Martech software companies — and SaaS vendors in general — have several different ways they can charge for their products.

The classic SaaS subscription models have used seat-based and tier-based pricing. As a buyer, you pay for the number of people (“seats”) using the product in your company. Or, you pay for bundles of functionality offered in “tiers” — with more features included at higher-priced tiers.

Or both: you pay for seats, but the price per seat goes up for higher tier subscriptions.

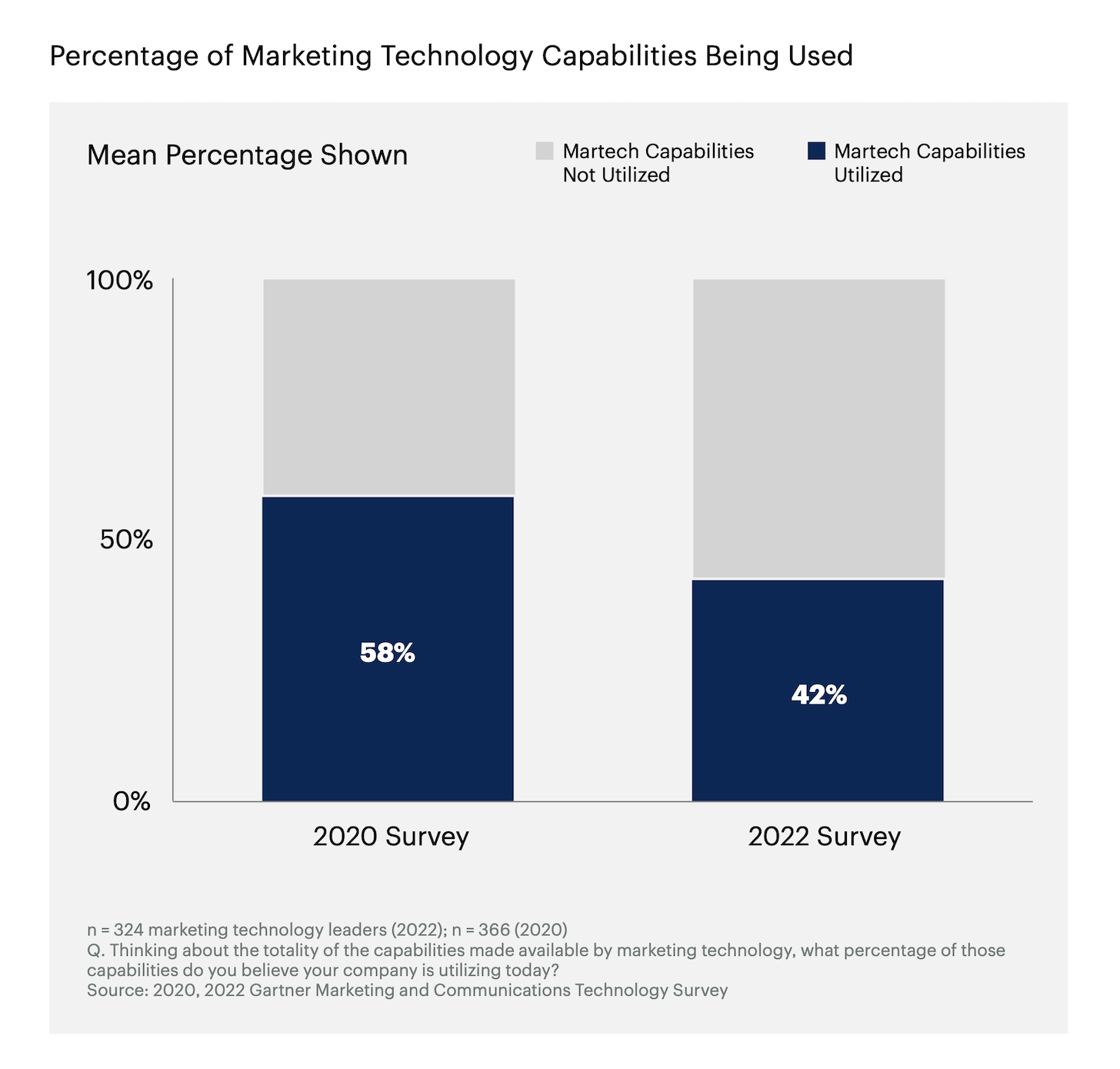

Overall, these models have worked well for the past couple of decades. But they have their challenges. The biggest is “utilization” — which functionality individual users use and how much they use them. The problems here cut both ways.

