15 years ago, sitting at a wobbly kitchenette table in our cramped apartment, on a frigid February morning outside Boston, I started this blog for marketing technologists.

Of course, at the time, almost nobody knew what a marketing technologist was. It sounded like an oxymoron. While there were certainly people already working at the intersection of IT and marketing, they were few and far between. Their roles were often ill-defined and underappreciated. But it was clear they were forging a future that was coming at us fast.

I related to them, as a strange hybrid with a non-traditional career myself. My parents had run a small ad agency, with my dad as an exacting copywriter. As a teenager, I developed — and marketed — multiplayer games for dial-up bulletin board systems (BBSes), a precursor to the Web. In the heyday of the dotcom boom and bust, I was the CTO of an agency building enterprise websites for marketing departments. And in 2005, I launched a SaaS product for marketers to build no-code (!!) landing pages and interactive content.

I lived with one foot in marketing, one foot in software engineering. And I loved it.

Today, there are 100,000’s of marketing technologists globally, thriving in careers that are celebrated and in high demand. It’s been a joy to have a front-row seat to the birth of this industry and the incredible evolution of marketing as we know it. I’m grateful and humbled to have been fortunate enough to play a part. I really do love this stuff.

So on this anniversary, I thought I’d share 15 reflections on martech and more that have stuck with me on this journey.

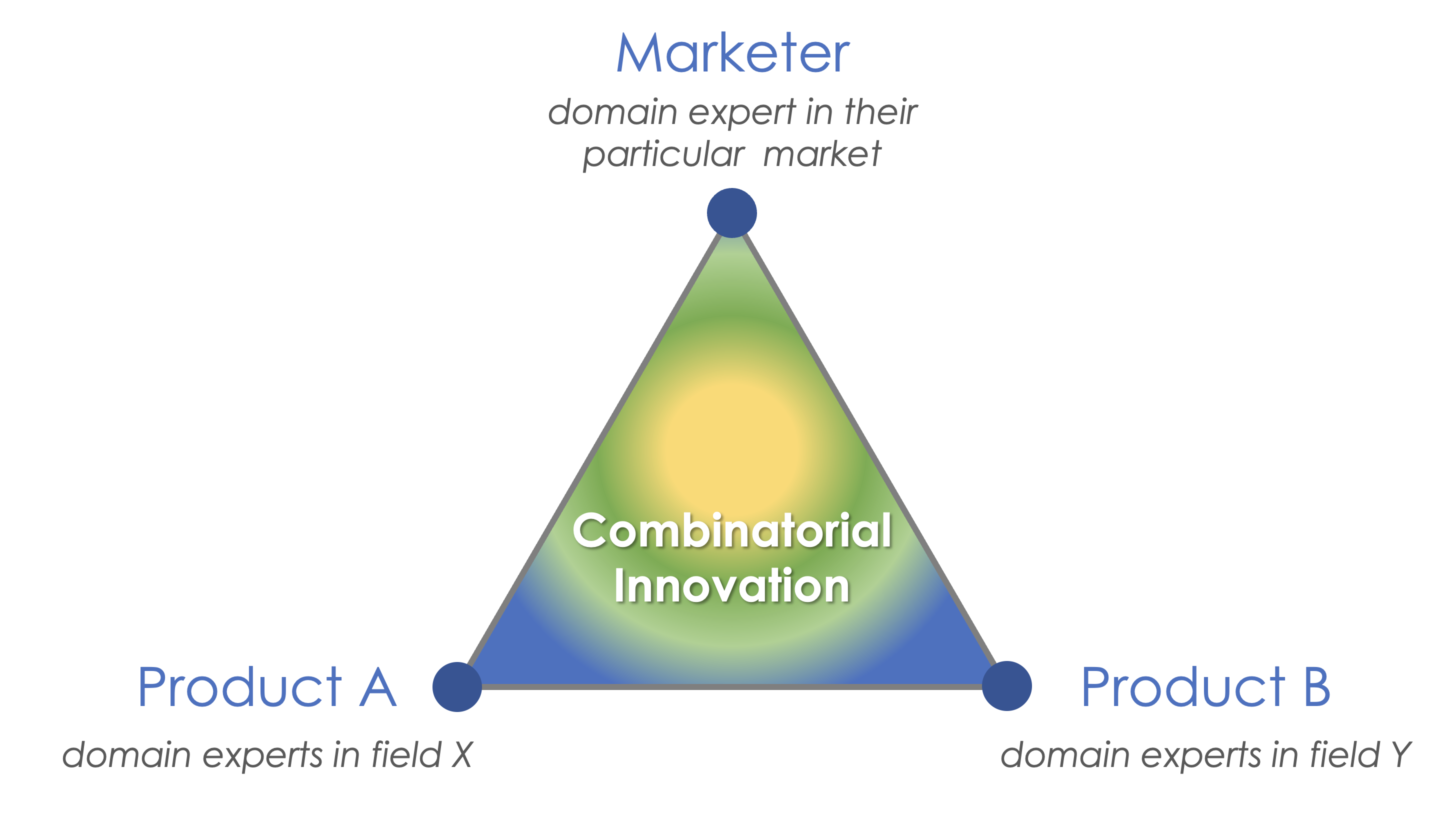

1. Intersections between fields are gold mines.

There’s value in deep expertise and specialization, for sure. But intersections of different disciplines are abundant in opportunities to cross-pollinate concepts and capabilities. Seek out opportunities to mix and mingle with professionals from other fields. Open your mind to blending ideas from hobbies and passion projects into your work. Combinatorial innovation unlocks infinite possibilities. Embrace the adjacent possible. (One of the most influential books I ever read on this dynamic was The Medici Effect by Frans Johansson.)

