We’re going to try something different here. Louis Gudema, the president of marketing consultancy revenue + associates, submitted a guest post to me with the contrarian (?) viewpoint that marketing technology is not as big of a market as some claim.

He mostly takes issue with the “market opportunity” stated in HubSpot’s recent S-1 filing — not to pick on HubSpot per se, but because their S-1 is the most recent attempt to frame the market to public investors.

I found his analysis interesting — but disagreed with some of his logic. After going back and forth in email, we decided to publish this as a point-counterpoint article to bring you into the debate. We’d love to hear what you think in the comments, and indeed, it’s quite possible that Louis and I will continue there as well.

Louis’ Point: The marketing tech market is smaller than claimed.

The marketing technology market is much smaller than HubSpot says. Much smaller.

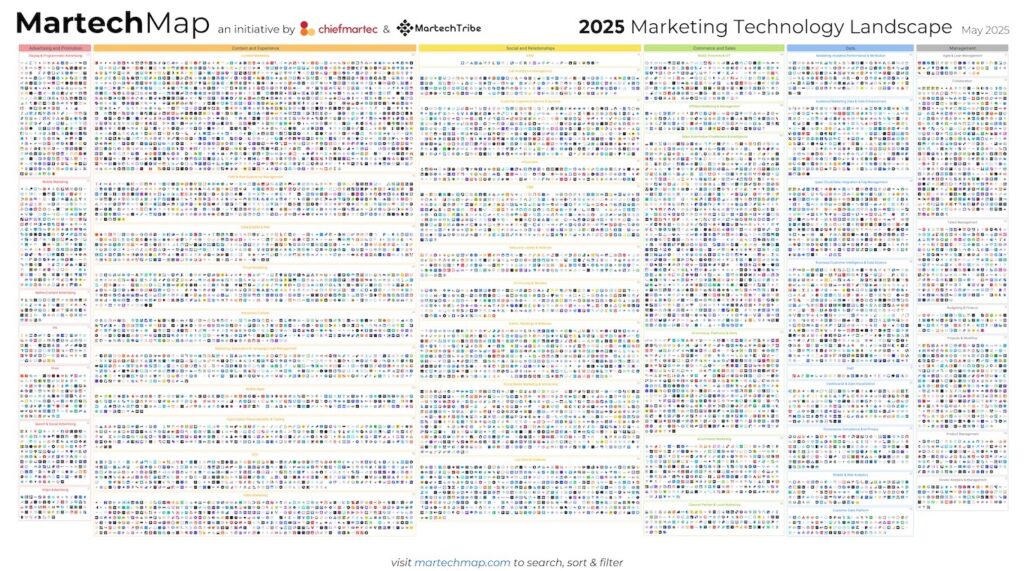

With ever better software tools, easy-to-scale cloud hosting, and countless incubators, the number of startups continues to accelerate. And many of them are creating marketing software. There are well over 1,000 companies providing marketing software today, and rising.

So if you’re in a company, or contemplating starting a company, which is developing, marketing and selling marketing technology, knowledge of the true size and state of the marketplace is indispensable for success. The HubSpot S-1 provides us an opportunity to consider these.

In its S-1 filing for its initial public offering, HubSpot defined a large market opportunity for its marketing software:

Businesses of nearly all sizes and in nearly all industries can benefit from delivering an inbound experience to attract, engage and delight their customers. We focus on selling our platform to mid-market businesses, which we define as businesses that have between 10 and 2,000 employees. As of June 30, 2014, we had 11,624 customers, and in the second quarter of 2014, our average subscription revenue per customer (on an annualized basis) was $8,823. According to AMI Partners, in 2013, there were 1.6 million of these mid-market businesses with a website presence in the United States and Canada and 1.3 million in Europe. According to a January 2014 study by Mintigo of 186,500 U.S.-based B2B companies of varying sizes, only 3% of those companies had implemented any of the most common marketing automation applications.

While that sounds impressive, if you parse the numbers in fact the real opportunity is far smaller. Let’s look at those supposed 1.6 million companies in the United States and Canada.

According to the United States Census figures released in December 2013 — which I’m putting more faith in than third-party estimates based on companies that have a “website presence”, which I guess is analyst-speak for “companies with a website” — there are actually 1,074,459 companies with 10 to 100 employees, 81,243 with 100-499 employees, and 17,671 with more than 500 employees. So the total number of companies with 10-2,000 employees in the U.S. is roughly 1.2 million. Canada’s population is about 11% of the U.S., so we could add another 135,000 or so companies for a total of around 1.3 million, rather than 1.6 million.

