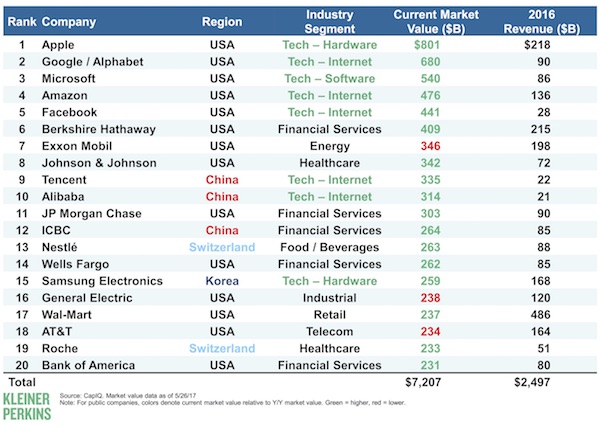

The easy answer, of course, is that they’ll both be controlled by Jeff Bezos and the rapidly evolving Amazon empire. That alone is a pretty remarkable for hybridizing the digital and the physical on such a massive scale.

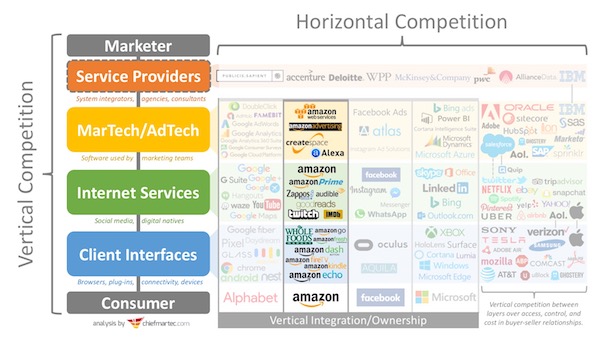

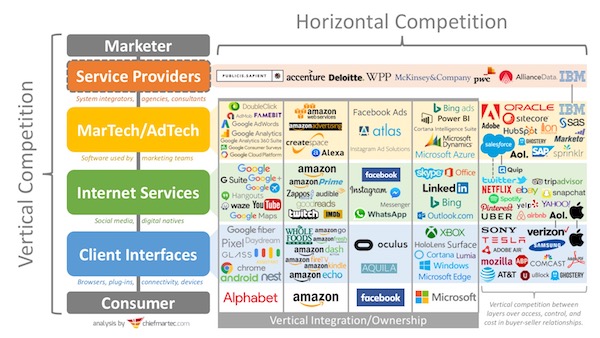

But in my worldview, Amazon’s $13.7 billion purchase of Whole Foods — insert requisite “Whole Paycheck” joke, such as it was cheaper than buying groceries there for the company cookout — gives Amazon a powerful new touchpoint in their vertical competition pipeline between marketers and consumers. (For an explanation of such pipelines, see 5 Disruptions to Marketing, Part 3: Vertical Competition.)

Through that lens, what do Amazon Alexa and Whole Foods have in common?

They’re both client interfaces.

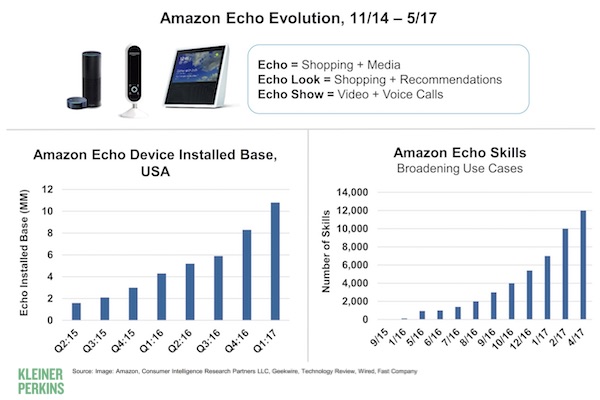

It’s through client interfaces that we humans in the real world connect with digital services in cyberspace. The classic client interface of the Digital Age has been the web browser. Then smartphones. And more recently, an explosion of new interfaces — from chatbots to VR — including voice-controlled interfaces such as Alexa, through her Echo family of devices.