Hacking Marketing, my own book, was about the cross-pollinating ideas from managing software development to managing marketing. (The dedication to my daughter read, “Let your imagination always lift you beyond the limits of labels.”)

2. Heed the 10/90 Rule of technology and people.

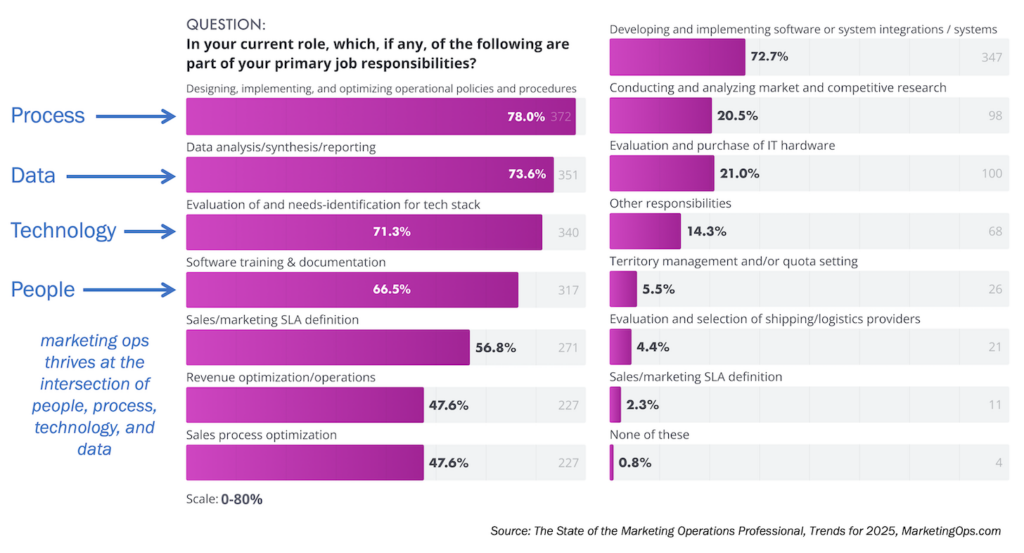

Web analytics guru Avanish Kaushik proposed the 10/90 Rule in 2006: to have magnificent success, for every $10 you invest in tools and technologies, invest $90 in people and their development for harnessing that tech.

While I am sometimes mistaken as a martech tool nut — well, okay, I kinda am — I’m an adamant believer in the 10/90 Rule for companies to succeed with marketing technology. If there’s a law of gravity for martech, this is it. And I’ve witnessed hundreds of cases where companies leapt off a tall tech stack disregarding that law, only to experience a Wile E. Coyote splat shortly thereafter. Invest more in talent than tools.

3. Code is creative. Full stop. (Actually: full start.)

In the Dark Ages of a couple decades ago, technologists were pegged on one end of the career spectrum and marketers at the polar opposite. A popular misconception in marketing was that code was a purely analytical craft. Programmers were not “creatives” in their eyes. (Programmers had their own opinion of marketers that wasn’t particularly flattering either.)

Of course, this was total baloney. Coding is a quintessential act of creation. A copywriter weaves words, but a coder can weave worlds.