Buyers complain that not all their users use all the features bundled into their seats or tiers. They look at that unused functionality as “waste” that they’re overpaying for. Frankly, I’ve always thought this was a misguided way of calculating value from software. But I’m in the minority on that opinion.

Gartner’s been tracking this buyer’s view of martech utilization for a few years, and it’s been dropping. How could it not? Software vendors often add features faster than most of their users can adopt them (hello, Martec’s Law.) And this exacerbates the perception of underutilization.

But utilization in seat-based/tier-based subscriptions can be a problem for vendors too. The features they offer are built on top of cloud infrastructure that charges them for compute and storage resources. Different features can use more or less of those resources. And if a compute-intensive feature suddenly gets used a lot by certain users — way more than expected — the cost to the SaaS company can turn those users from profitable customers into unprofitable ones.

Insert “we lose money on every feature used, but we make it up in volume” joke here.

There are other issues too, such as increasing usage via automation and integration through other apps. This is a good thing, but it doesn’t always fit cleanly with a seat-based pricing model. More automation and integration can actually reduce the number of human seats needed to work with a particular app.

These challenges with fixed pricing on seats and tiers has led to the rise of a new model: usage-based pricing. Users pay for their consumption of features. If they don’t use a feature, they don’t get billed for it. If they use it a ton, they pay proportionately to cover the cost and margin for the vendor.