For a moment let’s focus on the lower end — the 592,963 U.S. companies with 10-20 employees (and another ~63,000 in Canada). The owners of about three-quarters of these companies don’t want to grow any larger. They may be small medical offices, contractors, a cupcake shop — a lifestyle business with an owner who is making enough money and doesn’t want the hours, headaches and risk of attempting to grow. So since they’re already at their optimal size, they’re unlikely to spend $8,000 a year for HubSpot, or any other marketing technology.

So that knocks about 490,000 companies out and we’re down to a potential market of around 810,000 — half of where we started — but we’re not done yet.

The reality is that many companies — maybe most companies — don’t need to market. Capitalism is an extraordinarily dynamic system and the variety of companies out there is astonishing. There are entire categories of companies that don’t market:

- Companies selling to markets with small numbers of potential customers. For example, “Our main business is providing airlines worldwide with operating leases on new aircraft delivering from our direct orders with Boeing, Airbus, Embraer, and ATR.” They don’t need to market, they just need a few phone numbers. Or “The Company is engaged principally in managing its owned mineral properties and the exploration for and the development of oil and natural gas properties.”

- Clinical stage biotech companies and companies in other industries in the product development phase; some of these will fail to develop a viable product, and others that do will sell their product to another company to market and sell.

- Real estate investment trusts and some other types of investment funds.

- And on and on.

The number of companies that don’t need to market is impossible to say, but having looked at hundreds of public and private companies as part of research into the adoption rate of marketing technology that I’ve been doing this year, I can say that it’s considerable.

Which then leads to my final — and most important — point: 20 years after the release of the first Mosaic browser, and 15 years after the release of the first marketing automation program, the adoption rate of marketing tech in most industries is still very low. Software companies themselves have a high adoption rate, but when you look at industries such as manufacturing, medical devices, and professional services such as engineering and architecture, the rates are shockingly low. HubSpot alludes to this with their reference to a Mintigo study saying that only 3% of companies have yet to adopt marketing automation; I assume they put that in to suggest that shows how large the untapped market still is. Sirius Decisions says that 16% of B2B companies have implemented marketing automation. I think that’s closer to the truth. In my broader study of marketing technology adoption by mid-market New England B2B companies it was 29%.

Whichever number you trust, the truth is that the adoption of most categories of marketing technology is progressing at the rate of just a couple percentage points a year.

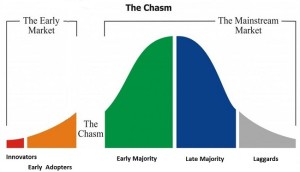

Tech companies want to find a way across Geoffrey Moore’s chasm into the mainstream market because that’s where the lower cost of sales and higher profits are supposed to be. But by now many marketing tech executives have enough experience to know which market segments are the most receptive to their offerings and so, of course, they point their initial sales efforts at those. As a result, instead of dropping their customer acquisition costs (CAC) can actually rise as they broaden into more market segments. HubSpot’s CAC has risen dramatically from $6,671 in 2011 to over $11,500 today. (Others have asked whether this calls into question the efficacy and scalability of HubSpot’s inbound marketing approach. I’d say no, because their sales and marketing efforts go well beyond inbound marketing and have included major investments in everything from Google AdWords to Facebook ads to tele-prospecting.)

So not only is the market less than half the size that HubSpot claims, although still considerable, but it is a skeptical market likely to have high customer acquisition costs.

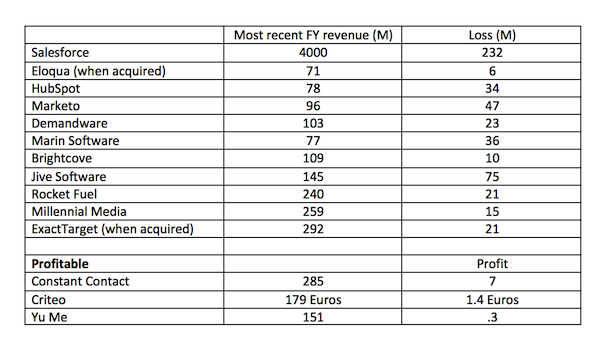

I say this not to whale on HubSpot. They’re certainly not alone. Many companies are struggling to make a profit from the creation and sale of marketing tech software; most of the public ones are losing money, in many cases lots of money. Even Salesforce, which offers one of the major “Marketing Clouds”, lost $232M on $4B in sales last year and says in its annual report, “We derive substantially all of our revenue from subscriptions to our CRM enterprise cloud computing application service, and we expect this will continue for the foreseeable future. The markets for our Salesforce1 ExactTarget Marketing Cloud and Salesforce1 Platform remain relatively new and it is uncertain whether our efforts will ever result in significant revenue for us.”