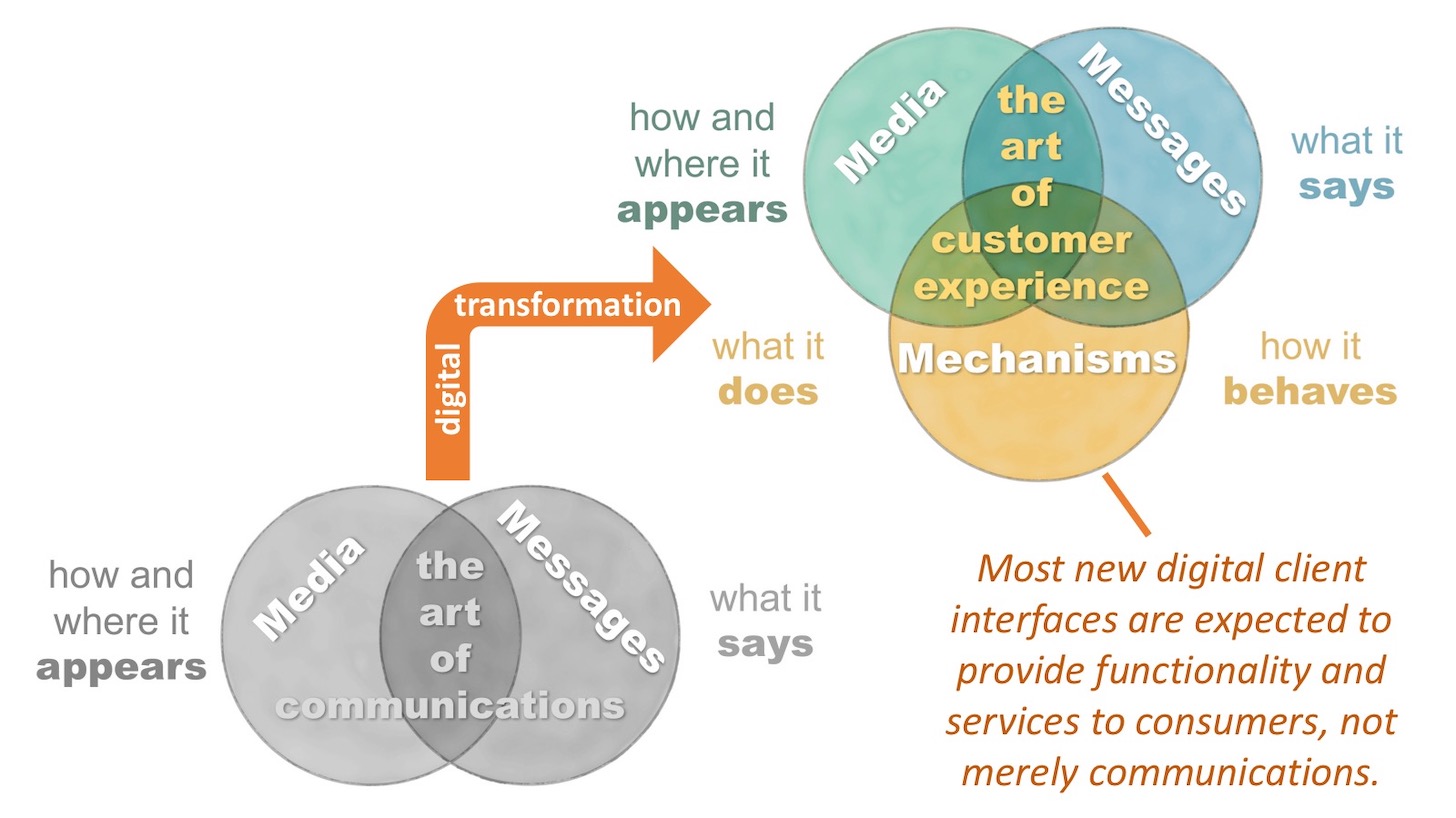

This is crucial to comprehend, because in the age of AI and no-code, marketers can increasingly wield the power of “code” themselves to create experiences. With huge leaps in martech innovation on the horizon, the range of experiences capable of being created is going to be breathtaking. (One of my more passionate posts was a 2016 letter to the editor of AdAge rebutting that “martech is so boring.”)

