Tom Wentworth, a pioneering engineer-turned-CMO in the marketing technology space whom I’ve long admired, recently commented on a LinkedIn thread, “Martech is about to face its ‘dot-com’ moment. How many pet stores did we really need in 2000?”

I think he’s right — but possibly not in the way he (or you) might think.

The remark was a reference to the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000, when hundreds of first-generation Internet companies went out of business — including high-profile disasters like Pets.com, (in)famous for their sock-puppet Superbowl commercial before the whole company imploded.

The dot-com bubble was fueled by a wave of venture-backed Internet start-ups, primarily consumer-oriented, that were determined to disrupt and disintermediate on a massive scale. They burned through cash on outrageous go-to-market ploys and lavish employee perks, emboldened by their burgeoning valuations regardless of their lack of profitability.

For most dot-coms, profits never appeared. Actually, in quite a few cases, even barely plausible business models never appeared either.

In 2000, the bubble burst. Within months of the turn of the 21st century, the Internet company landscape was decimated.

So many ventures flamed out in such spectacular fashion that a site called F*cked Company — a parody of Fast Company that had celebrated many of those dot-com businesses at their peak — rose to popularity with its crowd-sourced Schadenfreude documenting the demise of one dot-com after another.

For years afterward, venture capital all but vanished for Internet startups. “Disintermediation” became a punchline. Markets grudgingly accepted a small number of survivors, such as Amazon. But they weren’t in favor. Amazon dropped from $94/share in 2000 to under $7/share in 2001.

By the way, earlier this year, Amazon was at $2,020/share. And that’s not its biggest surprise.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Is martech a dot-com bubble redux?

Tom’s comment was in response to a post about a recent martech acquisition — Terminus acquiring Sigstr. There’s been a stream of martech acquisitions lately. And the author believed that for a number of them, the price paid was “pennies on the dollar.”

I don’t know the terms of the Terminus/Sigstr deal, so I don’t know if that was the case there. (As an aside, I have high regard for both firms.) I have observed plenty of other martech companies sold at fire-sale prices this year. Yet, I’ve also seen quite a few acquired at handsome multiples too. So I’d be wary of jumping to conclusions about this specific one.

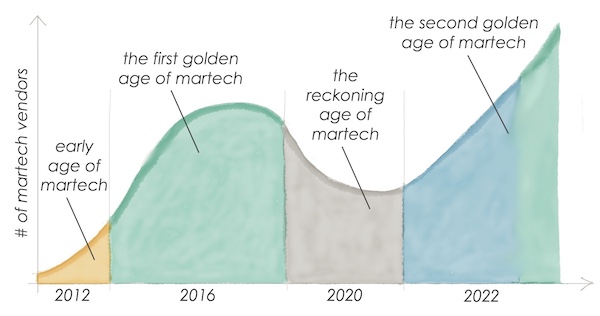

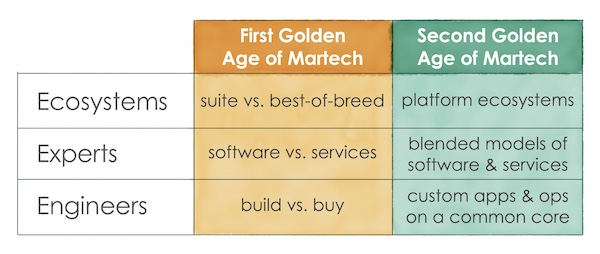

But there’s no denying that we have entered a “Hunger Games” era for many VC-backed martech companies from the first golden age of martech, the period from 2013 to 2018.

Over the past six years, hundreds of martech start-ups raised a ton of capital (Venture Scanner puts the figure at $49 billion) on the promise that they would grow to become widely-adopted, generalist tools that would eventually generate hundreds of millions — or even billions — of dollars in revenue.