No, I say this to help shine light on the true size and state of the marketing tech market. I’m a big believer in martech. I know that, properly implemented, it can produce great ROI for companies and help drive faster revenue growth. But business is challenging — very challenging. And for companies operating in the marketing tech category there are especially difficult challenges. Having accurate market data is the first step toward dealing with them.

Scott’s Counterpoint: MarTech is bigger than that math suggests.

I like the analysis you’re doing — but I’m not sure I fully agree with your math either. A few of the counterarguments that come to mind:

1. $8,000/year is an average — but there could be a significant spread around that mean. Larger mid-sized companies might be spending tens of thousands per year, which counterbalances those spending less or nothing. And in the other direction, HubSpot (or other vendors targeting the “micro business” market) might have offerings for less than $100/month — that could then capture more net customers.

2. Given the entrepreneurial nature of many Internet-only based businesses, it wouldn’t surprise me if the U.S. census numbers underrepresent those. People who have a full-time job at a company, but then they’re running an e-commerce or consulting or software business on the side. Admittedly, most of those won’t be big, so they won’t be able to afford much software — but they’re also the kinds of people/businesses who are predisposed to buying software for their little ventures if the price/value equation works.

3. Even businesses that don’t want to grow, may not want to shrink. My father-in-law has been running a small materials handling business for 24 years, mostly just on his own, and was happy to keep it at the same size. Most of his business came from catalogs he would mail to a set of known clients. But in the past few years, those sales have dropped dramatically — those clients aren’t using catalogs, they’re turning to Google anytime they need a specific part. By not having much of an “inbound” presence for his business, he’s being shut out. Needless to say, he’s developing a much keener interest in the technology and investment to address this.

Louis’ Rebuttal: Yet low adoption rates are fact.

We could argue about which data to use, but I think the fundamental issue is that the adoption rate is low. As my research in mid-market companies showed, the bell curve is way over to the left at the low adoption end. And from my personal experience, and other data, I’m sure it’s even less in that huge part of the economy which is small businesses. According to Google, 55% of small businesses don’t even have a website.

Perhaps one way to think of this is that there are two types of companies: venture-backed or public ones and, for want of a better word, organic ones — companies that essentially are bootstrapped. (What would you call them? I don’t like the “lifestyle business” term.”)

Venture-backed/public martech companies are really struggling in the hyper-competitive world. Low adoption rates and huge losses, and the few profitable ones make very little. Some examples:

Organic companies may have a better shot at being profitable. In one of the comments to Tom Webster’s post about whether HubSpot’s financial performance is a referendum on inbound marketing, Brian Clark, the founder and CEO of Copyblogger, said, “At Copyblogger Media, we took a more purist content marketing approach. No VC or outside investment, no advertising, all audience-driven plus solid marketing and sales fundamentals. We’ve been profitable since day one and we’ll do about $10 million in revenue this year.”

So maybe the choice is between organic, slow, profitable growth with a small market share (even an organic company with 5,000-10,000+ profitable customers has a very small part of the market, whether the market is 800,000 companies are 1.6M or whatever). Those companies, though, may be vulnerable to bigger or venture-backed companies entering the space, Or, on the other hand, venture-backed moonshots. In either case, though, the use of the software is very low compared to how some other technologies (PCs, networks, office suites, email, etc.) that have swept the field.

But to briefly address your three points:

1. HubSpot has some customers (like me) that are only using their Sidekick (formerly Signals) email tracking, or other lower end services, but they don’t really have enterprise pricing, which is I think one of their major problems. And they can’t survive on lots of $100/month customers.