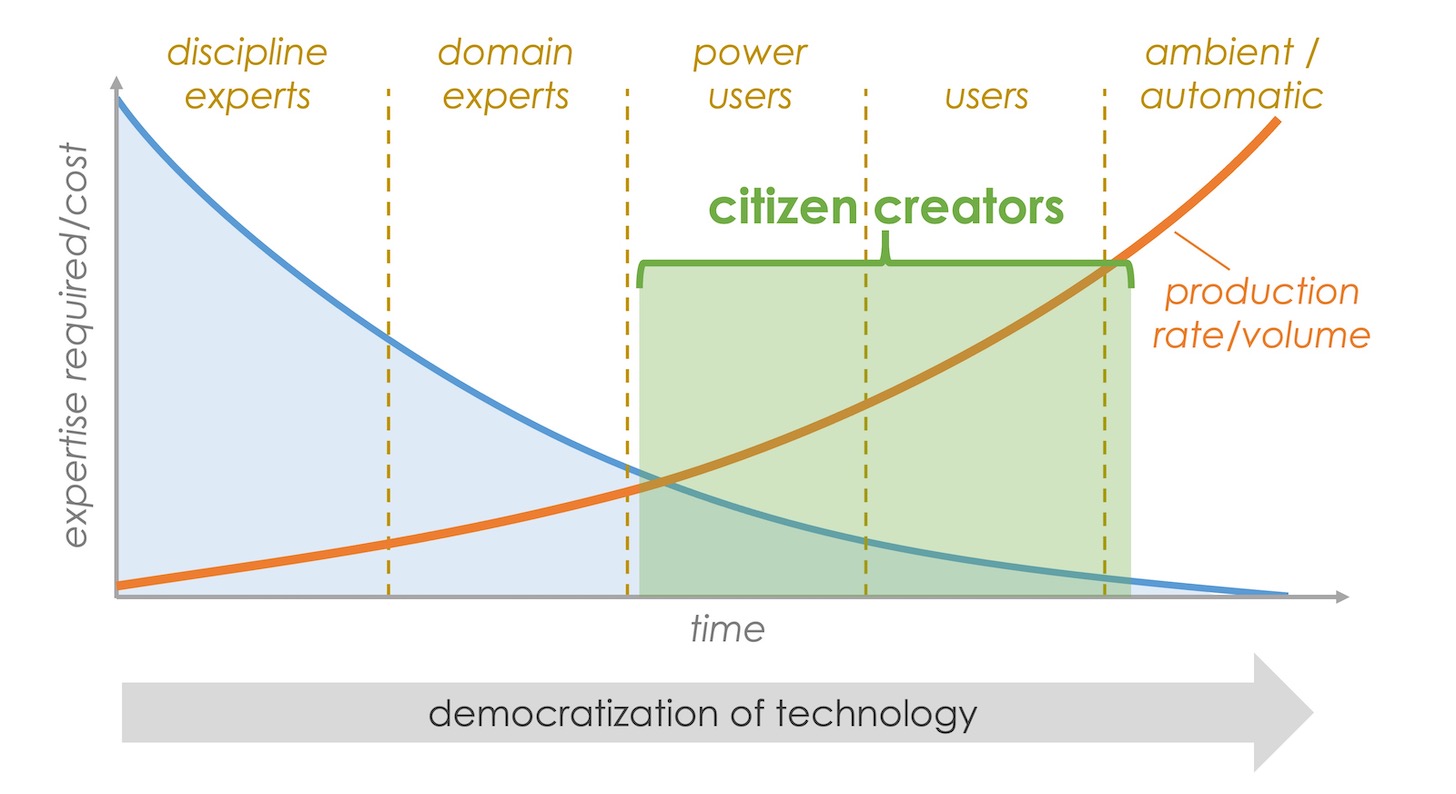

4. Technology trends towards democratization. Ride the waves.

Back in the 1970’s — when Elvis was still alive and touring — people scoffed at the notion of “personal computers.” In the age of mainframes and not-so-mini minicomputers, the idea of a computer in every home and on every desktop seemed ludicrous.

You’ve probably heard the anecdote that today, the smartphone you carry around in your jeans is 900 million times more powerful than Apollo 11’s guidance computer. It’s also approximately 5,000 times faster than the CRAY-2 supercomputer of the 1980’s.

Nearly every technology innovation follows this pattern. We’re seeing it today with no-code tools imbuing non-technical marketers with technical superpowers. For entrepreneurs and practitioners in a domain, such as marketing, great opportunities are consistently found at the points where a technology crosses a boundary from a smaller specialist group of users to a larger, more generalist one. And you can see them coming from a mile away.

5. Amara’s Law and outsmarting Hype Cycles.

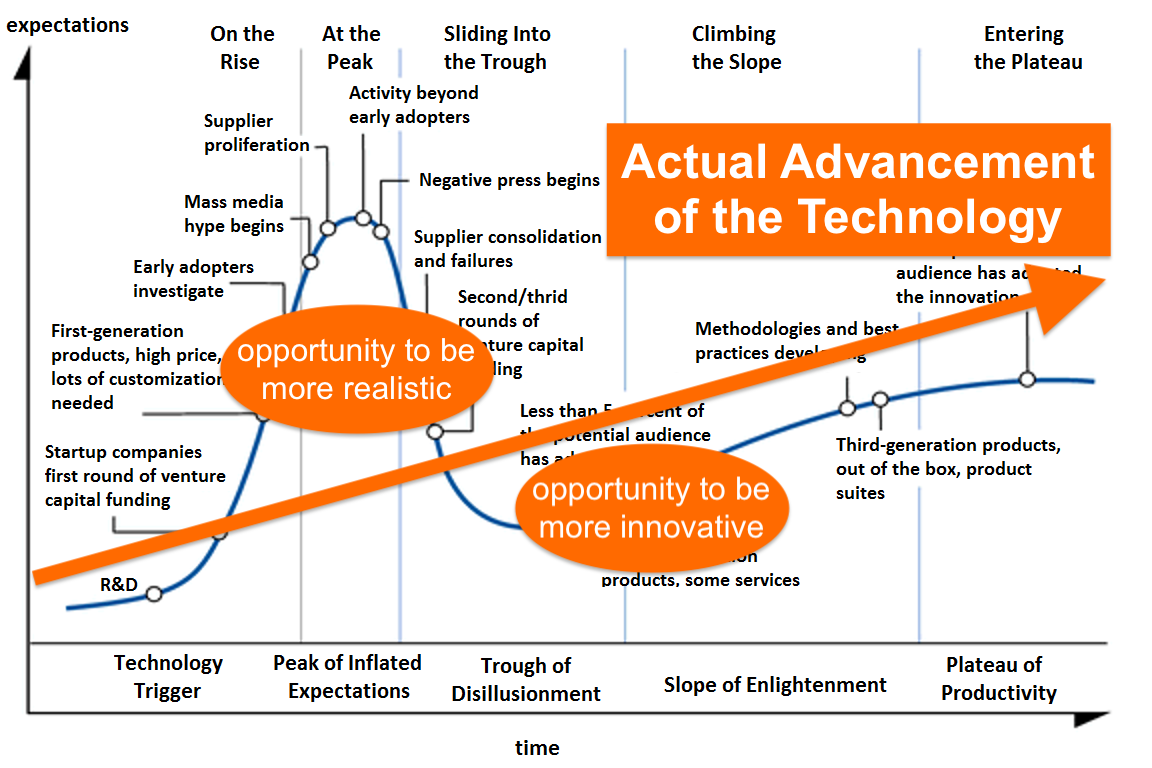

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” This observation made by Roy Amara in the 1960’s became known as Amara’s Law.

Ain’t that the truth. We’ve witnessed this with the Web, e-commerce, mobile, big data, AI. The whole of field of martech is a cornucopia of examples from the past two decades. The metaverse and Web3 are the most recent short-run overestimations that are also long-run underestimated.

