Last month, I published the latest marketing technology landscape. It grew yet again, defying many a pundit’s prior prediction, swelling to 8,000 martech solutions.

Upon its release, two things immediately happened:

- A bunch of people insisted it would consolidate dramatically.

- A bunch of companies emailed me to complain they weren’t included.

The irony of those two competing narratives flooding my inbox at the same time — which I’ve witnessed every year for the past decade in nearly parodied Groundhog Day fashion — never ceases to leave me shaking my head in wonder.

While the arguments for consolidation make sense on a lot of levels, the empirical evidence to the contrary — at least with regard to the total number of apps in the market — is undeniable. Something else is happening.

But what exactly is that something else?

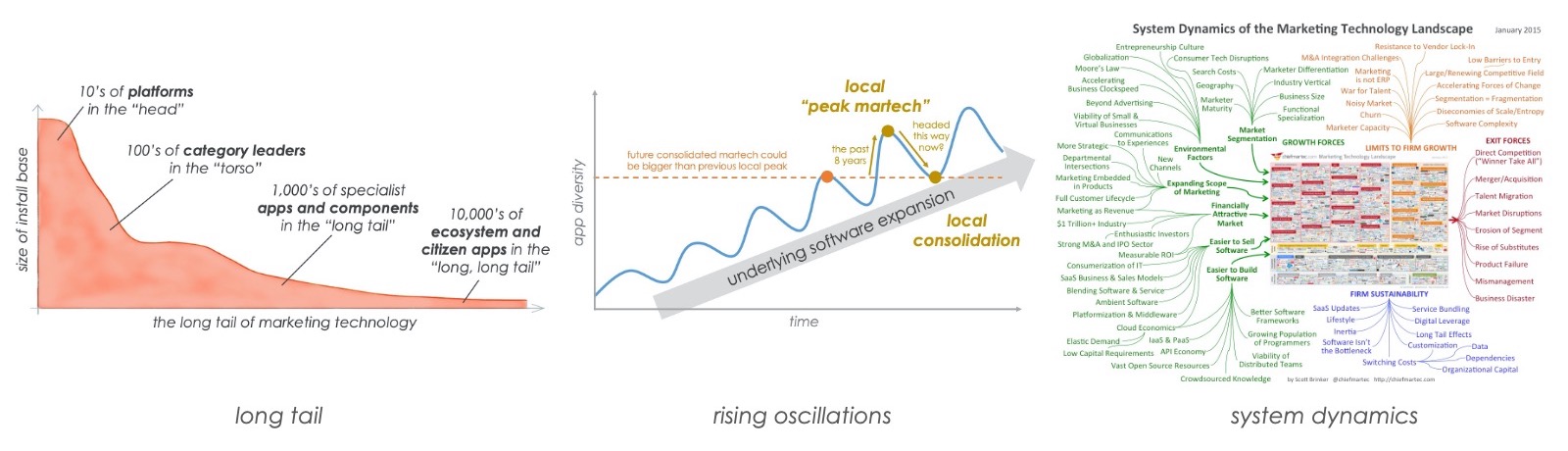

I’ve drawn it as a long tail. I’ve illustrated it as an oscillating wave of expansion and contraction soaring upward on the back of a much larger wave of continuous software growth. One year, I even mapped out a giant system dynamics causal loop diagram to show all the forces pulling and pushing on each other in this market.

Each of those visualizations provided a lens on the martech industry. But I think I have a better one to explain both the “what” and the “why” of the simultaneous expansion and consolidation in marketing technology — a paradox we’ve wrestled with for the past decade, and one that I anticipate will continue in the decade ahead.

The Relationships Between Platforms and Apps Explain Everything

Structure determines behavior. Or perhaps the other way around. Certainly the structure of the modern software industry helps explain the behavior we see in martech and other SaaS markets.