I’d contend that Whole Foods is a “client interface” too.

It’s way more immersive than virtual reality. It’s actual reality. People walk into physical stores, where they see and touch real things and interact with real staff. In real-time. (Sorry.)

So I’ve updated my vertical competition map for the martech industry, shown at the top of this post with Amazon’s vertical pipeline highlighted, to reflect this.

Alexa and Whole Foods are actually “walled gardens”

From a strategic perspective, the most fascinating trend with client interfaces — that “last mile” to the consumer — is the shift towards proprietary or exclusive platforms.

Web browsers were completely open and largely commoditized. Any web browser could connect to any website. As a marketer trying to reach your audience in the digital world, you didn’t need to care whether they were using Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Explorer, etc. (Granted, browser compatibility issues have been a royal pain because browsers aren’t perfectly identical commodities. In the big picture, however, these were relatively minor issues that didn’t effect strategy.)

But the pitched battle in vertical competition today is who controls exclusive client interfaces.

Amazon Alexa is a perfect example of such an exclusive client interface. If a family has an Amazon Echo in their house that they use for most voice-controlled discovery and commerce, Amazon essentially has them in a “walled garden.” If marketers want to reach those consumers through Alexa, they have to do so on Amazon’s terms.

There are now thousands of Alexa skills. And while it’s great that marketers can build them to piggyback on Amazon’s Alexa client interface — memo to classic martech platform companies: this is what a thriving third-party ecosystem looks like — Amazon ultimately gets to decide who can participate and what they can do.

Just as Apple killed a hundred iOS “flashlight” apps overnight when they decided to add that feature natively into the iPhone, Amazon can cherry-pick the interactions that it wants to own — and it can grab new ones anytime, without any warning.

Whole Foods is the physical store equivalent of such a “walled garden.” Amazon will be able to exclusively decide whose products are available through their channel and under what terms. People who shop at Whole Foods will only be presented with what Amazon chooses to present to them.

Remember the influence that Walmart has wielded over suppliers? This will be similar. It’s not just about pricing pressure (although that will certainly be a factor). They may bend suppliers to their will in how packaging and in-store marketing operate, particularly in the context of new physical-digital interfaces — shaping whole new kinds of shopper experiences that will further strengthen the walls of their walled garden.

There’s one more point I’d like to make.

Disruptions such as this — Amazon absorbing Whole Foods and transforming into a new kind of digital-physical walled garden — are a perfect example of why it’s hard to predict the future of martech.

Linear extrapolation of the software strategies of the past four decades doesn’t get you to these conclusions. It’s a non-linear jump.

While SAP (Hybris) and Salesforce (Demandware) are competing with each other horizontally on who can have the best classic enterprise e-commerce software platform, Amazon — with Alexa and Whole Foods — is redefining the vertical playing field on which e-commerce exists.

If SAP and Salesforce aren’t deeply concerned about that, they’re not paying attention.

To put this into the context of the consumer, imagine your shopping experience in Whole Foods being just as efficient as shopping online, while still being able to touch, taste, drive by, pick up deliver, in the physical world. Upgrading the physical experience is the opportunity, and if Amazon succeeds at that, we as consumers will vote with our wallets in droves. Generally the retail experience has been dreadful, so I hope Amazon succeeds here, and paves the way for a dramatic improvement in offline retail experiences across the whole retail category. The shopping mall my kids will frequent in their teenage years a decade from now, will be much richer and completely different than the shopping malls of today. Bring it on. From a MarTech perspective, cross channel nurturing is “kinda” easy when those channels are all digital, but the challenge and opportunity for MarTech is to also orchestrate nurturing across offline channels too, and whole foods might just be the poster child of that challenge and opportunity.

Well said, sir.

Scott,

A wonderful post, I had not considered it in this context.

As a further piece of the evidentiary puzzle, look at what Bezos has done in his personal domain of the Washington Post, turning it back to profitability with quality journalism, based on in house software that makes the consumer of news (and ads) the focal point.

A living example of your ‘walled garden’ at work.