Another way of framing this phenomenon is Gartner’s Hype Cycle. Overestimating in the short run gives us the Peak of Inflated Expectations — and then we tumble into the Trough of Disillusionment. In time, we find Enlightenment. But if we resisted our back-to-back overestimation and underestimation instincts, the trough wouldn’t be so deep.

I wrote in 2018 that seeing through this pattern gives you opportunities to “beat the market” in how and when you leverage new technology.

6. Empirical data vs. survey data. Survey says…

I read a dozen martech-related reports every week. The vast majority of them rest on data that was collected from surveys. But as interesting as I find many of these studies, they often suffer from two flaws: (1) the answers people give are inaccurate — feelings more than facts — and (2) the people who answered the survey are skewed by selection bias.

Example of inaccuracy: ask people how many tools they have in their tech stack and they will almost always report a number that is much, much lower than the real number they get when they use a SaaS management platform to inventory their actual tool count.

Example of selection bias: a CDP vendor runs a survey about CDPs, but the respondents are mostly their own customers; if a high percentage report having implemented a CDP, that’s not representative of CDP adoption more broadly in the market.

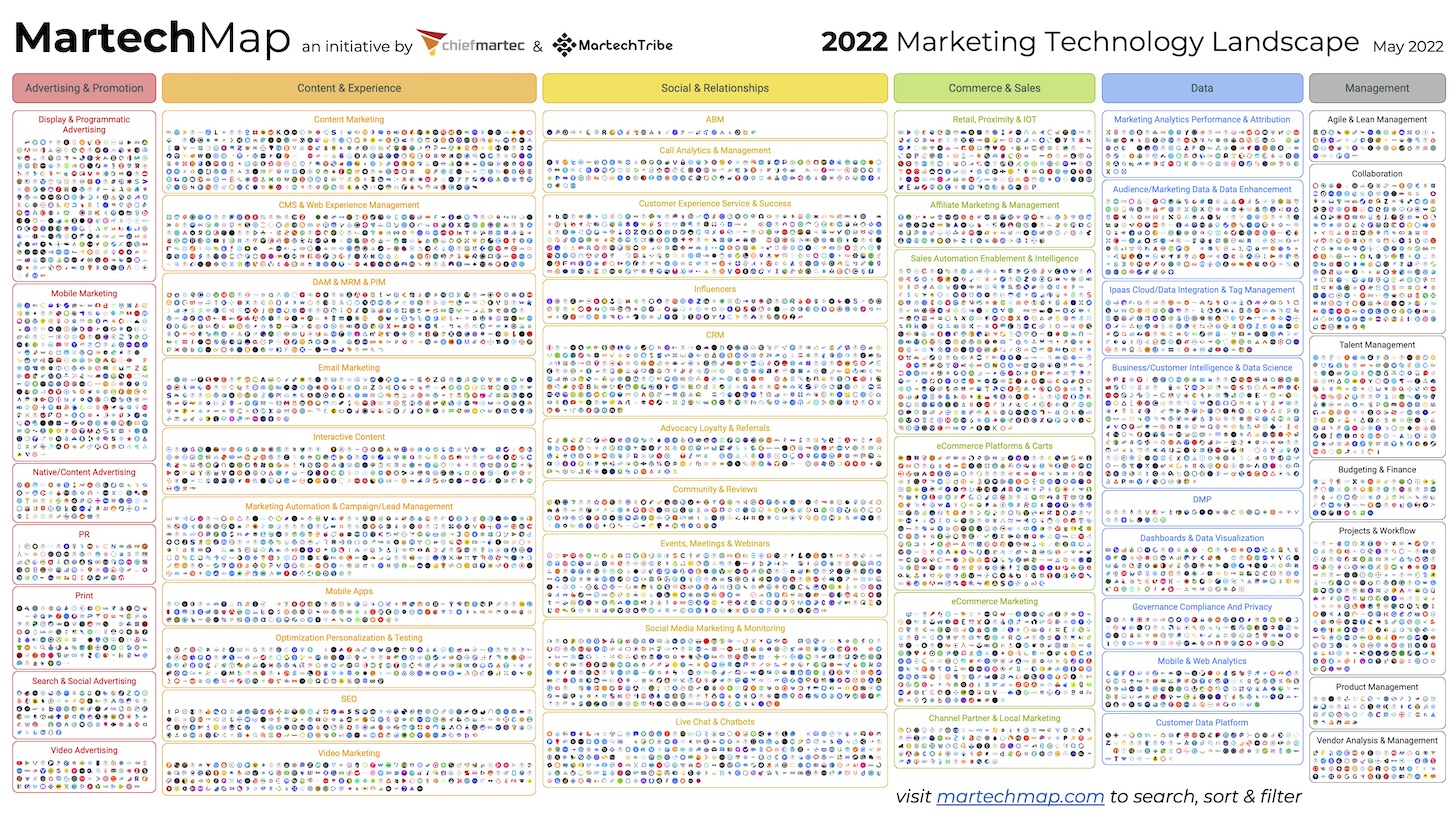

Empirical data is much more accurate, and its selection bias — where did the data come from? — is usually more transparent. Automations people build in Workato is empirical data. Number of software products in G2 is empirical data. The martech landscape, year over year, is empirical data too.