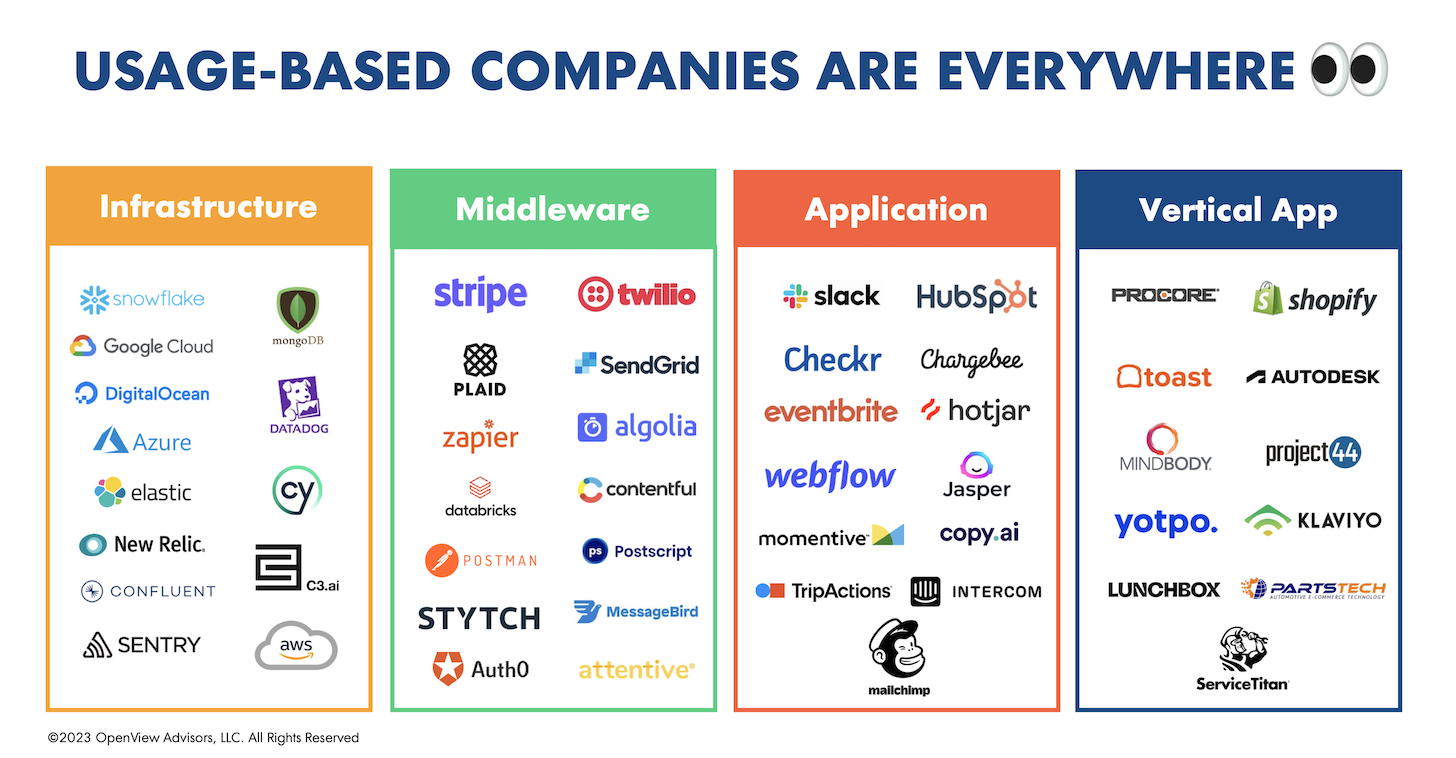

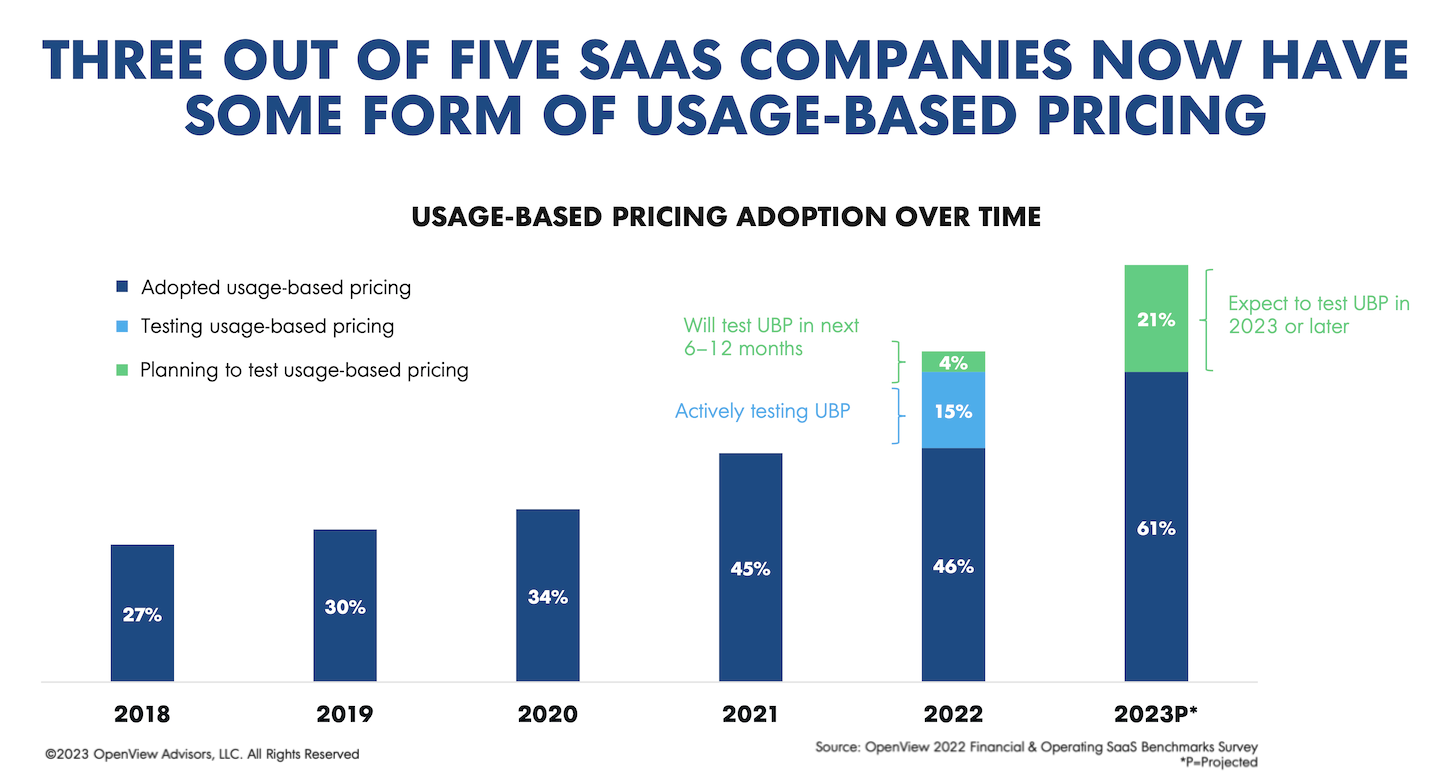

OpenView recently released their 2nd annual State of Usage-Based Pricing report. Perhaps this most striking finding is that the number of SaaS companies using usage-based pricing has more than doubled over the past five years. And it’s expected to grow even more:

Now, some of these products have pure usage-based pricing. Stripe is a great example: you pay per transaction.

