This is part 3 of a five-part series, providing an update on the 5 Disruptions to Marketing as we head into 2018. If you have not yet read Part 1: Digital Transformation (2018 Update) or Part 2: Microservices & APIs (2018 Update), you might want to start there.

3. VERTICAL COMPETITION (2018 Update)

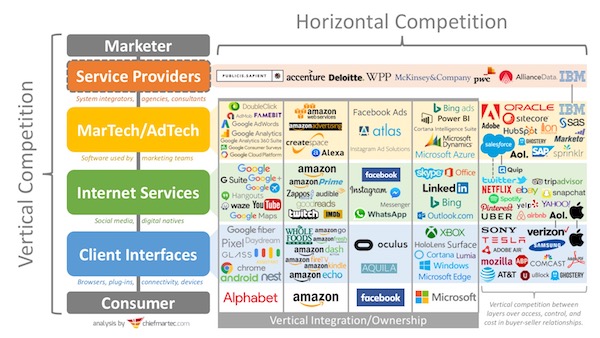

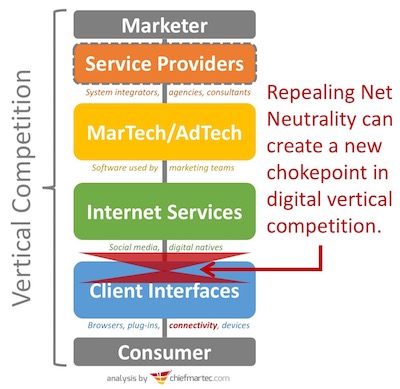

I have been writing about vertical competition in digital marketing for several years: how companies at different points along the pathway between the marketer and the customer exert power and extract value.

The most powerful “competitor” in vertical competition is one who has an exclusive gateway to the customer. If you want to reach customers through their channel or touchpoint, you must agree to their terms — or forgo access.

I think it’s one of the most disruptive force in business today, in part because companies are less likely to see it coming. It’s easy to see Oracle and Salesforce as competitors in martech (they’re horizontal competitors vying with each other at the same stage of the channel). It’s less easy to see Facebook, Amazon, or Verizon as “martech” competitors to Oracle and Salesforce — but in the big picture of vertical competition, they are.

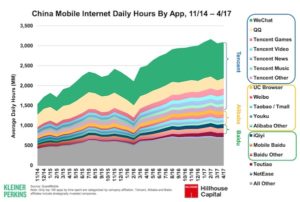

For a large scale example of vertical competition dynamics in digital channels, look at the incredible power wielded in the Chinese Internet market by Tencent, Alibaba, and Baidu. They control the interface — and data — of the vast majority of consumers in that market. Marketers who want to reach those buyers digitally, must do it through their marketing solutions, such as Alibaba’s Uni Marketing suite or One Tencent’s integrated marketing services.

However, here in the US, we’re seeing vertical competition on the Internet grow too.

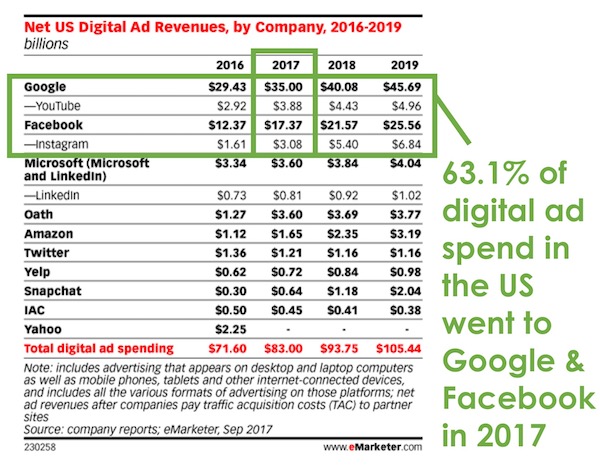

The most common example is the duopoly of Google and Facebook in digital advertising. 63.1% of all advertising dollars in the US went to those two companies — and their portfolio of sites, such as YouTube and Instagram.

They wield enormous power because there are few substitutes for reaching their audiences. If you’re unhappy with Google’s search advertising prices and policies, what are you going to do? Move your search spend to Bing? (Sorry, Microsoft — I love you.)

Same with Facebook and Instagram. Snap and Pinterest might be competitors, but they’re not really substitutes.

This is why, despite vocal resistance from major advertisers such as Proctor & Gamble over measurement and visibility issues, Google and Facebook have each been able to hold on to their dominance. Third-party adtech vendors aren’t able to be of much help, as they don’t have a lot of weight against Facebook or Google to force their way into those walled gardens.

And the strength of Facebook and Google reach beyond their walled gardens. They’ve been highly successful at having independent websites install their “tracking” scripts — whether it’s for Google Analytics or Facebook Connect.