2. There may be many “hidden entrepreneurs”, but I don’t know that they’re significant. In any case there are SO many data points on low adoption rate it may not really matter. (Like that <50% of small companies even having a website.) 3. Sure, there is a slow increase in adoption, like with your father-in-law, but it's at the rate of a couple percentage points a year. There has been no explosion in the use of martech, unlike smartphones, search engines, and tablets, for example. I used to think of the Internet as this explosion (Amazon! Google! Facebook!), but over the past six months of diving into this I've come to think of the adoption of martech as being like the growth of rings on a tree.

Scott’s Rebuttal: Platforms are a long-game investment.

So my company, ion interactive, is an organic marketing technology company that’s also profitable with significant revenue. Organic ventures have to be profitable, by definition. And I’m the first to sing the praises of the fiscal and market discipline that running a good organic company requires. There are many benefits to this approach — so you’re singing to the choir there — although it’s not without challenges either.

However, I don’t think that inherently refutes or invalidates the choice of other venture-backed or public companies to raise a ton of money and operate at a loss for years. Surely none of them plan to run at a loss forever. They’re investing in the short-run to earn their return in the long-run.

There are many reasons companies make that choice. I believe such a strategy certainly suits a platform play: if you believe a market is going to ultimately come down to a small number of platforms — and I do mean true platforms that thrive on the ecosystems built around them — it’s to your advantage to grab as much market share as fast as you can. Even if you do so at a loss in the short-term. Because there can only be so many platforms in a market. If you can secure your company a position in the end-game oligopoly, you’ll be able to earn significant returns from that position for a long time to come.

To me, marketing backbone systems — like HubSpot, Salesforce, Oracle/Eloqua, Marketo — are in a race for just such a platform oligopoly. So I believe they’re doing the right thing by spending ahead of the revenue curve. It may not pan out for all of them (although M&A consolidation may still give investors good returns). But for some, they’ll end up sitting on a gold mine.

But let’s get back to market size.

I don’t believe the present size of the marketing technology market is an accurate reflection of what it will grow to become over the next 5-10 years. To the degree that most of the sales of these systems have been to Geoffrey Moore’s innovators and early adopters — as your study suggests — then the lion’s share of the area under that bell curve for the early majority, late majority, and laggards is still waiting to be captured. In growth opportunity, that’s a feature not a bug!

Of course, it’s only a feature if the majority adopts these marketing technologies in time. But I believe they will. Not because they like change or fancy marketing software. But because they will have to in order to serve the needs of their customers in a digital world — after all, this kind of marketing is broader than the classic “marketing department.” For instance, my father-in-law is not a marketer — but it matters tremendously that the way in which his customers want to interact with him has changed. Those who fail to keep up with customer expectations will eventually be replaced by new competitors who will seize the opportunity. I think that shake-up will accelerate in the years ahead.

At the same time, I would confidently bet that marketing technology companies will continue to expand their product portfolios, offering more capabilities to those who want them — with even more revenue potential — while also offering simpler, low-end solutions to those small businesses with minimal needs and budget.

I wouldn’t underestimate the potential profit that companies can earn by selling sub-$100/month products to a large number of people either — especially if those products have the attractive economics of self-service, cloud-based software. Some of those seeds can blossom nicely over time.

While I appreciate the cautionary points you’ve raised, I still believe that in the long run the market for marketing technology is at least as large as what’s represented in HubSpot’s S-1 — maybe even larger. It may take a number of years to realize that outcome, but that’s okay. Of course, I’m biased and bullish on this topic. But that doesn’t necessarily mean I’m wrong.

Readers — what do you think?

Some fascinating discussion here. Thanks for this, guys!

One point I’d add, though, is that some of the biggest software companies in the world are all betting against Louis’s analysis. The steady consolidation of the big marketing suites (Adobe, Oracle, IBM, SFDC) is based around a single premise: that “Martech” is an emerging software market segment, and while it’s not enormous, is growing steadily. It’ll continue to grow, rapidly, as new technologies further shift consumer behavior and force more companies to market and interact digitally. This has led to enormous investments in acquisitions.

Here’s a high-level breakdown of what those acquisition investments look like: http://www.bullishdata.com/tally-major-marketing-technology-acquisitions/

That said, I think Louis has a point here – there isn’t enough room in this market, now or in 5 years, for 1000s of martech vendors. Even in the enterprise space (where we, IBM, play), I don’t think there is sufficient opportunity for four or five major marketing vendors. SaaS and marketing are both inclined towards “winner take all” markets, and I think it’s much more likely that two or three major vendors will divide up the “enterprise” space in highly unequal ways. Gradually, the mid-market segment will consolidate in a similar fashion.