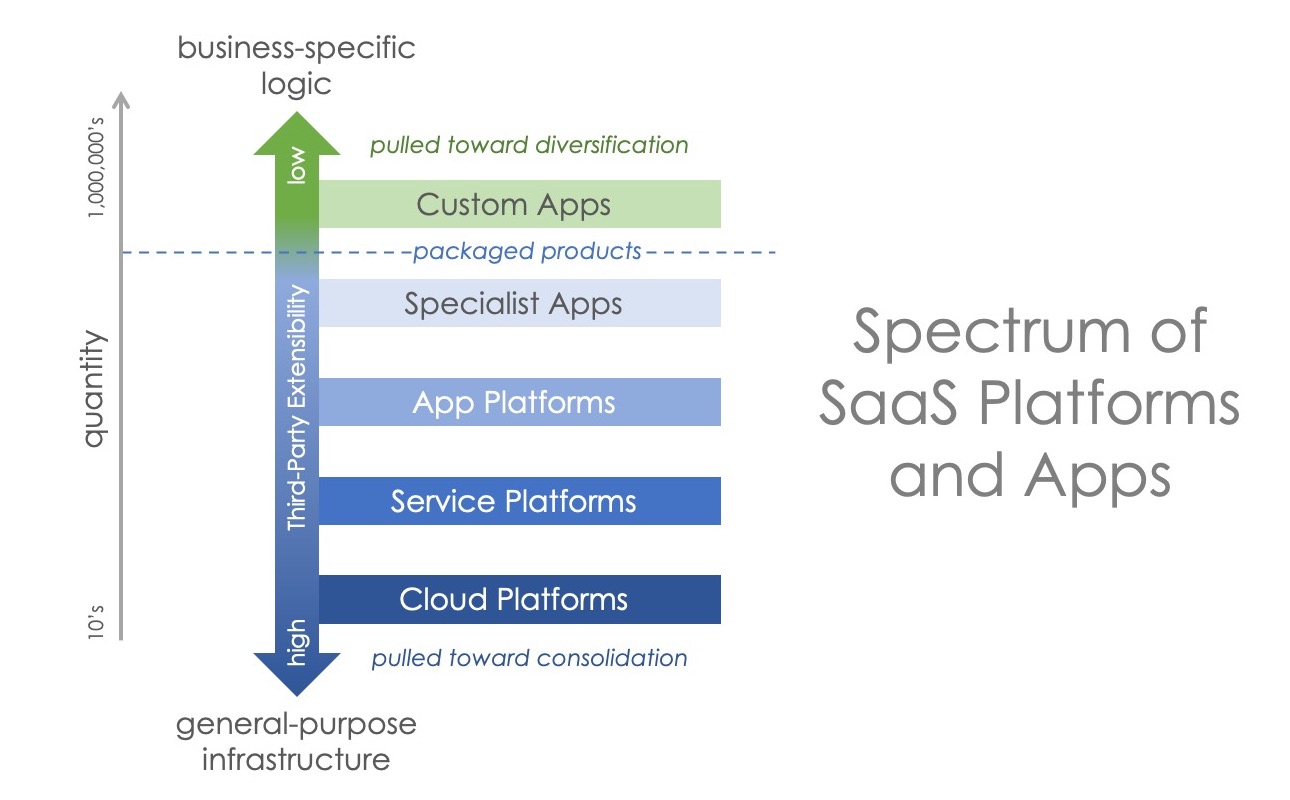

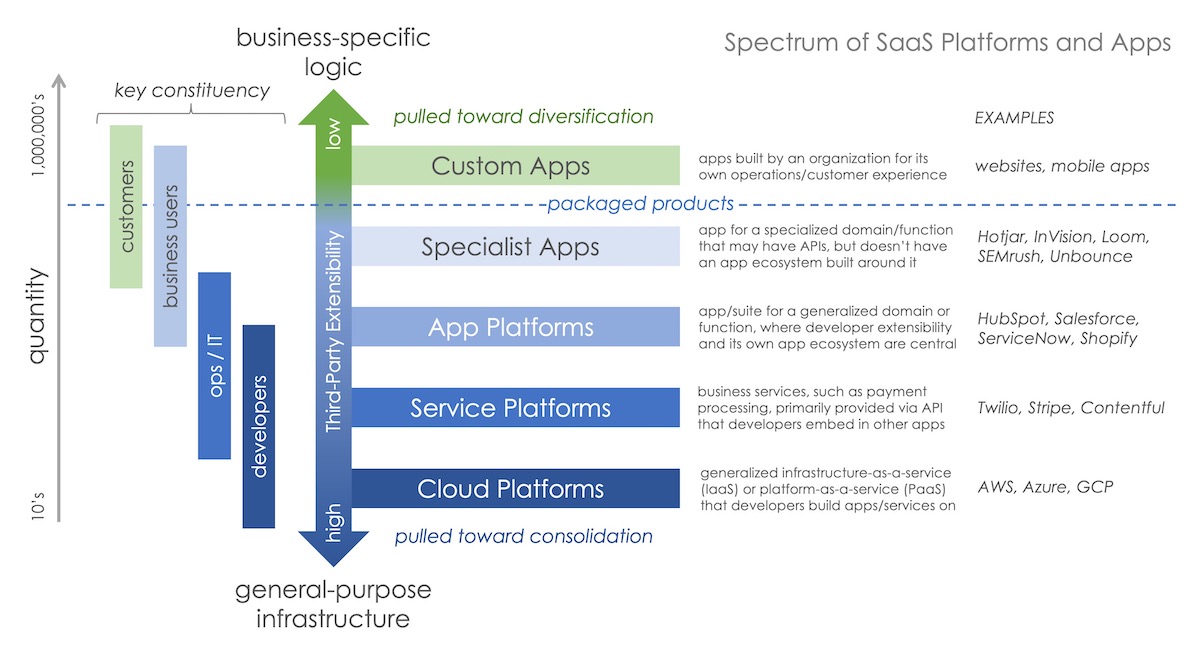

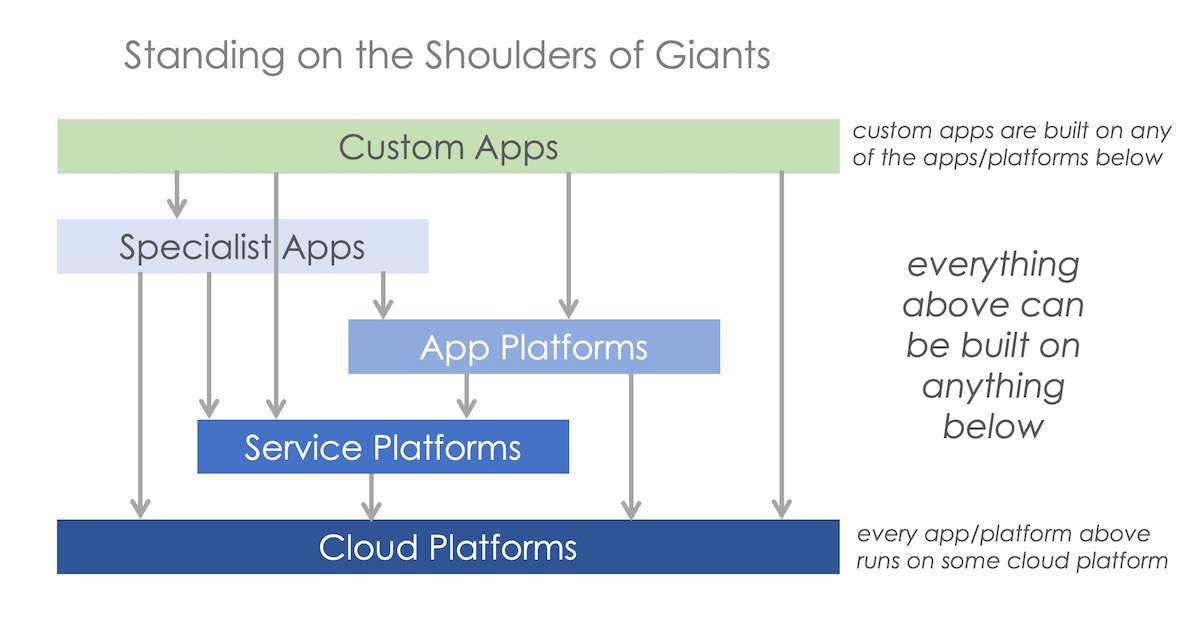

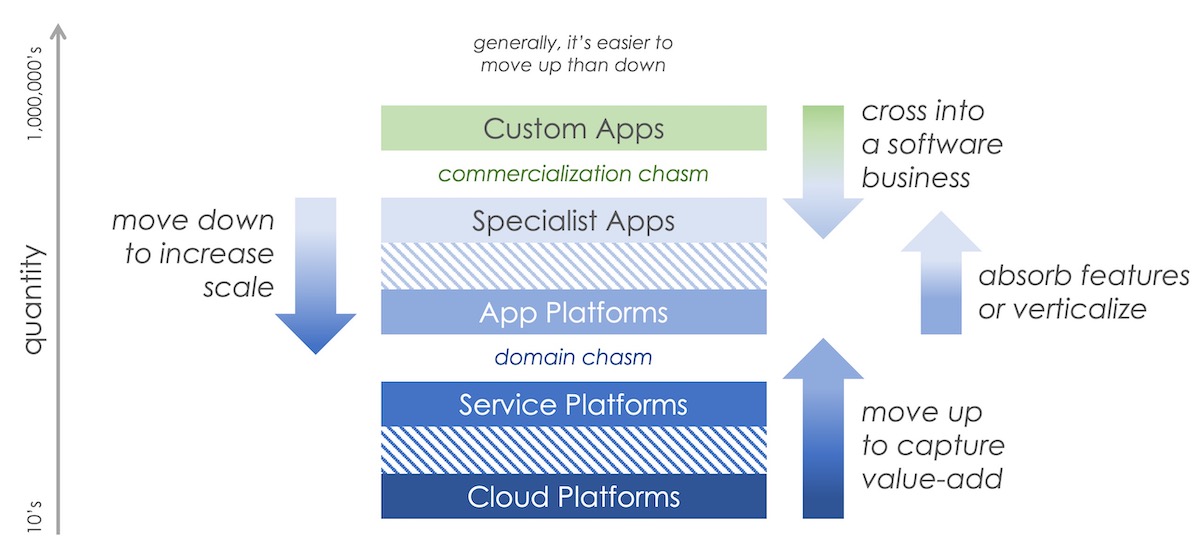

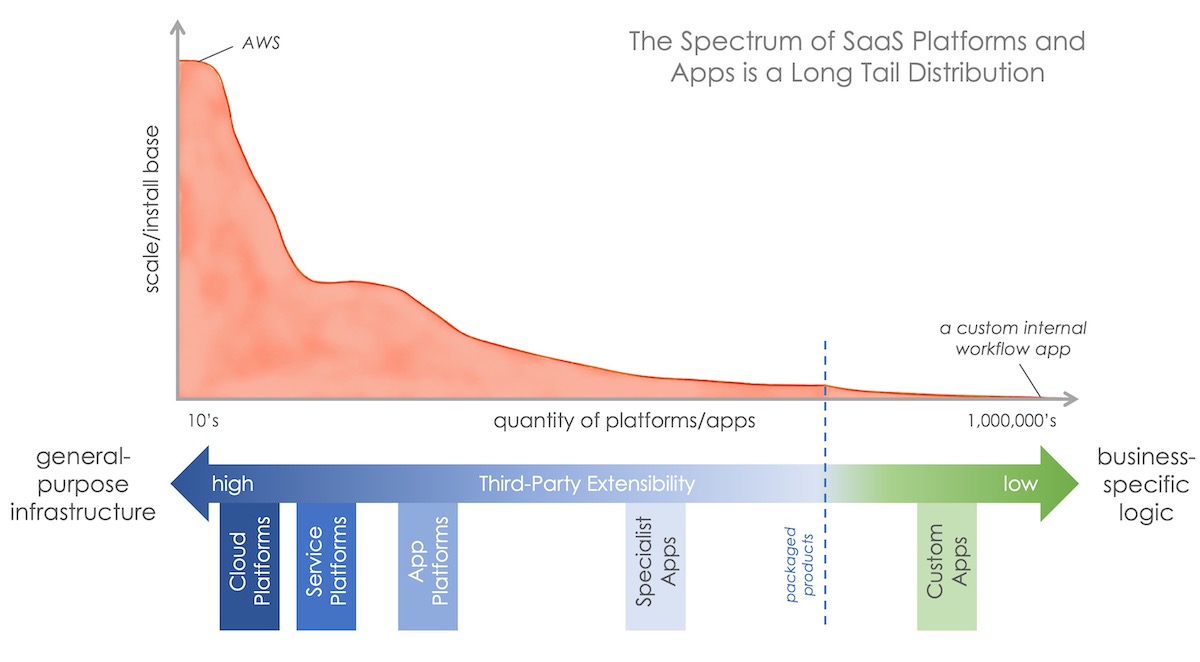

The above chart illustrates the spectrum of cloud-based platforms and apps, from the bottom up. Three attributes are remarkably aligned across this spectrum, and not coincidentally:

- Specificity: from general-purpose infrastructure to individual business-specific logic.

- Extensibility: from open platforms that power every business in the cloud to custom apps that other apps don’t typically build complementary businesses around.

- Quantity: from highly consolidated cloud platforms with only a few dozen players to millions and millions of custom apps.

This is how the modern software industry is structured. Pretty much everything is “in the cloud” — software-as-a-service (SaaS) — even if bits and pieces also run on “the edge” on our laptops, mobile phones, or connected appliances.

Cloud platforms, such as AWS, Azure, Google Cloud Platform, etc., are the foundational layer underpinning all software in the cloud. They started as infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) — providing raw, if virtualized, computing machinery on demand. They evolved into platform-as-a-service (PaaS), insulating developers entirely from the antiquated concepts of hardware. Today, you write software on these cloud platforms, and it just runs, without any care about the mechanics hidden below. AWS Lambda — “serverless compute” — is the quintessential example of this.

There are two important things about these cloud platforms:

- They’re extremely extensible. Their entire business model is to empower developers to create more software, faster, easier, and cheaper. The rules of basic economics apply: by making software development faster, easier, and cheaper, you get get more software developed. They are the Big Bang from which the SaaS universe has expanded to infinity.