The latest Tracking the Trackers study conducted by Ghostery found that Google had its scripts on almost half of the pages they found on the web; Facebook has its on more than a fifth.

But the Facebook-Google digital ad duopoly is only one example of vertical competition.

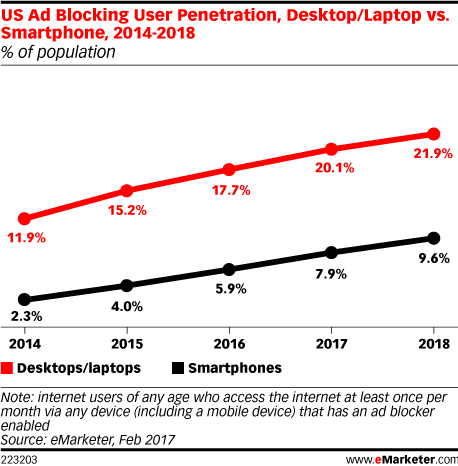

In the battle for digital advertising, ad blockers are another kind of vertical competitor that have continued to grow in 2017.

When a user has installed an ad blocker on their computer or mobile device — that “last mile” between the marketer and the consumer — much of the power of adtech vendors (and even Internet service juggernauts such as Google and Facebook) can be diminished by these client-side players.

In fact, it’s at the client stage — the touchpoint used by the consumer and how it is connected to the Internet — that the biggest struggles in vertical competition are emerging.

Web browsers were relatively weak vertical competitors because they were effectively commoditized. But now, we have an explosion of new proprietary devices and apps that have more power as exclusive touchpoints to select audiences.

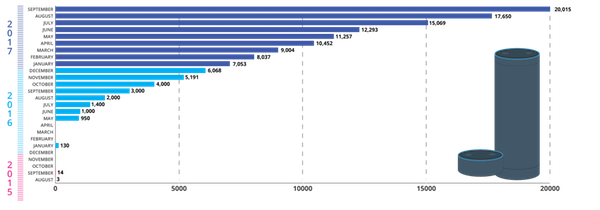

Amazon Alexa is a great example of a proprietary client. It’s estimated that there are over 20 million Alexa devices out in the world. In people’s homes, they essentially “own” the ambient voice command interface. Their nearest competitor is Google Home, with approximately 7 million devices sold.

If you want to engage with Alexa owners through their smart speakers in their living rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, etc., you have to do so by Amazon’s rules. As a result, there have been over 20,000 custom skills created for Alexa, many by brands looking to reach their audience through that proprietary touchpoint:

This creates powerful network effects for Amazon — more consumers buy Alexa devices because they offer more skills, and in turn, that larger audience incentives more brands to build skills for Alexa, and so on into a virtuous cycle.

Earlier this year, when Amazon acquired Whole Foods, you could argue (or, well, actually I argued) that this network of physical stores becomes another proprietary touchpoint between brands and marketers.

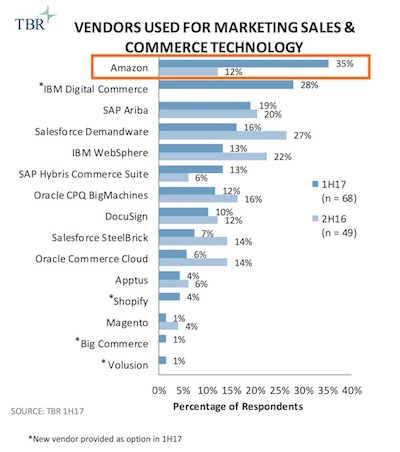

What makes Amazon such a formidable vertical competitor in the martech space, however, is that they have much more than these exclusive client interfaces.

They also have the largest ecommerce platform and a growing advertising platform that is starting to rival Facebook and Google.

Their greatest strength as a martech/adtech player is their unique channels and touchpoints and the exclusive data they have on all the buyers on Amazon.com.

Now, while popular and proprietary client interfaces can have a lot of power in a vertical competition chain, they don’t necessarily have all the power. The power accrues to the vendors that are marketers or consumers — the two end-points of that chain — are reluctant to, unwilling to, or simply unable to substitute.