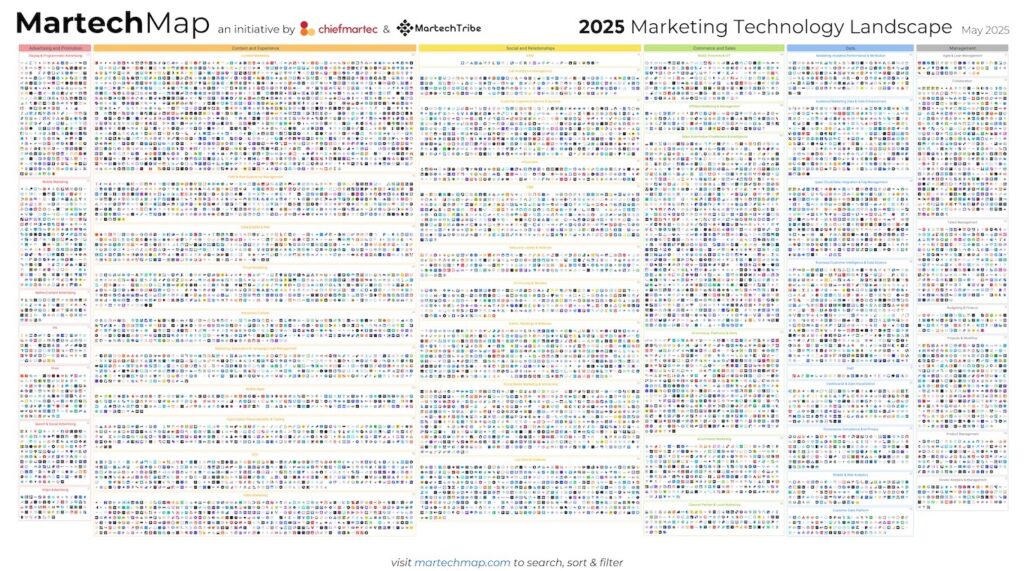

This was one of the forces — although not the only one — that drove the exponential growth of the marketing technology landscape over the past decade.

But math beats marketing, as sure as scissors cut paper. Even with martech sector growing to a robust $121 billion, there are only so many companies that can carve out billion-dollar slices of that pie. They may total in the dozens, but definitely not in the hundreds.

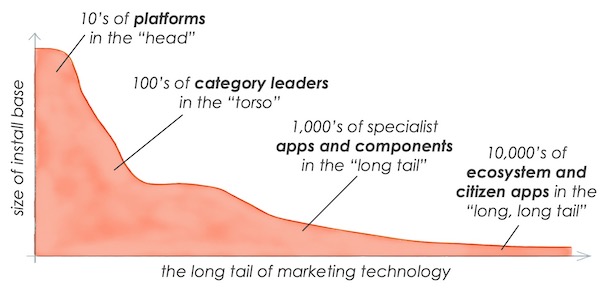

In addition to a ceiling on demand that constrains the total market size, generalist products tend towards winner-take-all or oligarchy dynamics. There’s always potential for one generalist to disrupt another. But most of the time, other firms in a category compete — or engage in coopetition — with a generalist market leader by specializing, serving a particular function, segment, or industry more deeply than the generalist can.

Those specialist businesses can be quite successful — if you define success by profitability and millions, maybe tens of millions, in revenue. But they’re limited by the total addressable market of their specialization, a fraction of the umbrella generalist market. Which means they don’t deliver traditional VCs the kinds of 10X returns that high-risk, high-return investment strategies demand.

The market can sustain thousands of successful martech specialists. But it cannot sustain thousands of billion-dollar generalists. Martech, like most industries, is destined to the power law of a long tail distribution:

The “Hunger Games” dilemma of the current martech sector is that hundreds of VC-funded, aspiring generalists are either losing out to other generalists — they’ve fallen short of their category’s oligarchy of top brands — or are learning that they’re actually low-ceiling specialists. The latter conclusion would be fine, except for the fact that their funding and business models were contingent on being high-ceiling generalists.

Tom wryly noted, “How many pet stores did we really need in 2000?” It’s easy to draw a parallel and say, “How many generalist email marketing tools do we really need in 2020?”

So, yes, martech is facing its dot-com moment.

But what happens next?

What ever happened to that Internet ecommerce revolution?

In 2019, consumers spent nearly $3.5 trillion through ecommerce. That’s trillion with a “t.”