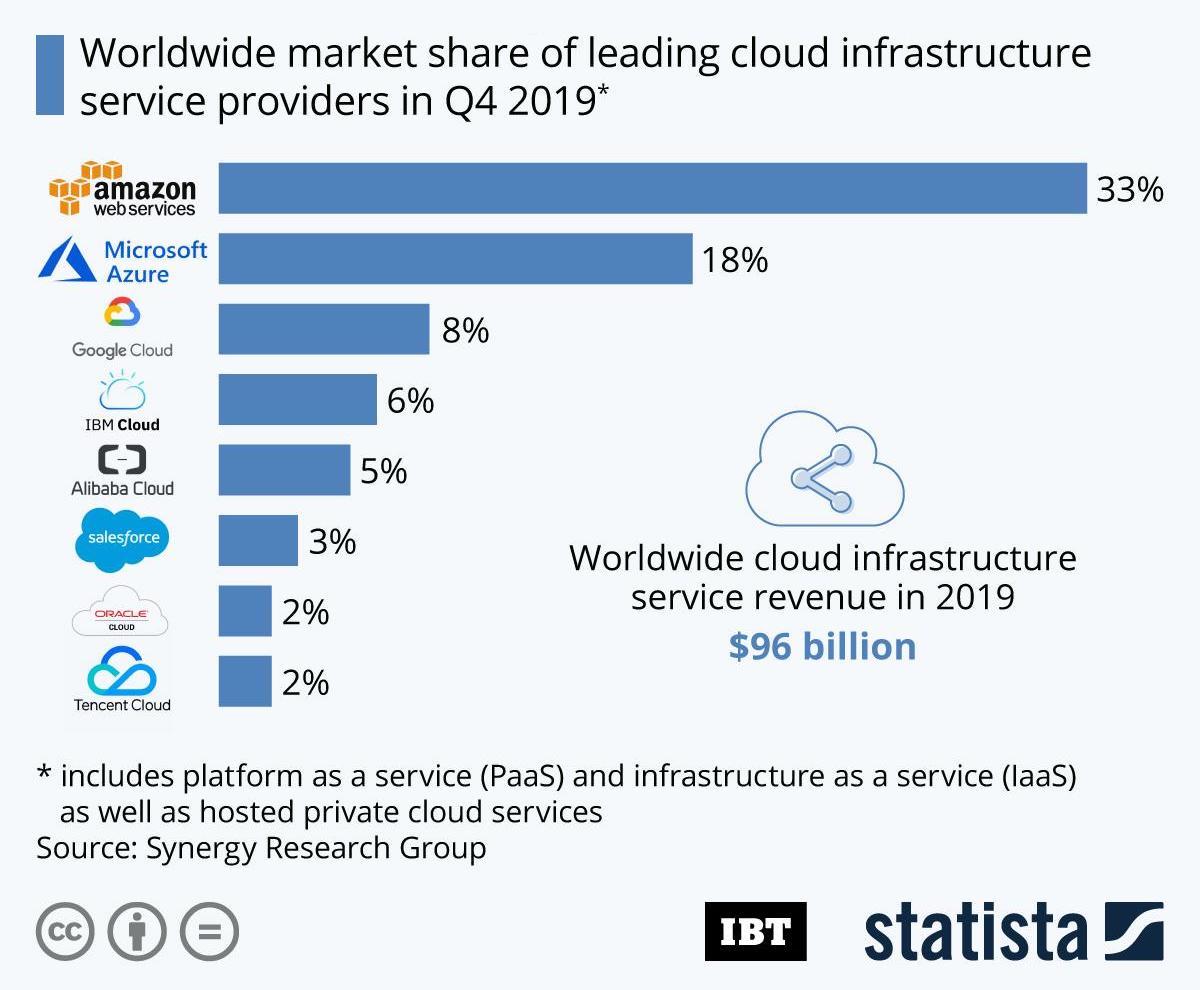

- They’re extremely consolidated. Amazon, Microsoft, Google, IBM, and Alibaba dominate with 70% of total market share between them. AWS leads with a whopping 33% market share — 1/3 of everything in the cloud runs on their platform. It’s going to be very hard for a new player to break into this oligopoly.

From that cloud platform foundation, we go up the spectrum to higher-level and more specific software technology, with each layer enabling others above it to stand on their shoulders:

- Service Platforms: built on top of cloud platforms, service platforms offer higher-level capabilities to developers. Two canonical examples are Twilio and Stripe, for telephony and payment processing services respectively. They too are highly extensible — in the business of empowering app builders — but more narrowly so, around their specialized service. There are more of these firms, but they are still relatively consolidated.

- App Platforms: built on a combination of cloud and service platforms, app platforms are the layer that starts directly serving business users. Salesforce is the original example, but now there are hundreds, of varying sizes, serving different functions and verticals: Shopify, ServiceNow, HubSpot (disclosure: where I work), Adobe, Intuit, Xero, Atlassian, Google’s G Suite, MindBody, and many more. They’re “platforms” because they’re extensible, with other app businesses built around them. They tend to consolidate within their domain.

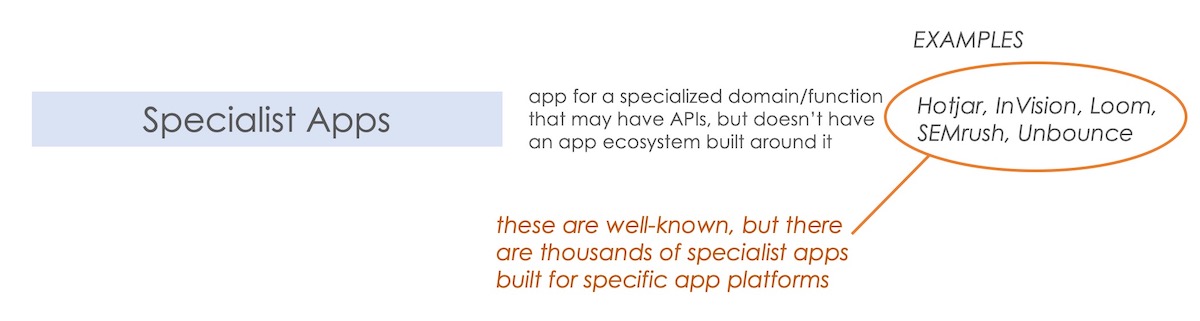

- Specialist Apps: any other cloud-based app that is packaged as a product for others to use is a specialist app. That’s not a knock on its value. There are specialist apps worth billions of dollars, undisputed leaders in their field. They might be extensible with APIs, but they don’t have other app businesses built on top of their extensibility. There are thousands of them, ranging from unicorns such as InVision to a developer’s side-hustle creating a plugin for WordPress. Not all specialist apps are built around app platforms, although many are. Due to effectively zero barriers to entry for new apps, the total number of specialist apps in the world collectively does not shrink. Witness the Martech 5000. Yes, specialist apps beat others to achieve local consolidation. But new specialist apps keep being born.