Others, have hybrid pricing: you pay for seats and/or tiers, which often include a baseline set of “usage” limits and the ability to exceed those limits by paying for additional usage. HubSpot (where I work) is a great example: a Marketing Hub Pro subscription includes a certain number of marketing contacts (and the ability to email them, which is a real cost), but you can pay to add on as many other contacts as you like.

Most SaaS business applications using usage-based pricing have a hybrid model.

When implemented properly, usage-based pricing is a win-win for customers and vendors. According to OpenView’s research, SaaS companies that have adopted it have 31% faster revenue growth and 9% better net dollar retention.

But the most exciting thing about this trend to me is that it is creating an economic model to support composability in martech apps.

Usage-based pricing is aligned with composability

One of the major S-curve trends ahead in technology that I wrote about earlier this year is “composability.”

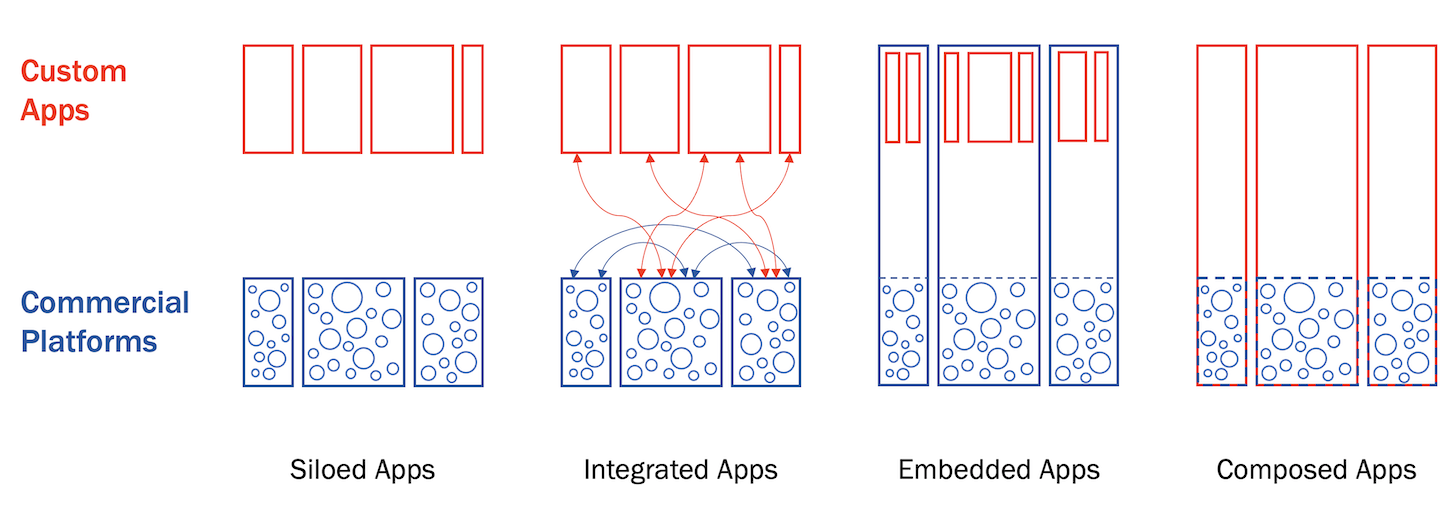

The idea of “composable software” is that smaller software building blocks — API services, functions, data sources, UI elements, etc. — can be assembled together like Lego pieces to craft tailored digital processes, employee experiences, and customer experiences that are unique to your business. They can be easily rearranged as needs shift and opportunities arise.

Composability is exciting because it promises to give us the best of two worlds. We can buy off-the-shelf software capabilities, so we don’t have to reinvent the wheel by building things that are commercially available. At the same time, we can create highly bespoke experiences for our customers and our internal operations by designing higher-level apps and workflows that seamlessly incorporate those commercial components.

In a very real sense, our business becomes a giant custom software app. It is unique — and therefore differentiated in the market. But it’s also efficient in leveraging the comparative advantage of all the software vendors we draw upon in composing it.