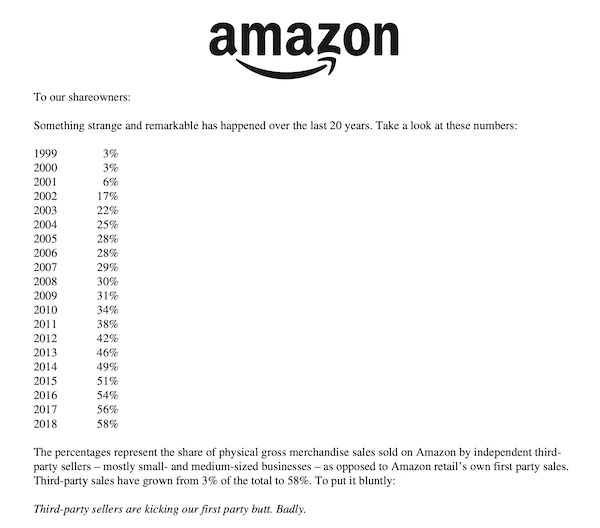

You might be thinking, “Yeah, but most of that was through Amazon.” Total merchandise transactions through Amazon in 2018, their last full fiscal year, was around $277 billion. A significant portion of the market, to be sure, but less than 10% of the $2.9 trillion total in ecommerce in 2018.

So where’s the other 90%? It’s a long tail of hundreds of thousands of ecommerce sites.

What’s really interesting is that out of that $277 billion on Amazon, the majority was sold by independent third-party sellers. Read the beginning of Jeff Bezos’ 2018 letter to shareholders (click to enlarge):

Amazon is actually a platform that supports an enormous ecosystem of thousands small- and medium-sized businesses. It’s not out of altruism. That ecosystem has become a fundamental part of Amazon’s value proposition to its customers. It provides the “best of both worlds” — the standardization of a single ecommerce store with a predictable buying experience and the near-infinite variety of specialized products for every niche a consumer can desire.

Amazon’s biggest competitor arguably isn’t Walmart, with ecommerce sales of $28 billion, but rather Shopify, an ecommerce platform that hosts over a million stores handling $183 billion in online transactions.

By the way, Shopify — which I would classify as part of the marketing technology landscape — thrives in no small part due to their ecosystem of hundreds of apps that plug in to the Shopify platform. This enables merchants to tailor their customer experience and digital operations to their specific business.

Merchants on both Amazon and Shopify are a loooooooooong tail of specialists.

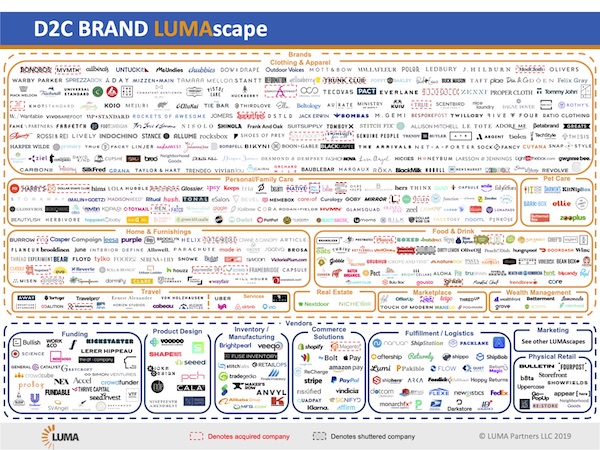

But long tails can have fat torsos. Not every non-Amazon or non-Walmart ecommerce company is small. Some are generating hundreds of millions in revenue. The direct-to-consumer (D2C) industry is red hot — turns out that “distintermediation” had legs after all — and has seen multiple billion-dollar acquisitions (just in razors: Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club). Terence Kawaja even has a LUMAscape of top D2C brands:

So in the second decade after that bursting of the dot-com bubble, the landscape of “dot-coms” — i.e., companies that make most or all of their revenue through digital sales — is many orders of magnitude larger than it was at the peak of 2000.

It’s orders of magnitude larger in both total revenue but also in total number of firms, spread out across a long tail distribution of generalist platforms (Amazon), large category leaders (Chewy.com — take that Pets.com sock puppet!), and hundreds of thousands of small- and medium-sized ecommerce businesses.