- Custom Apps: any other cloud-based app that isn’t packaged as a product for others to use is a custom app. They’re built solely for a particular business — on the far end of the spectrum for business-specific logic. They might be extensible with APIs — generally a good practice in software these days — but only for the benefit of others in the company or their own partners and customers upstream and downstream in the value chain. There are millions of these apps — and millions more will be created in the decade ahead.

Is It an App or a Platform?

The word “platform” is highly overloaded. Many software products are called platforms these days. If you simply mean they are extensible or they are a factory for generating specialized assets — e.g., a landing page creation platform — that’s a perfectly fine use of the word.

However, in the spectrum of SaaS platforms and apps described here, the word “platform” has a concrete, quantifiable meaning:

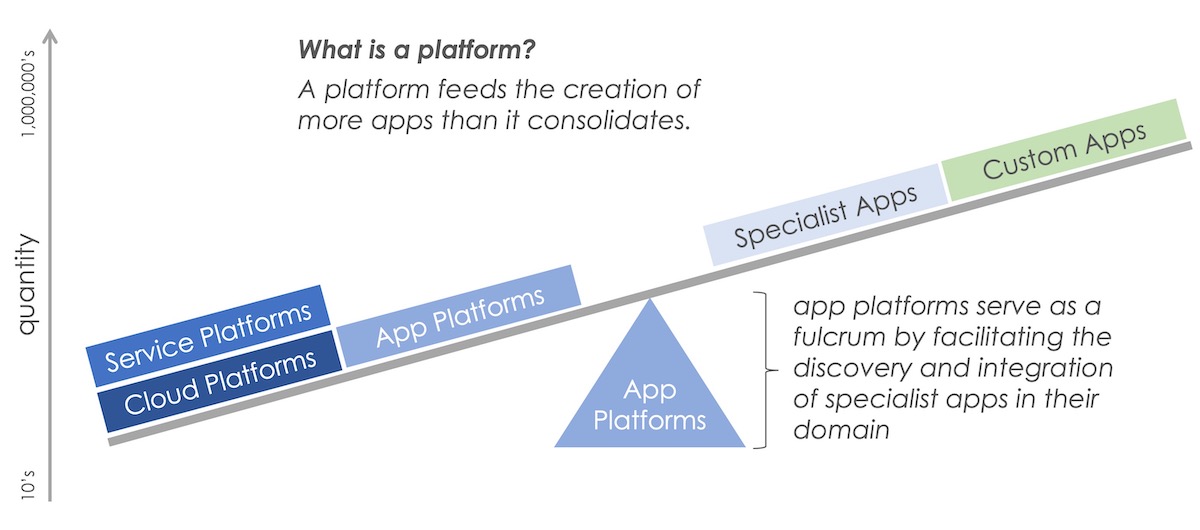

A platform feeds the creation of more apps than it absorbs through consolidation.

In the see-saw illustration above, platforms are low on the left side of the fulcrum, where consolidation dominates, while apps are high on the right side, lifted into large quantities by those platforms that have enabled them.

The “paradox” of consolidation and expansion, in martech and in SaaS more generally, is then simply explained by math: platforms consolidate while spawning more apps than they remove. The net number of apps in the world grows, even while there is intense competition driving consolidation further down in the spectrum.

One of the key ways platforms compete with each other? By fighting to enable more apps than their competitors. Think about that:

The more intense the competition is between platforms, driving their own consolidation, the more apps they help to create (in the layers above).

Greater platform consolidation = greater app expansion.

Cloud platforms and service platforms leverage app creation the most. That is their whole raison d’être. However, app platforms play a special role by facilitating the discovery and integration of apps within their particular domain. With so many apps in the world, that’s a highly valuable function to enable businesses to effectively harness the power of all these apps.