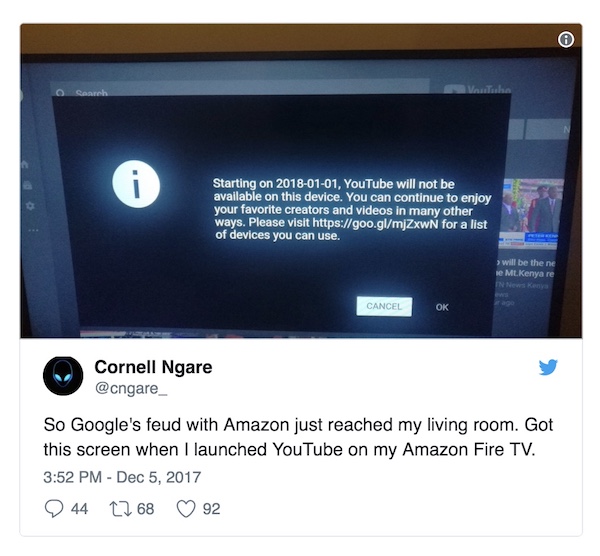

For an example of this, consider the feud between two of these giants, where YouTube is blocking Amazon Fire TV and Echo Show devices. Amazon refuses to sell certain Google products in their store — Nest Secure, Chromecast, Google Cast — so Google now prevents a number of Amazon devices from being able to access YouTube. (hat tip to David Raab for alerting me to this story)

This is hardball vertical competition between an Internet service (YouTube) and a client device (Echo Show): will consumers stop using YouTube or move to a different device other than the Echo Show? It depends on which they value more.

And, by extension, which one will brands value more.

Google is setting a disappointing precedent by selectively blocking customer access to an open website. – Amazon spokesperson

But it’s not just the giants that are playing with vertical competition. Earlier this month, Zeta Global — a growing marketing cloud provider that competes with the likes of Adobe and Oracle — acquired the popular blog commenting service Disqus.

Just as Facebook Comments lets Facebook “own” an exclusive touchpoint on any blog that adopts it for their commenting system — nice for the blogger to have comments only from identified Facebook users, but also very nice for Facebook to have access to all the data of those interactions — Disqus gives Zeta proprietary reach to consumers and their data beyond its back-office martech software.

But arguably the biggest news in vertical competition at the end of 2017, at least here in the US, was the FCC repealing net neutrality.

All of a sudden, this gives the connectivity providers on the client side — AT&T, Comcast, Verizon, etc. — tremendous power in pretty much every vertical competition chain on the Internet.

They used to have relative little power, essentially as commoditized as web browsers. But now, they can block — or effectively block by throttling bandwidth — any site or service on the Internet.

They now control a chokepoint between marketers and consumers in the digital world.

How exactly this will play out remains to be seen — and indeed, legal battles and legislative countermeasures may yet intervene. But there are well-founded concerns that this will impact not only digital advertising and adtech, but also freemium and content marketing models, and potentially every digital marketing tool that has a direct touchpoint with the consumer.

It’s also a testament to how disruptive governments can be in vertical competition.

We see this the Great Firewall of China, the European Union’s GDPR (where data is not just an asset but a liability), and now the repeal of Net Neutrality here in the US. Depending on where your service is located — or where your audience is located — you can be subject to different rules and, as a result, different vertical competition dynamics.

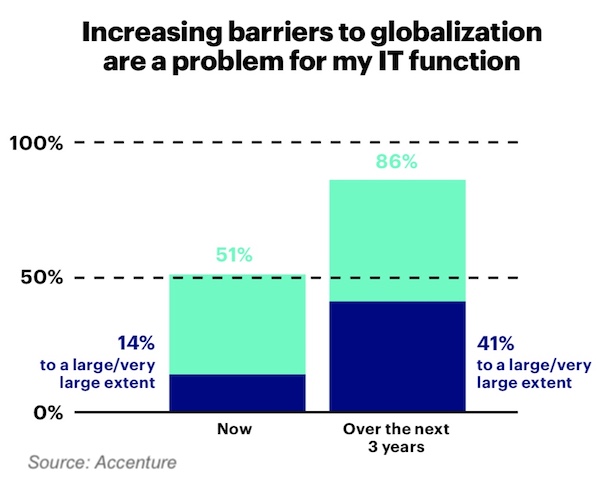

A new Accenture report on digital fragmentation warns that the growth of national digital barriers is making the digital environment increasingly complex and risky for businesses.

Between the power of the Internet giants, an explosion of proprietary touchpoints, and the rather disjointed and unpredictable rules of digital engagement being enacted by different governments around the world, “digital strategy” is going to be harder ahead.

But where there’s a threat, there’s also an opportunity. Stay tuned for Part 4: Digital Everything (2018 Update), where we’ll consider the upside of all these blossoming new varieties of client interfaces.

Very insightful analysis, as always. I’m curious where you see the content creators / providers in this mix? Many of the big players are investing heavily in content and of course the biggest players like Comcast already own major studios. Are we past the “content is king” era? I don’t think so necessarily, but the marketing strategy tied to content is becoming ever more complicated. Have always hated the fact, for example, that DirecTV had the exclusive for NFL. It’s an interesting dynamic to see the NFL try to spread across channels and devices for the consumer, but at the same time being limited by ever-evolving advertising, technology, and distribution mechanics.