One of the perennial criticisms of the martech landscape is that “most of these products all do the same thing.” Send an email. Render a web page. Analyze some data. This criticism has grown louder in proportion to the growth of the landscape.

With an increasingly exasperated tone, people ask, for example, “What’s the point of hundreds of CRMs or marketing automation tools? They’re all just storing the same customer fields and mail merging them into campaigns.”

I’ve generally had two opposite responses to that accusation.

First, I get a little defensive and say, “Hey, there are genuine innovations that happen in martech all the time. For instance, you can’t look at a product like DALL-E 2, that magically generates images from any description you can express in words, and not appreciate that, wow, this really is something new under the sun.”

But not all innovations in martech are that remarkable. Coming up with the first few reverse ETL tools to easily (re)hydrate data into your app stack from your data warehouses was super useful. But it wasn’t worthy of a headline in The New York Times.

So, my fallback response is to admit, “Yeah, I guess you’re right. All email marketing tools kinda do the same thing. But, hey, on the bright side, that sort of commoditized competition among vendors should be great for you as a marketer. Laws of economics: it should drive down your price.”

That often mollified those critics, who largely just wanted me to acquiesce to their gut-level belief that the martech landscape was all sound and fury signifying nothing. But it didn’t sit well with me. It didn’t seem to explain the sheer volume of variations of products in martech categories nor the enormous amount of intellectual capital that kept being invested in them.