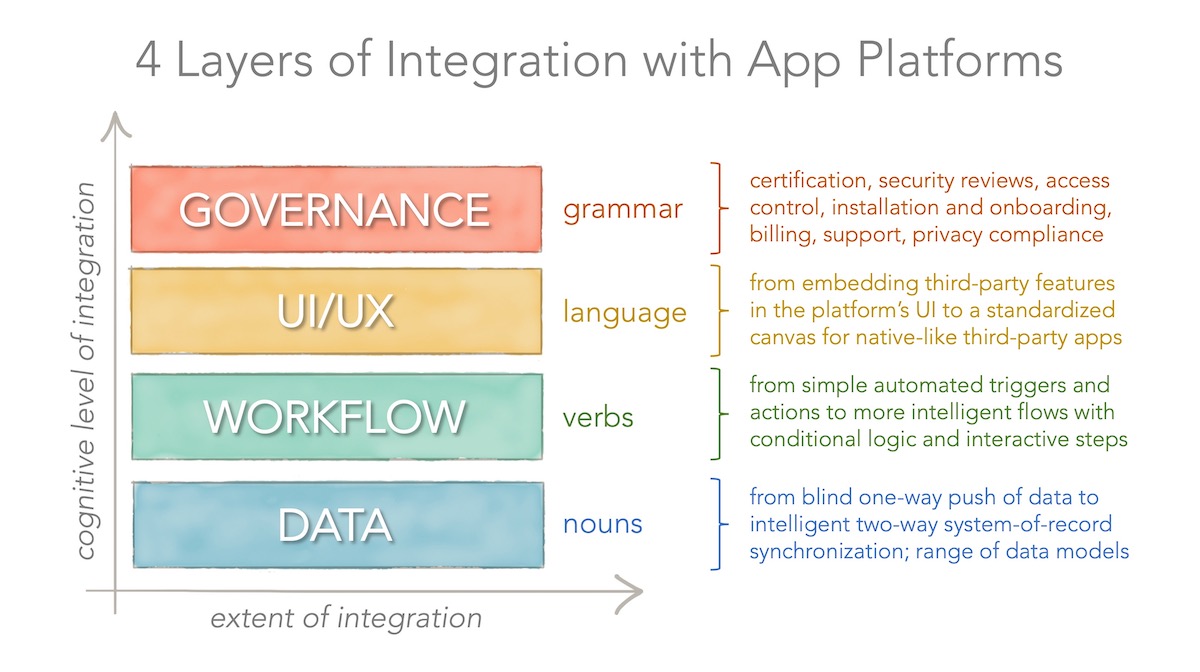

The 4 layers of app platform integration that I mapped out last year describes how an app platform can create cohesion within its ecosystem — making it easier for platform users to harness the innovation of a wide variety of specialist apps.

Again, the laws of economics apply: by making it easier for platform users to adopt specialist apps and unlock value from them, they adopt more of them. In turn, this incentivizes more entrepreneurs to create more specialist apps.

While there are eventually diminishing returns in new app creation, most app platforms today are still early in their evolution. As their app discovery and integration capabilities advance, I expect there will be room for many more apps within many of these ecosystems.

Key Dynamics of Apps and Platforms Crossing the Spectrum

What makes things interesting is that positions within this spectrum are not necessarily fixed. Cloud platforms go up to offer more specialized services and capture more value-add. (At the lowest layer, the general-purpose infrastructure of cloud platforms is often commoditized.) You can observe this push upward by browsing the hundreds of services that AWS now offers.

In fact, cloud platforms and service platforms may continue rising into the app platform layer. You can somewhat see this with solutions such as Amazon AppFlow and Amazon Pinpoint.

However, there tends to be a “domain chasm” between cloud/service platforms and app platforms that is challenging to cross in either direction. The main divide in this chasm is that cloud/service platforms serve developers as their primary audience, whereas app platforms serve business users as theirs.

This difference affects everything: brand, business model, pricing and packaging, marketing and sales, education and enablement, and the very experience of using the platform itself.

It’s hard to serve both markets well — although not impossible. Hybrid technical/business ops and IT professionals, such as our beloved marketing technologists, can help span these two segments of the spectrum.

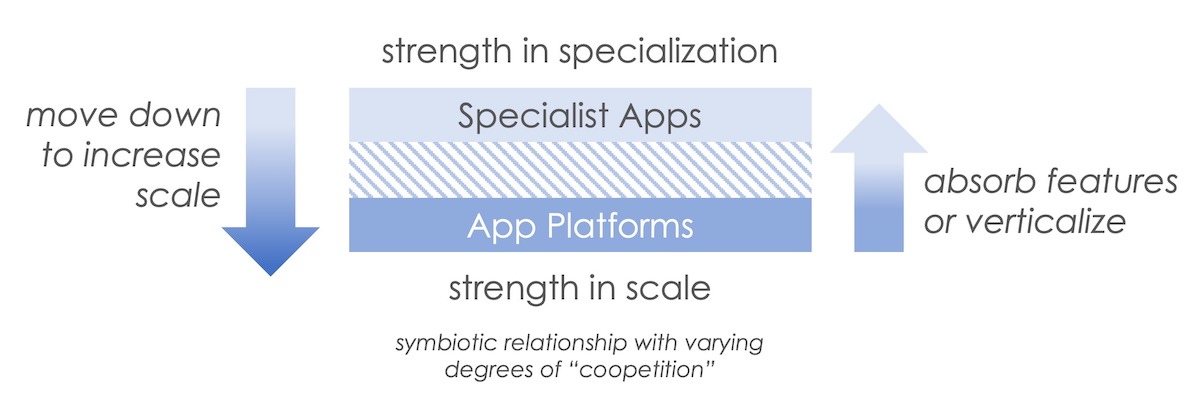

Where we more regularly hear of cross-spectrum competition and consolidation is between specialist apps and app platforms.

Relationships between app platforms and most of the specialist apps in their ecosystem are usually complementary and mutually beneficial. They have to be in order for an app platform to be successful as a platform. (See How to Build a SaaS Platform Third-Party Developers Will Love.)

