At the MarTech conference last week, Mayur Gupta, global VP of marketing & growth at Spotify, and I revealed the results from a study we had conducted with the research team at Third Door Media on the intersection of art and science in marketing.

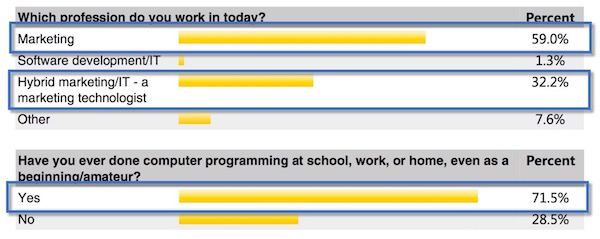

We had 637 participants in the study — one of the largest groups surveyed on this topic in recent history — the vast majority of whom identified as marketers and marketing technologists:

Looking at the distribution of participants, it was quite heartening to see how many identified themselves as marketing technologists, hybrid marketing/IT professionals. It’s worth taking a moment to appreciate how much that discipline has coalesced and grown over just a few short years.

We also found it fascinating that 71.5% of all participants had done computer programming — even if just in school or as an amateur — at some point in their lives. While not every marketer needs to be a programmer, this data suggests a growing maturity of “digital fluency” in the profession. Familiarity with software dynamics and algorithmic thinking have become valuable parts of a marketer’s mental model in today’s environment. You don’t have to be a code jockey to benefit from this understanding.

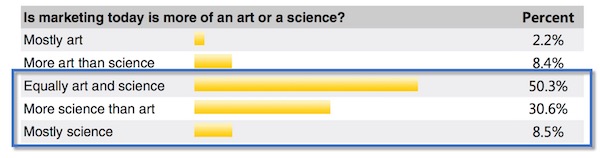

The obvious first question was: Is marketing today more of an art or a science? And, not surprising, the results skewed towards the “science” end of the spectrum.

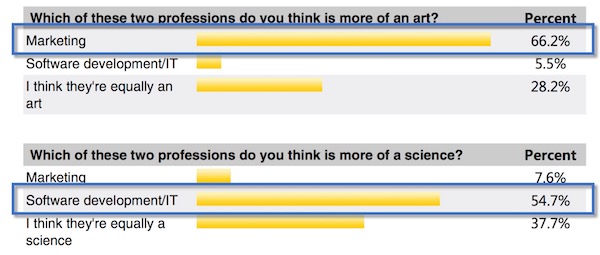

But we wanted to see how they would compare marketing on the art/science continuum relative to another profession: software development. (An intriguing choice, given how the worlds of software and marketing are increasingly entangled.)

In that context, 66.2% believed marketing was more of an art, while 54.7% believed software development/IT was more of a science. So, the net sentiment would seem to be: “marketing is becoming more of a science, but not nearly as much as the discipline of software.”

While it is interesting to see this hedging around how science-y marketing really is, I also suspect this reveals ongoing misconceptions about the nature of software development. Although computer programs are quintessential analytic engines — often to a fault — the process of creating computer programs involves a tremendous amount of art and creativity. (For better and worse.)

So what do people even mean when they think of art and science in marketing?

We asked participants to share three words that they associated with the art of marketing and three with the science of marketing. As shown in the word cloud above, the “art of marketing” evoked thoughts of:

- creative

- design

- content

- brand

- emotion

- strategy

The “science of marketing” clustered a little more tightly around:

- data

- analytics

- analysis

- testing

- technology

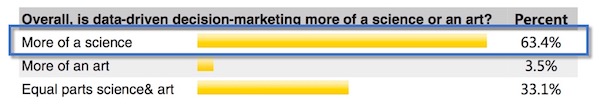

Essentially, the science of marketing seems to primarily revolve around data-driven decision-making and experimentation. Anticipating this, we asked the question: Overall, is data-driven decision-making more of a science or an art?

Not surprisingly, 63.4% think data-driven decision-making is more of a science. That’s the popular (mis)interpretation of “data-driven” — that it’s relatively formulaic, like a physics equation or a chemical reaction, precisely defined and predictably repeatable. (Time to trot out my yearly shout back to 14 rules for data-driven, not data-deluded, marketing.)

It was encouraging, however, to see that 1/3 of the respondents recognized that it is an equal blend of both art and science.

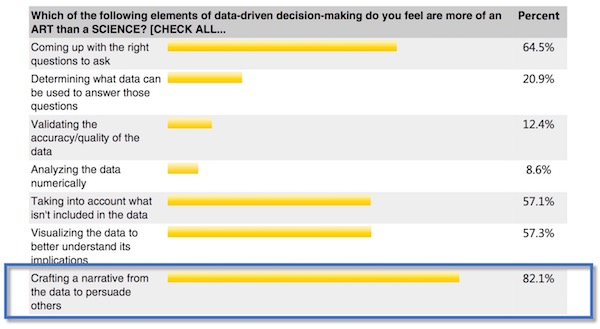

So we followed up by asking, Which of the following elements of data-driven decision making do you feel are more of an art than a science?