Survey data reveals what people think. Empirical data reveals what people do.

7. The right picture is worth a thousand logos words.

The most surprising thing to me about the martech landscape has been its… well, crikey, its exponential growth! But the second most surprising thing to me has been how widely this hot mess of a logo casserole has traveled and how many people it’s influenced.

The biggest learning it’s given me — other than the triumph of empirical data over wild conjecture (e.g., people in 2014 claiming the ~1,000 mapped solutions would collapse within a couple of years; spoiler alert: that didn’t happen) — has been to appreciate how influential the right visualization can be in illuminating a complex subject.

Standard charts and graphs are useful and serve a purpose. But novel visualizations can help us see things in a very different way. My advice: sketch more, draw outside the lines.

8. Respect the “crazy ones” building in the trenches.

I don’t mind critics of the martech landscape. But it does bother me when people dismiss the entrepreneurs building these martech ventures. “All these products do the same thing.” No, actually, they don’t. Just because those critics can’t imagine how martech could be improved or innovated — even if only incrementally — doesn’t mean others can’t.

Now, most entrepreneurial ventures fail — in martech as much as any other field. So in a purely statistical sense, those cynics can justify their claims. But many of those ventures do succeed — some fantastically so — pushing the frontier of marketing forward. And in a very real sense, those winners emerge only through the crucible of continuous competition.

But beyond that, show a little respect for the people who are pouring their passion into building something. The odds are against them, but they have the courage to jump in the arena. The people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.

9. Antifragility — things that grow stronger with change.

Possibly the single most influential book on my thinking has been Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Fragile things are harmed by shocks and stressors. Robust things withstand them. Antifragile things actually get stronger.

Go ahead, make a joke about the martech landscape guy appreciating disorder.

But in all seriousness, the martech landscape is an excellent example of an antifragile system. Collectively, all these martech vendors competing with each other, responding to emerging technologies and changes in consumer preferences and behaviors, make the entire martech industry stronger over time. Individual companies will falter, but they’ll be superseded by evolutionarily “better” ones.