But in this best-of-both world, the boundaries of seats and tiers blur and fade. Usage-based pricing, however, works beautifully in this environment.

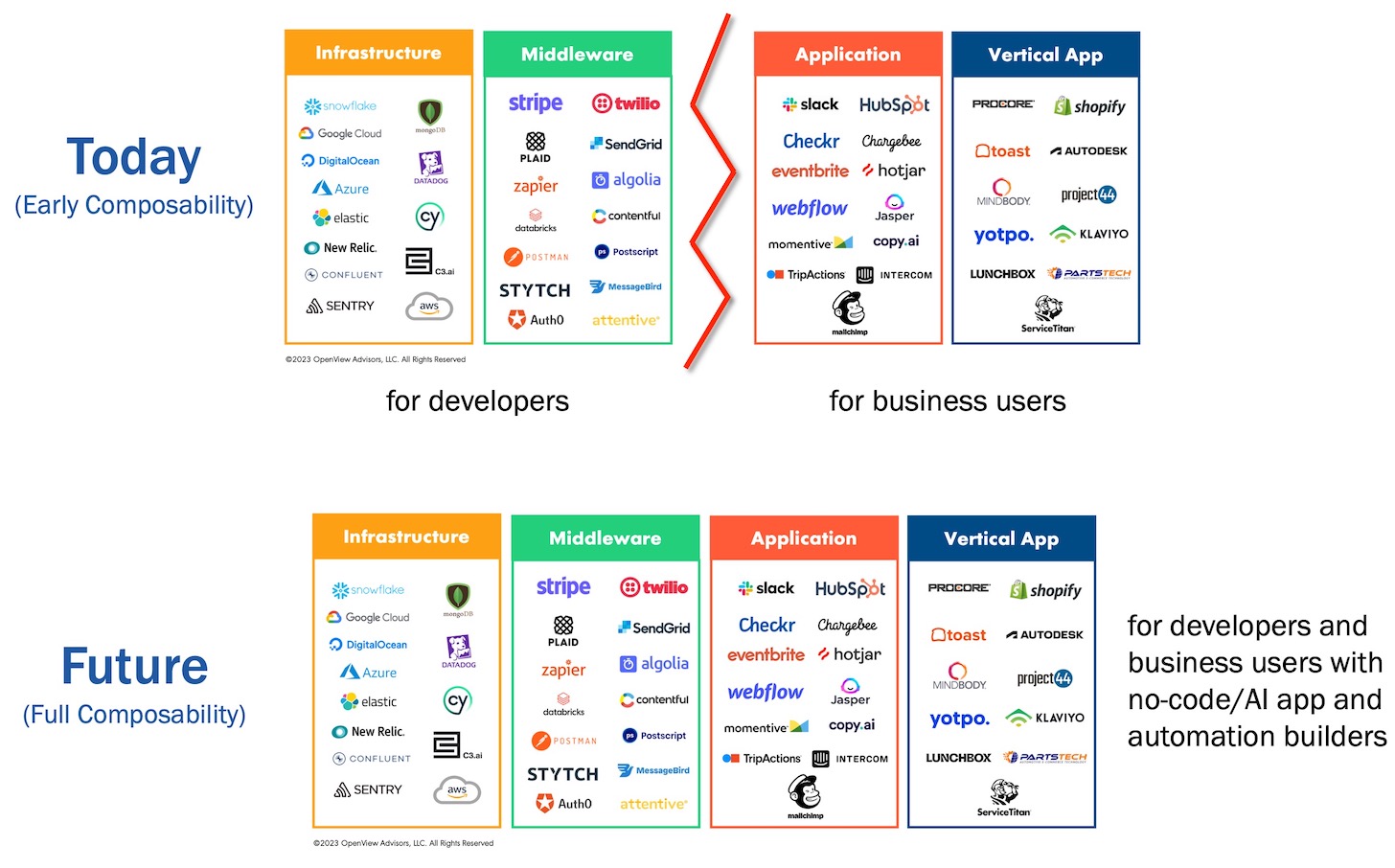

Today, cloud software with usage-based pricing exists in two clusters: those primarily serving developers and those primarily serving business users. There’s blending between the two, for sure. But as the power of AI-powered, no-code tools continues to advance — and as commercially packaged apps initially built for business users open up more and more of their internals via APIs to developers — blending will accelerate. These clusters will converge.

Eventually, everything will be composable. The rise of usage-based pricing is an important step in making that future real.