less about producing crappy code and more about making a conscious decision to build something in a way that works for today, but isn’t scalable, performant or as easy to use as you know you need to make it for the long term. You make the conscious decision to incur the technical debt because time to market is more important than creating the perfect long term answer. There’s probably a corollary in marketing – doing something today that meets the conversion goals, the distribution metrics, etc. but long term hurts the brand image. Which comes back to your final point, which I agree with – consistent brand quality over speed of execution, and even over short term leads, revenue and other metrics. For example, a brand may use a bunch of “tricks” in their landing page copy that convert really well in the short term, but in the long term hurt the client’s trusted relationship with the brand. This kind of “crap” is stuff we should avoid in Agile Marketing.

Thanks, Jim!

Your scenario of a landing page that artificially boosts conversion rate at the expense of delivering a better overall customer experience is an excellent example of “brand debt.”

Interesting thought on whether something should be considered “done” after the performance metrics from the market (e.g., share counts in content marketing) prove it was well-received.

There’s something very important there, as such metrics are essential to a marketing idea becoming “validated.”

But I see “done” and “validated” as different stages. A content piece can be done, which means the production is complete and it’s released out into the world. Up until that point, it’s fully under marketing’s control. Once it’s released, however, the dynamics of what happens next are much more complex. For instance, how long does it take that content piece to be validated by audience reception?

Ultimately, market-validated marketing tasks are the real wins.

But we need some label to say that internal work is complete and ready to be deployed to the market to pursue such validation. Of course, we could use a different label for that stage, not just “done.” Deployed? Released? In-Market?

Regardless of what we call that stage of released-into-the-wild, the question of quality and brand debt still seems closely tied to the decision to release something that your audience will be exposed to and will shape their perception of your brand — whether it’s eventually validated or not.

What do you think?

I think you’re right, and that your distinction between done and validation is very useful. The only comment I’d make is that Done has such a strong, emotional component to it that validated doesn’t have. Almost makes me want to use done and done-done. 🙂

I like that. 🙂

Actually, in all seriousness, that brings up an aspect of the typical task board that has always nagged at me in the context of agile marketing.

The flow of the task board is very linear and generally one-way. But particularly once you add a validated or “done-done” stage — which I agree is an important distinction in agile marketing — there’s value to seeing some of these dynamics as a more cyclical flow.

You could move a task backwards. Or you could create a new task, inspired from the original one, which is simply a natural iteration. (Does the original task end up in a “not validated” category?) But that doesn’t feel like it visually captures the narrative of what’s actually happening.

As always, you inspire great food for thought!

Great analysis. I love the idea of Brand Debt.

Next stop: Brand Bankruptcy.

Thanks, Doug.

You guys were half the inspiration for this post. I loved — still love — your “Crap” slide deck on why quality-over-quantity is essential to a brand’s future with content marketing. Brilliant thinking, brilliant presentation.

When I later came across Robert Martin’s “Craftsmanship over crap” mantra for agile software development, the two pieces connected into the inspiration for this piece.

Whether you’re a marketer or a software engineer, there is great value in cherishing craftsmanship over crap. And that principle should be part of the foundation of agile management in both disciplines.

Scott, I love this post.

I know its a simple illustration and I’m reading into it more than I’m sure you intended, but it does spark some questions:

1) Why is traditional marketing the “border” for brand debt? Is there a debt, in the agile marketing (or SW) meaning, created by a traditional marketing approach? I would have answered “no.” if there is a debt here, it is a different type of debt, no?

2) Do you believe traditional marketing, following an longer delay to get started, catches up with robust agile marketing? Or does it, because of its inflexibility, start to taper over time, whereas robust agile marketing will taper less because it is able to continue moving towards high impact opportunities?

Great post, thank you for sharing. Definitely sparks more thoughts!

Thanks, Eric.

I actually riffed this graph from a similar graph that several agile development articles had been using, with “waterfall development” instead of “traditional marketing.”

My interpretation of it:

Agile methods generally “ship” ideas into market faster than traditional marketing, because with traditional marketing, planning and internal development is done in larger chunks than more iterative agile approaches. So that’s why there’s a delay in when that line starts to rise. But you’re right, traditional marketing could be done better/worse or slower/faster and incur the effects of brand debt too — but that’s not represented in this graph.

When agile marketing artificially rushes to get things “done” — at the expense of quality — or if they fail to follow up to complete related work, either one of those scenarios could generate brand debt. However, the way this is drawn, with the yellow shaded area, it really only emphasizes the latter as a source of debt. As I think about it, the space between the red and green lines earlier in time, before they cross over, should also be highlighted in yellow as that represents brand debt of the first kind (rushing things out prematurely).

I’ll definitely update the diagram for future use to reflect that.

Thank you!