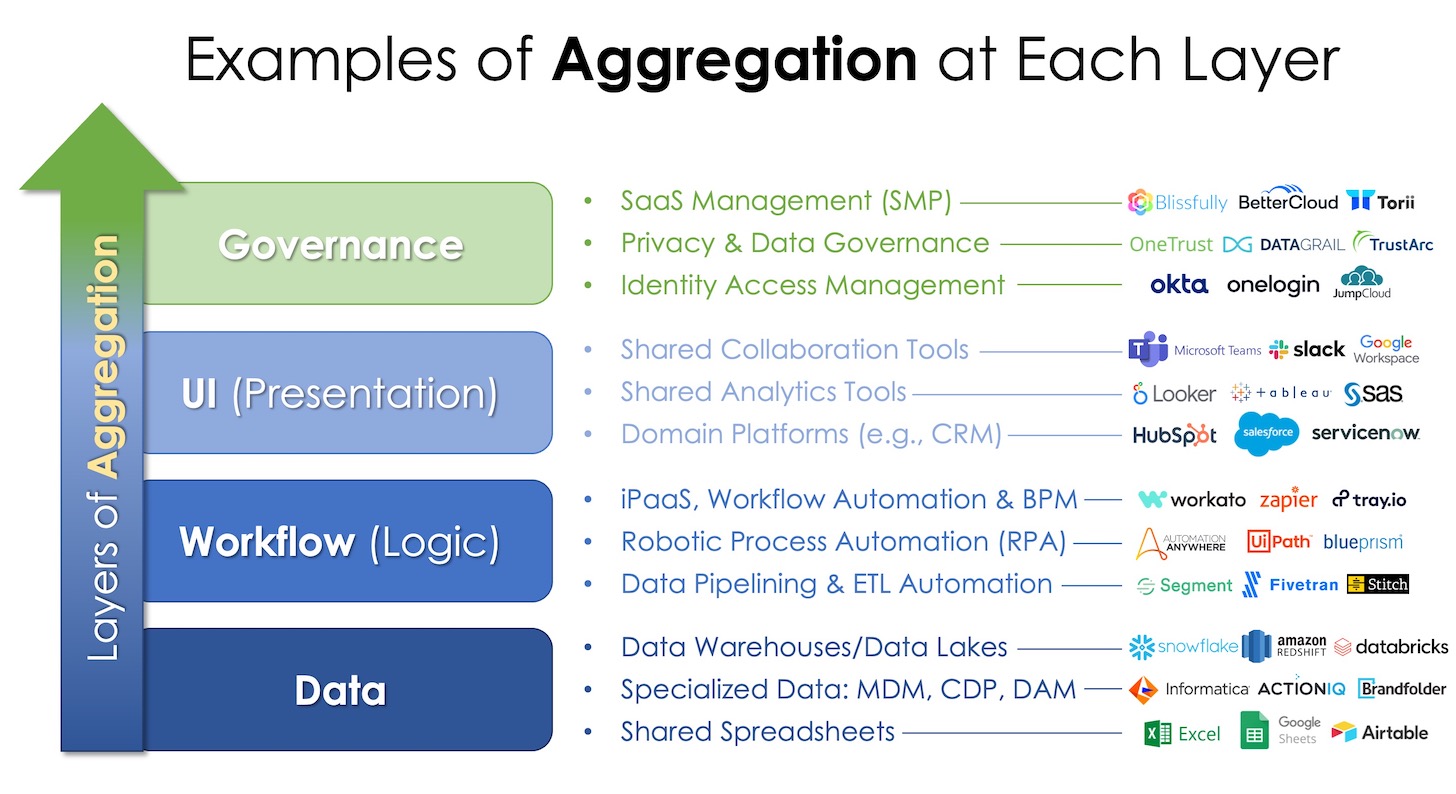

Open platform ecosystems are also antifragile for the same reason, as microcosms of a larger industry. Any one software company can only build so many things, in their own “opinionated” way. Ecosystems enable many different “opinions” to be expressed across a much wider range of capabilities. The ecosystem overall adapts to changes and different use cases at a remarkable pace, growing stronger as a result.

Even your own martech stack can be antifragile, if you design it using platform principles to adapt and grow stronger with ever changing apps, data, and use cases.

10. Conway’s Law and (my proposed) Inverse Conway’s Law.

Conway’s Law states that organizations design systems that mirror the organization’s communication structure. If three teams build a product, the product will probably have three distinct pieces.

More broadly, a software company will produce a product that reflects not only its internal team structure, but also its culture and philosophy. This is often referred to as “opinionated” software. That can be a good thing — if you like their culture and philosophy.

It’s one of the reasons I advise martech buyers to evaluate not only a vendor’s functionality and pricing, but also the behavior of the humans they interact with there. Their attitudes. Their ideas. The ways they communicate. This will be reflected in their software and the experience you have with it.

This is important because when we adopt a major software platform, we often adapt the way our company works to leverage it properly. I call this Inverse Conway’s Law: your organization’s communications structure will evolve to reflect the design of the systems you implement. Choose wisely.