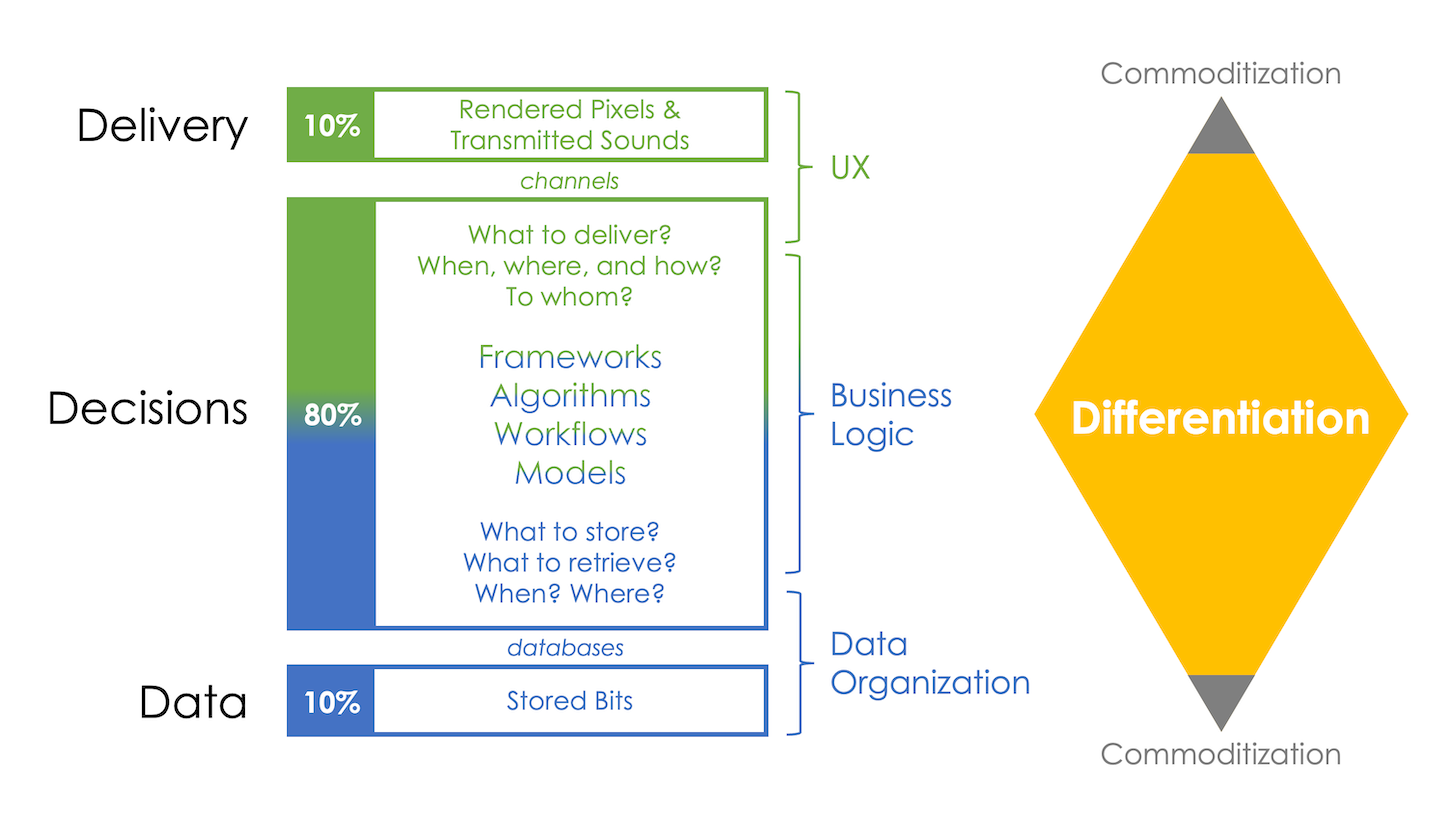

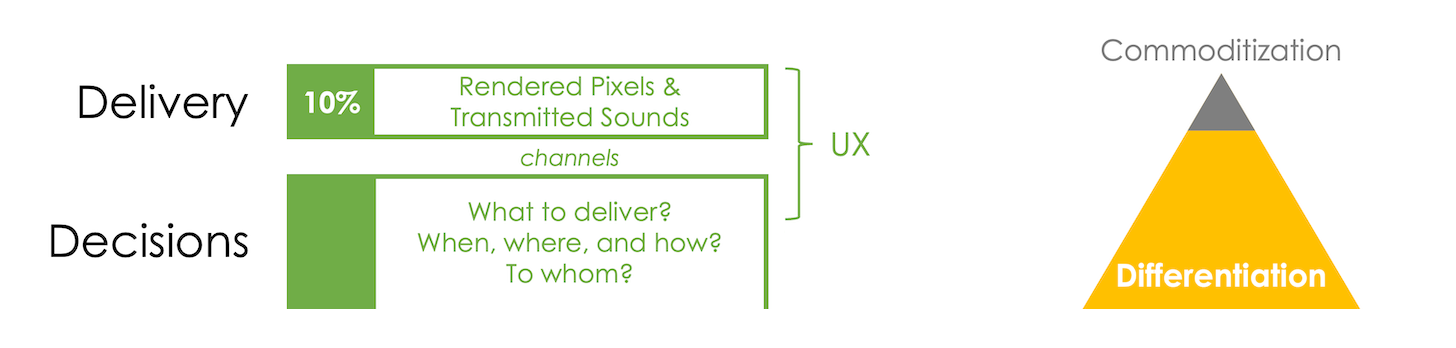

Three-Tier Architectures: Data, Decisions, Delivery

Let’s start by recognizing that most software follows a pattern of three tiers or layers:

- Data — at the bottom: records stored in a database

- Presentation — at the top: what appears on the screen to users

- Business Logic — in the middle: decisions and flow between the other two layers

David Raab, the inventor of the CDP category, mapped these to three stages of data, decisions, and delivery. (I wrote an article last year riffing on that model called Data, Decisioning, Delivery & Design to distinguish CDPs from cloud data warehouses, CDWs.)

But these three layers aren’t equal in scale or complexity.

The data layer seems intuitive as the simplest layer. If you’re talking about customer records, such as in CRM, there are usually a finite number of fields being stored. And the most important fields are always the same: name, company, title, email, phone number, address, etc.

Of course, all customer data isn’t entirely that homogenized. Different businesses collect different information around purchases, customer behaviors, demographic, firmographics, technographics, and so on. There can be relational data connecting those customers with campaigns, program, and partners.

However, the quantity and dispersion of variation is modest. In other words, the data layer is fairly susceptible to commoditization.

What about the presentation or delivery layer? Most people — especially UX professionals — would say there’s a lot more scale and complexity here. It’s everything that everyone sees or hears!

Intuitively, there’s enormous variation in presentation. Some interfaces are beautiful; others are ugly. Some show you exactly what you want, where you want it; others are a hot mess that your eyes painfully bushwhack through to find the one thing you were actually looking for.

So presentation is an area of differentiation, not commoditization, right?

Actually, no.

Forgive me for getting a bit philosophical here, but trust me, there’s a meaningful point to it.