However, it’s not uncommon to have some degree of “coopetition” in a platform ecosystem. Successful specialist apps, especially in later stages of their growth, may expand to become platforms themselves to increase their scale. And in the other direction, app platforms tend to absorb some specialist app capabilities over time, either through acquisition or simply the organic evolution of their own products to keep pace with customer expectations.

The lines can get blurry, as we certainly see in the martech space. A specialist app in one app platform’s domain might be a full app platform of its own in a different domain. And, yes, you can have app platforms built on top of other app platforms. (I think Douglas Hofstadter would appreciate that imagery.)

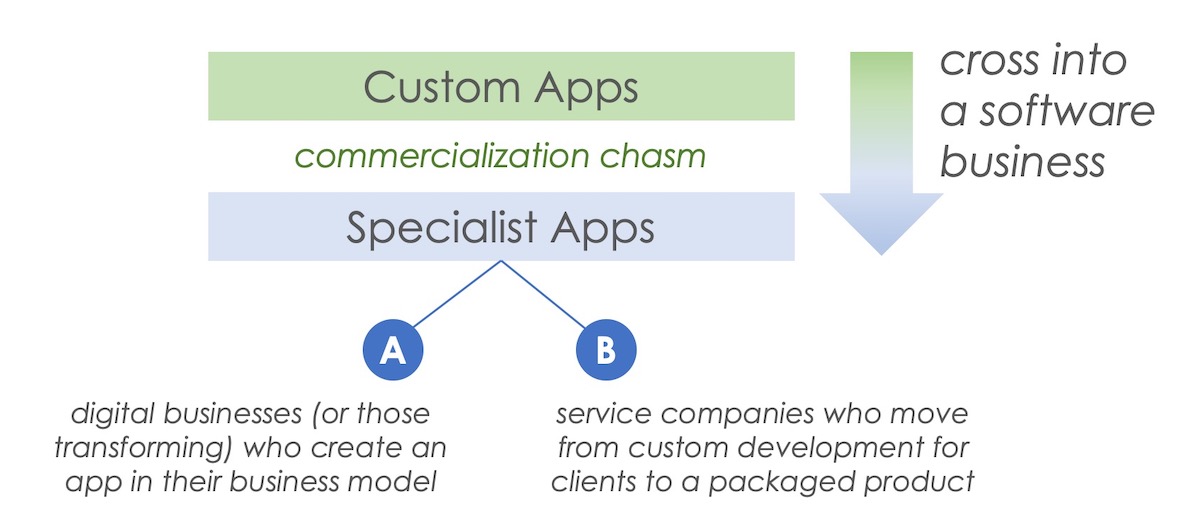

The cross-spectrum shift I see happening most frequently, however, is the migration of custom apps — built for one company’s own use — into packaged specialist apps that are then sold to others. There are two main flavors of this:

- New Digital Business: as part of a digital transformation (or just being born digital), a company may find that software it has developed could be valuable to either its existing customers or, more often, to serve an adjacent set of new customers. They package their software and start selling it, usually in its own business unit. For example: Arity, a mobility data and analytics software venture launched by Allstate.

- Services-and-Software Businesses: a professional services company seeks to bottle their “secret sauce” into software or, if they develop custom apps for clients, they might identify a repeatable pattern across many clients. They decide to launch an app as a product from their expertise and experience — possibly as a stand-alone profit center, but often as a client acquisition/retention strategy or simply a way to deliver their services with greater efficiency and value-add differentiation. This is the blending of software and services that I described in Second Golden Age of Martech.

Turning a custom app into a specialist app business is not easy. It’s a different business model, often with very different operational dynamics than the original business that created it. I’ve labeled this as a “commercialization chasm” that shouldn’t be traversed lightly.

So why does this shift happen so frequently? It’s the result of a huge pool of millions of custom apps. Even if only a small fraction attempt commercialization and the probabilities of success are low, the absolute number of specialist apps being launched through this process is large.

As the world becomes more and more digital — “digital transformation,” buzzword that it is, is still early in its journey — these leaps from custom apps to packaged specialist apps will only increase. I expect by orders of magnitude over the decade ahead.

The Platform/App Spectrum Is a Long Tail

To close this full circle, we can map this app/platform spectrum to the long tail graph that I’ve drawn many times before to show the distribution of scale across the martech landscape. Two truths clearly co-exist in martech and SaaS in general:

- There is massive consolidation in platforms.

- There is massive expansion and diversification in apps.

It’s not a paradox. It’s the very structure of business in the cloud.

“Again, the laws of economics apply: by making it easier for platform users to adopt specialist apps and unlock value from them, they adopt more of them. In turn, this incentivizes more entrepreneurs to create more specialist apps.”

That’s IF platforms put up economic and procedural barriers that prevent those entrepreneurs from delivering market-desired services.

You’re right. (I assume you mean if they *don’t* put up those barriers.)

You could write a whole book on good and bad practices of platform strategy and management between app platforms and specialist apps. (I probably shouldn’t have planted that idea in my head.) I think many app platforms wrestle with how to be a great platform, not just a great product.