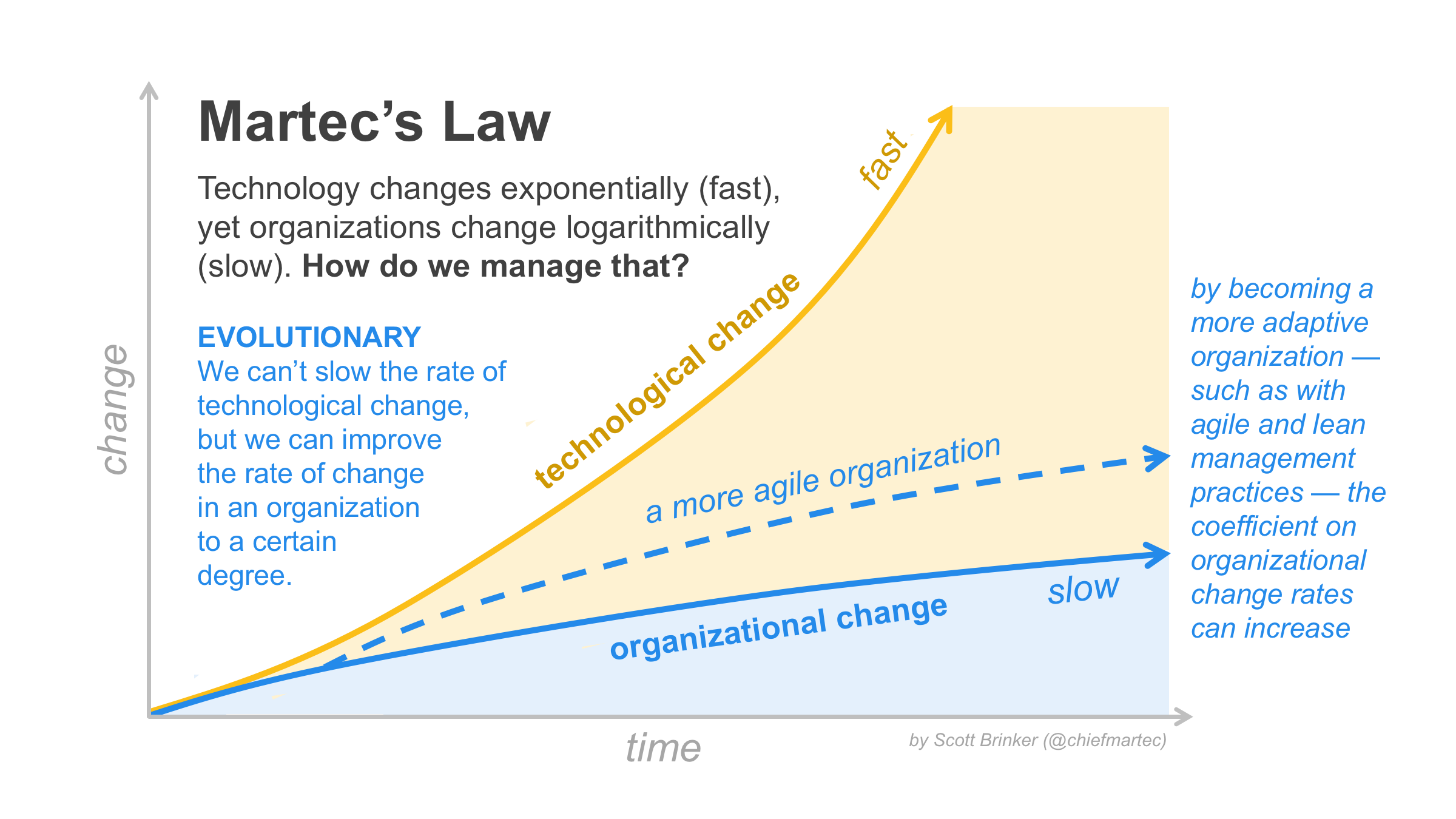

11. Martec’s Law: you are the change you choose.

If there’s any “law” that I’m associated with though, it’s Martec’s Law: technology changes exponentially, organizations change logarithmically.

Coined in 2013, it’s not a law in any scientific (or legal!) sense, but a general observation. The greatest management challenge of the 21st century is navigating an organization through the rushing rapids of technological change. We can’t keep up with all of it. So we have to be intentional and strategic about which changes we embrace — and which we don’t. Developing organizational agility (and architectural antifragility) is a tremendous competitive advantage in this environment. It lets you change faster than your rivals.

The pandemic revealed there are sometimes opportunities to make a step-function leap in organizational change. Not easy, but the occasional “reset” in a company can be a powerful way to renew. (As the adage goes, “Never let a crisis go to waste.”)

As an interesting aside, apparently Martec’s Law influenced the Portuguese navy.

12. A sense of humor is a competitive advantage too.

Wrangling Martec’s Law, day in, day out, isn’t easy. Constant change can be a fascinating life of adventure. But it can also be stressful and exhausting.

One antidote I turn to is humor. The occasional indulgence in silly dad jokes (2020, 2021). Playful April Fool’s posts, such as my Microsoft acquisition, the unveiling of hyperagile marketing, or the ultimate consolidation of the martech industry. And even a bit of satire with more bite.

I’m not saying I’m any good at it. In fact, be warned, those dad jokes are truly terrible. But finding ways to bring some levity to all the serious work we do makes the journey more fun. And I believe we do our best work when we’re having fun.

It’s one of the reasons I am a huge fan of Tom Fishburne and his weekly Marketoonist strip.

13. Good artists borrow, great artists steal.

“Good artists borrow, great artists steal” is attributed to Pablo Picasso. Now, to be clear, I’m not advocating for plagiarism or copyright infringement. (Looking at you and your friends, dear DALL-E.)

But voraciously devouring smart thinking and creative ideas wherever you can find them, being inspired by them, and — with proper attribution — building on top of them is the best way to make progress. It’s the antithesis of “not invented here.” Stand on the shoulders of giants. And thank them for the lift.

Brian Solis’s Conversation Prism mapping social media and Terence Kawaja’s original adtech LUMAscape were key inspirations for the first martech landscape I created. A value chain model taught to me by Ducan Simester, my marketing professor at MIT, gave me a framework for evaluating horizontal vs. vertical competition in martech.

More recently, my view of aggregation dynamics within martech stacks adapts Aggregation Theory as defined by Ben Thompson of Stratechery.

14. Bias for action. Just do it. Ship an MVP.

Possibly the best career advice I got was from my discrete math professor: do something.

He was talking about strategies for making it through his notoriously hard exams. But really, he was talking about strategies for life. We rarely have a perfect plan with a guaranteed outcome in our line of sight. Waiting for one can leave you waiting forever. Doing something — anything — is often the catalyst we need to start a snowball rolling down the mountain.

This same advice has been repeated millions of times, in millions of variations. Just do it. Ship an MVP. Fortune favors the bold. A bias for action. Do or do not. The journey of 1,000 miles begins with a single step.

On that cold February morning 15 years ago, I could never have imagined the journey I would take with this blog. Along the way, I’ve tried hundreds of ideas — most of which fizzled or fell flat. But a few took flight. Like competition in the vast martech landscape, the ones that succeeded only emerged through the jostling of the many more that didn’t.

Have an idea? Not sure where to start? Do something, anything, and see where it leads.

15. Be grateful and pay it forward.

If we occasionally stand on the shoulders of giants, we continually lean on the shoulders of many friends, family, co-workers, teachers, advisors, community members, and even the kindness of strangers. This wondrous web of people in our lives is an incredible gift.

It would be impossible for me to thank everyone who has contributed to my long martech journey. You, dear reader, are one. But a few people I must absolutely call out: Chris Elwell for launching the MarTech Conference with me. Anand Thaker, Jeff Eckman, and Frans Riemersma for their collaboration on the martech landscape. Brian Halligan and Dharmesh Shah for letting me help shape HubSpot’s martech ecosystem. And super early advocates Jon Miller, Mayur Gupta, Jill Rowley, Laura McLellan, Gord Hotchkiss, Sheldon Montiero, Erica Seidel, David Edelman, Rishi Dave, Brian Kardon, David Raab, Jascha Kaykas-Wolff, Christopher Penn, Paul Roetzer, Ann Handley, Doug Kessler, and the late Wilson Raj.

Thank you.

One of the best ways to express gratitude to all of the generous people who have helped you: pay it forward. I’ll do the best I can.

Here’s to the next 15 years.