The technical layer of presentation is actually fairly constrained. There are only so many pixels, of so many colors, that you can put on a screen. I’m not talking about what those pixels represent — that’s something different, which we’ll get to in a moment. The raw pixels and their common patterns veer towards commodities.

For that matter, if we expand beyond just “presentation” to cover other facets of “delivery” — how that presentation actually arrives in front of someone — that’s pretty commoditized too. The HTTPS protocol for web pages. The SMTP protocol for email. The SMPP protocol for text messages. These aren’t just commodities, they’re standards.

Now before designers start sending me anatomically unflattering wireframes of where I can stick this post, let me quickly follow up that design and UX are incredibly complex and important facets of products and experiences that offer tremendous opportunity for differentiation. (Look, I even put it in bold!)

But the magic and mastery of design and UX isn’t in the delivery. It’s in the decisions about what to deliver — when, where, how, to whom.

It’s the decisions in UX that create differentiation.

Decisions Are the Wellspring of Differentiation

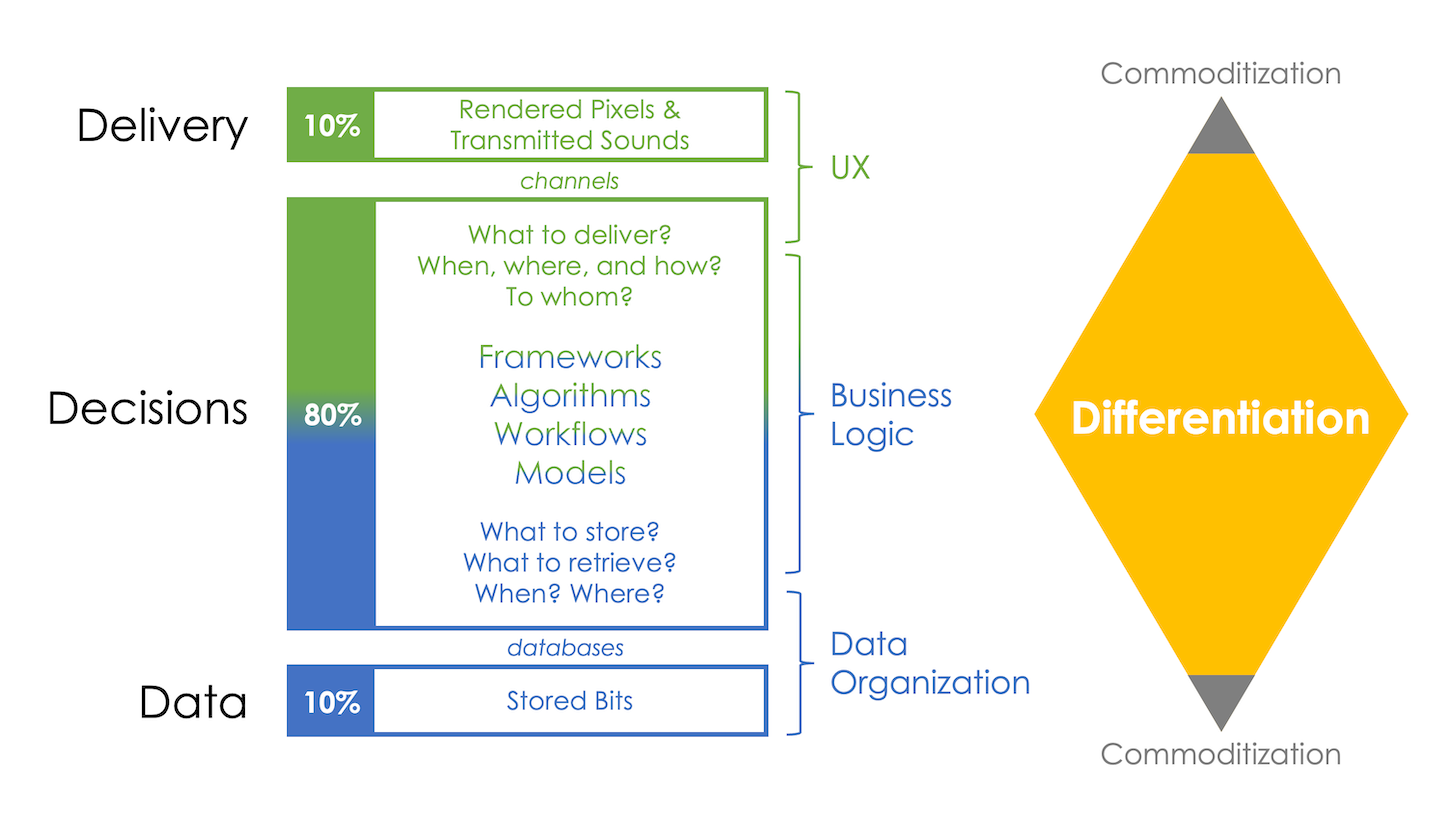

Most of software is decisioning. All those instructions running through processors deciding if this, then that, millions of times per minute. The majority of code in applications is “business logic”, a vast ocean between the seabed of common data and the relatively thin waves of presentation delivered on the surface.

The scale of the decisions layer in software is massive. I’ve drawn it as 80%, relative to 10% for data and 10% for delivery, in my diagram. But it’s probably closer to 98% vs. 1% and 1% in most applications.

It’s also complex. And I mean “complex” in the scientific sense of many interacting parts — and not just isolated within that one program itself. The decisions one software app makes are affected by the decisions other connected software apps make. In a stack of dozens of apps, hundreds of data sources, and thousands or millions of users, all feeding different inputs into a program’s decision-making, you have an astronomical set of possibilities.

It’s in this complex environment where different software apps bring to bear different algorithms, frameworks, workflows, and models to make decisions in different ways.

There are three important points about this decisions layer:

- It’s the largest portion of what composes a software app.

- Collectively, there’s a near infinite number of different possible decisions.

- These decisions can have significant, material impact on business outcomes.

The last point should be self-evident. Businesses compete on the decisions they make. If you don’t think you can make different — better — decisions than your competitors, you should probably consider a career as a hermetic monk. (Ironically, a very differentiated decision to make.)

The decisions layer in software is a massive canvas for differentiation. And with its potential impact on outcomes, it’s a massive canvas for meaningful differentiation.

Almost no two software apps — at least apps of any significant size — are the same.