If martech follows the same pattern, this “dot-com moment” — as rough as it may be for some — is just the beginning of a bright future for the industry overall. One might even call it The Second Golden Age of Martech.

In fact, I dare to predict that it will follow a very similar pattern.

Why? Because martech is symbiotically bound to the long tail of digital businesses. Specialist businesses succeed because their products — but increasingly also their experiences — are tailored to a unique audience.

While most will likely build their businesses around a small number of generalist martech platforms (again, there’s not much differentiation in basic email delivery mechanics), they will just as likely seek to customize their martech stack with specialist apps and components that shape their front-office customer experiences and back-office processes in innovative and remarkable ways.

This is exactly what happens in the Shopify ecosystem.

By the way, it’s also what we’re seeing in the HubSpot ecosystem too.

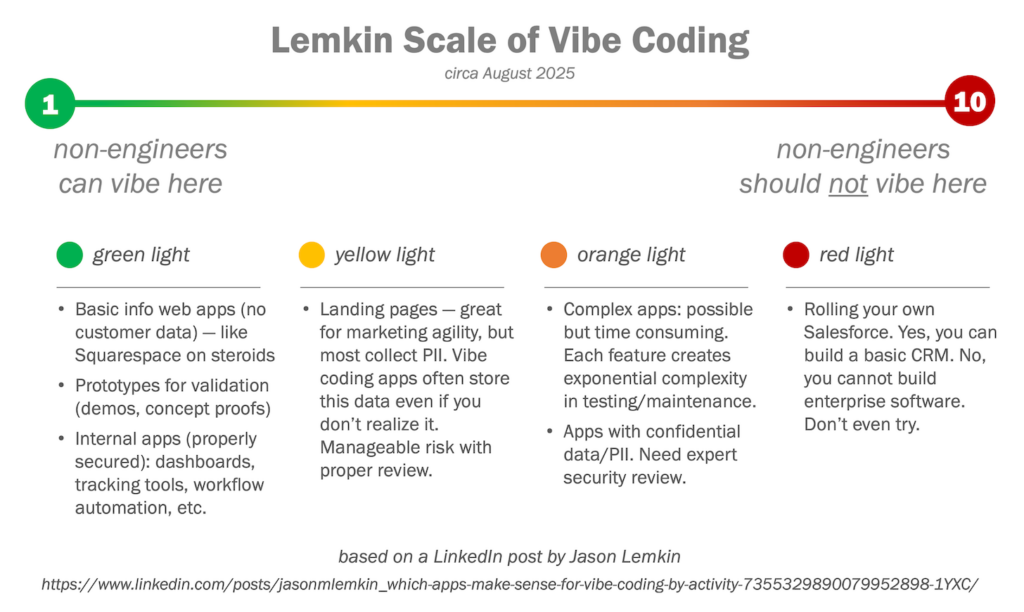

In the far reaches of the long tail, such specialization will ultimately be fed by custom apps built by citizen developers.

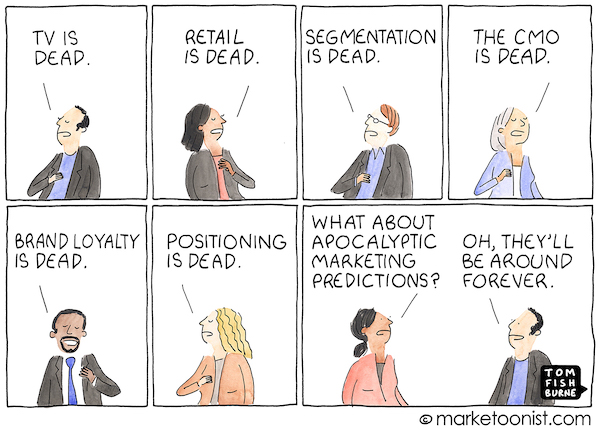

2020 is going to be a messy year of restructuring in the martech industry. But when you start hearing people claim the martech industry is dead, know that it’s likely as dead as that whole consumer Internet thing turned out to be.

As Luke Skywalker said, “No one is ever really gone.”