Thanks for sharing your perspective on this, Blair!

I agree with you almost entirely. Except I believe the consolidation will be among major marketing PLATFORMS — and those platforms will enable a very diverse ecosystem of hundreds or even thousands of specialized marketing software products on top of them.

There’s also a lot more software than the “big guns” of CRM, MAP, CMS:

https://chiefmartec.com/2014/09/marketers-frequently-use-100-software-programs/

But I suspect this may be fodder for an entirely separate point-counterpoint between us? 🙂

Good points, Blair and Scott. Who am I to argue with Larry Ellison? I agree the market will continue to grow, but it’ll be a long, slow slog for many companies. We’re not going to see a martech Candy Crush or WhatsApp, so people entering the market need to be prepared for that emotionally and financially.

And, like the early days of the auto industry, there will be many losers. But unlike the auto industry the barriers to entry are very low. As Peter Thiel said in a recent WSJ piece, “Under perfect competition, in the long run no company makes an economic profit.” Maybe those low barriers to entry make for perfect, martech competition, and little or no profits.

These may develop into platforms, but how many? And how profitable? Jack Welch says don’t go into a market if you can’t be #1 or #2. A lot more companies than that are vying for the brass ring here.

I don’t want to be a Debbie Downer, just a realist. Look at that chart of revenues and losses. With high operating margins SaaS companies were supposed to be wildly profitable. And look at those increasing CACs. Is that crossing the chasm or walking into a buzz saw? I am reminded of Marc Andreesen’s question in the early days of AOL: If 5 million users isn’t enough to be profitable, how many does it take? It turned out to be 8 million, just as Constant Contact needed 300,000 customers before getting into the black. And profits for AOL were short-lived and for Constant Contact small.

By a traditional business model only the organic approach makes sense, IMHO. The VC route is a roll of the dice.

Scott – so happy you provided the two perspectives. I have been thinking about HubSpot’s business claims for some time so its refreshing how transparency provides more light to the situation. The four issues that seem to stick out at me come from this excerpt.

“We focus on selling our platform to mid-market businesses, which we define as businesses that have between 10 and 2,000 employees. As of June 30, 2014, we had 11,624 customers, and in the second quarter of 2014, our average subscription revenue per customer (on an annualized basis) was $8,823.”

First point: Unless something dramatically happened to the mix of their portfolio of clients, only 12 months ago, their total number of “mid-market” clients represented about 2% of their total base. This speaks to the position in the market they have succeeded and will mostly like own – the SMBs of companies less that 50. They have struggled mightily to move upstream due to their sales model, but more to the fact their competition own the enterprise due to their vastly superior functionality to serve an enterprise.

Second: Given the CAC at $8K + and the lion share of small clients paying at the near lower levels of subscription, then something smells in Denmark.

Third: They have about 450 sales people. Doing some rough math, at an average comp of $75K per sales person, there is about $33M spent on sales people. And the remaining $20M is on (alleged inbound?) marketing. This seems like a fairly normal ratio of direct labor to marketing ratio. I would think the efficacy promise in action would have panned out by now.

Fourth: Isn’t “inbound marketing” a catch phrase for “pull” marketing within the context of the classic “push/pull” media mix?

Interesting points, Jeff. Unfortunately, I don’t have the data and/or haven’t done a deep enough analysis of HubSpot’s S-1 to be able to address the issues you raise.

I suspect someone from HubSpot might want to chime in to address these, but given that they’re in their quiet period, they probably won’t — even if they might wish to.

However, I do take their S-1 at face value. In this litigious age, I believe it’s not in their interest to intentionally misrepresent anything in there. Some of the data you’re raising isn’t data that’s in the S-1, so I’m not sure how much is fact and how much is folklore.

I also imagine that HubSpot is not representative of the companies they serve. Trying to get the world to change the way it thinks about marketing — creating this whole new “inbound” movement — is a bigger challenge than serving an existing market with an existing solution. I think of Marcus Sheridan’s success with River Pools as a more normal version of inbound economics. Whether Marcus is the exception or the rule though, I don’t have enough data to say.

Anyway, I’m getting outside of my depth of conviction. I believe very firmly that the marketing technology space is a huge growth market. The financial dynamics of individual firms within that space is a whole level beyond my expertise.

The photo of the counterpoint guy looks like a drunk version of the point guy.