Martech: Commoditized and Differentiated

When you look at the high-level categories of the martech landscape, such as a big bucket for CRM, with hundreds of logos, it’s fair to say that, sure, in some broad sense, all those apps are the same. They are all for customer relationship management.

You could also rightfully say that the data stored in those CRMs are generally quite similar too. As are the delivery channels in which they serve up presentation to employees back-stage and customers front-stage. Through those lenses, they are commoditized products.

But the gigantic mass of decisions within each of these different CRMs varies tremendously.

Spend some time using HubSpot (disclosure: where I work), Microsoft Dynamics, and Salesforce, and you will appreciate just how different these CRMs are. Certainly for your experience as a user. But from the myriad of things that contribute to differentiated experience for you in those CRMs springs a fount of different business decisions and customer interactions.

Is one obviously better than the others? (I’ll resist my personal bias in answering that.) Given the wide adoption of all three, you have to conclude that the answer to that question is different for different businesses.

(Yes, it’s a meta-decision to decide which decisions bundled in a CRM platform you prefer, to help you make better decisions for your customers, to then help them make better decisions in their businesses, and so on. Turtles all the way down? Nope, it’s decisions all the way down.)

And it’s not just those three CRMs. It’s the hundreds of others. Each one developed by different people bringing different ideas, philosophies, frameworks, and implementation choices to the huge number of decisions embedded in their product. All of which ripple into differences for how your business will actually operate in zillions of tiny ways… but which aggregate into not-so-tiny differences.

More colloquially, this is called opinionated software.

Now, not all those differences will be good ones. It’s a Darwinian market for sure. Some CRM platforms will thrive; others will go extinct. New CRM startups will sprout with new variations. Over time, there may be more or fewer. But there’s space for different CRMs with different decision layers to legitimately exist, as long as each one has a customer base — even if, or maybe especially if, it’s a niche — who prefer the unique decisions of that vendor.

This dynamic is present across all categories in martech.

Incremental Innovation Is Still Innovation

Now, are the differences in the decisions layer between two martech products in the same category breakthrough, leap-frogging innovations?

Admittedly, most of the time, no. They’re more often “incremental innovation” — finding better ways to do something, not so much creating entirely new somethings. But it would be a mistake to disdain, “Pffft, that’s only incremental innovation.”

Incremental innovation is still innovation. It can meaningfully differentiate one vendor from another and deliver great benefits to their customers.

This why martech has 10,000 products that all kinda do the same thing — but not really.