The top two ranked in that list really pop out:

- 82.1% — Crafting a narrative from the data to persuade others

- 64.5% — Coming up with the right questions to ask

And the next highest ranked ones are arguably variations of those two as well:

- 57.3% — Visualizing the data to better understand its implications

- 57.1% — Taking into account what isn’t included in the data

There’s an art to asking the right questions, and an art to telling the stories from the results. There’s no algorithmic recipe that automatically solves those challenges. (At least, not yet — exponential growth in AI will increasingly deliver some amazing/scary overlaps with those “human” talents we cherish today. But we’re not there yet.)

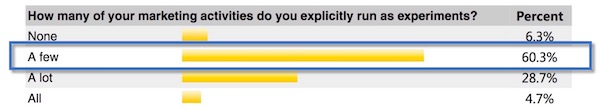

The other marketing-as-science theme is testing and experimentation. Scientists run experiments. Marketers run experiments. Therefore, marketing = science. Right? (That’s a pop quiz on transitive logic fallacies for you budding data scientists.)

But seriously, most marketers have clearly embraced experimentation as an integral part of their work, with an overwhelming 93.7% reporting that they explicitly run experiments on at least a few of their marketing activities:

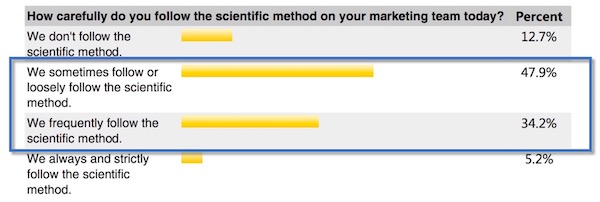

But the majority — 60.6% — admit that they either don’t follow the scientific method or only follow it sometimes or loosely. Kudos to the other 39.4% who always/strictly follow it, or at least do so frequently:

If you don’t follow the scientific method — observations, questions, hypotheses, testable predictions, and the acquisition of relevant data to support or refute those hypotheses — then it seems like “experimentation” is simply a fancy word for “throwing a bunch of things against the wall and hoping one of them sticks.”

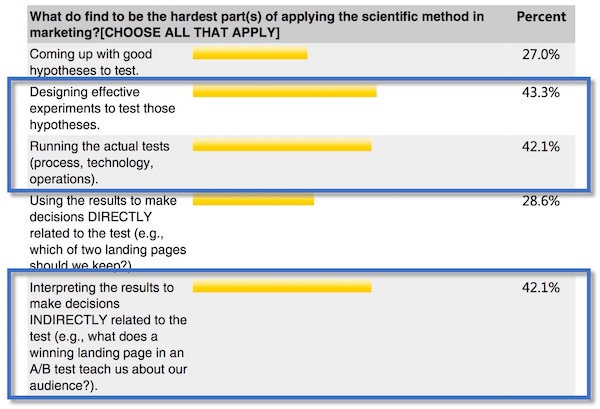

The truth is that being scientific in one’s experiments — i.e., following the scientific method — is hard:

In particular, designing effective experiments to test your hypotheses is hard to do. 43.3% of the participants in this study said it was the hardest part of applying the scientific method in marketing.

If marketing is becoming more scientific, it is — at best — a soft science, connected with fields such as psychology, sociology, economics, and anthropology. Any professional researcher in those disciplines will affirm how difficult it is to design effective experiments that will clearly support or refute a hypothesis. And running those tests isn’t easy either.

The truth is that there’s an art to designing and running great experiments, even as — or because — the underlying process demands scientific rigor. Great science is incredibly creative.

This is where experimentation and data-driven decision-making intersect. The data from most marketing experiments inevitably comes with a number of important caveats. It was almost certainly not collected under controlled, labratory conditions.

Factoring in the other variables, known and unknown, that could have affected the outcome can make it a little hard to use the results to make decisions directly related to your test — as 28.6% reported — such as “Which of two landing pages should we keep?” But it’s really hard to interpret those results to make decisions indirectly related to the test (e.g., “What does a winning landing page in an A/B test teach us about our audience?”). 42.1% identified that as one of the hardest parts of applying the scientific method in marketing.

The takeaway for me from this study is that marketing is steadily adopting more scientific thinking in our discipline, which is a good thing. Data-driven decision-making and experimentation are powerful tools for the digital age. But the art of how we apply those tools is incredibly important to our success.

As Mayur said on stage during our presentation — and forgive me if I’m slightly paraphrasing — “The future of marketing is having more science in our art and more art in our science.”

Well said.

P.S. For a related read, check out this article from 4 years ago: pragmatic marketing vs. hype cycles and false dichotomies. Don’t let art and science in marketing be a false dichotomy.

What a terrific piece of research.

Looking at the recent marketing graduates (recent is relative, I graduated in 1972 before anyone had heard the term ‘marketing’) there is a huge dichotomy.

On one hand, there are some very smart youngsters who are attracted and excited by both the creative and analytical challenges, and there are those who failed to get into the advanced basket weaving course at Uni, so there was just marketing left.

While these differences will be sorted out pretty quickly by the market, they all end up with a degree in marketing, and my concern is that the professionalism of the good ones is being denigrated by the number of dills who can and do call themselves ‘marketers’ with a degree to prove it.

It is a bit like paying to buy an expensive camera, then calling yourself a photographer.